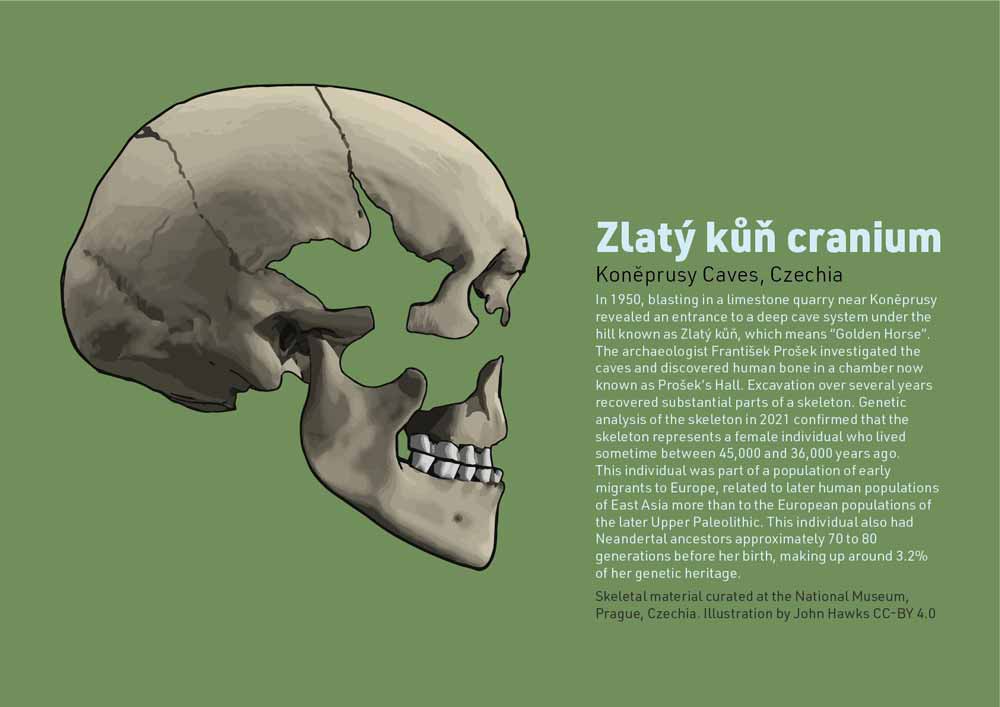

Fossil profile: Zlatý kůň and the Neandertal heritage of early Upper Paleolithic Europeans

A skull from Czechia represents an individual from one of the earliest European modern human populations to encounter Neandertals.

Two papers came out earlier this year showing relatively recent Neandertal ancestry within the genomes of early Upper Paleolithic Europeans. The paper about Bacho Kiro, Bulgaria, got more attention. The Neandertal connection was more recent (within 6 generations) and the journal more prominent. But I am more focused on the analysis of the genome from the Zlatý kůň skeleton. The history of thinking about this partial skeleton, and the way this paper changes that thinking, has much to reveal about this moment in the science.

The Zlatý kůň skeleton was discovered in 1950 in Czechia when a nearby limestone quarry blasted an opening into a previously unknown cave system. The skeletal remains and many artifacts were within a debris cone from a chimney going higher into the cave. From the beginning, it was unclear whether the skeleton and artifacts were associated. All appeared to have entered accidentally, falling from chambers above. This was not an occupation site. The human remains emerged over several excavation seasons. Svoboda, who summarized the context in a 2000 review, was very skeptical about the (few) artifacts: “Traditionally, rather than on the basis of any typological data, archaeologists ascribe these finds to the Early Upper Paleolithic.”

Anthropologists prior to 2000 who worked on Upper Paleolithic material from Central Europe, many my close friends, thought Zlatý kůň was very comparable in anatomy to Mladeč, a very early site. They placed Zlatý kůň within the sample of earliest Upper Paleolithic skeletal remains. Some suggested its occipital morphology might reflect Neandertal ancestry, and noted that its cranial morphology is relatively robust for a female adult individual, resembling other skeletal remains from this early Upper Paleolithic sample.

In the late 1990s, the scientific scene shifted. A new generation of scientists was starting to question these legacy sites from decades earlier, particularly in central Europe, using new radiocarbon approaches and other methods. A frontal bone from Hahnöfersand, Germany, once thought to be early Upper Paleolithic and a possible Neandertal hybrid, turned out to be only 5400 years old. A frontal fragment from Velika Pećina, Croatia, was Neolithic, not early UP. Human remains from Vogelherd cave, Germany, were thought to be Aurignacian in age, turned out to be Neolithic also.

Zlatý kůň was part of this redating regime, and Svoboda and coworkers in 2002 found a date: 12,870±70 years. They argued it was Magdalenian. In their paper describing the date, they wrote: “The region of the Bohemian karst has a predominantly Magdalenian occupation. No significant Early Upper Paleolithic site has been proved before in the vicinity.”

I’m going to some effort on this background because the redating wave at the turn of the century looked to many observers like science triumphing over cloudy-headed thinking. The past was not what anthropologists had thought! This was, of course, true to some degree. Yet today we get a sense of the overreach. The Zlatý kůň woman did not live 12,000 years ago; the radiocarbon assessment in 2002 was wrong, glue has contaminated the collagen content, and she lived at least 36,000 years ago and probably longer.

The DNA confirms some of what anthropologists thought 25 years ago, and adds the new resolution about a higher degree of Neandertal ancestry than today’s Europeans, with some Neandertal input within 70-80 generations of her birth. Also worth noting is the partial Neandertal ancestry in a chromosome 1 region that currently stands out as an “introgression desert” – the Neandertal ancestry hung around for some time in this region, compatible with drift or weak selection, not hybrid incompatibility.

It is probably no surprise to anybody that the current research doesn’t address the history going back to 1950 and ideas about where this skull fits into human relationships. This ancient woman has long mattered in the way that scientists constructed human identity. The two papers on Zlatý kůň and Bacho Kiro together presage a new shift in construction of early Upper Paleolithic identity. Their DNA seems to have made little difference to later populations in the European region, seems to reflect deeper and more eastern roots and relations. In this shift, we should be wary of overreach. These populations were a complex network. It will be amazing to find cultural connections with initial Upper Paleolithic in central Asia, at places like Kara-Bom. But biological connections may record a broader range of interactions. Today we are only scratching the surface of what the data hold, and simplifying to “closest” relationships, or quantifying relative Neandertal ancestry fractions, is not telling very much of the story that awaits us.

References

Hajdinjak, M. et al. (2021) Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03335-3 (Bacho Kiro)

Prüfer, K. et al. Nature Ecol. Evol. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01443-x (Zlatý kůň)

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.