How much Neandertal DNA do today's African peoples have?

New research shows that today's populations in Africa have around one third the Neandertal ancestry as people in Eurasia.

Note: This post is from 2020. This is a fast-moving area of science and the most current information may differ somewhat from the estimates in this post. In 2023, research by Daniel Harris and coworkers led by Sarah Tishkoff provided evidence from small samples of a wider array of African populations. They confirmed the evidence for Neandertal ancestry in populations from eastern and western Africa, and added observations from southern Africa with lower estimates of introgressed genome fraction.

In the wake of the initial Neandertal genome sequencing in 2010, journalists and many scientists spread the misconception that African people have no Neandertal genetic ancestry. That was wrong at the time and many people pointed out how wrong it was.

The research itself, from Svante Pääbo’s team, did not propagate this misconception. All of the authors were pretty consistent in noting that their tests could only measure the difference between sub-Saharan and other populations in Neandertal ancestry, and could not rule out Neandertal contributions to sub-Saharan African peoples.

Still, in the first year or two of genome-powered scientific conversation about Neandertal introgression, other scientists focused upon an alternative explanation: incomplete lineage sorting from a structured African population. As this idea was debated, again and again geneticists defended the introgression hypothesis by arguing that introgressed DNA was not found in Africa. As this genuine debate about incomplete lineage sorting was reported by journalists, they also reinforced the misconception that Neandertal introgression only exists in peoples outside Africa.

Through this period, I was one of the people working to debunk the myth that African populations have no Neandertal ancestry. A look at my 2010 post, “NEANDERTALS LIVE!”, shows me giving the correct answer for this question, “Do living Africans have Neandertal ancestry, too?”

The fact that living Africans are less genetically similar to the Neandertals is extremely important evidence of the Neandertals’ genetic contribution to populations outside Africa. But it doesn’t bear on how much back-migration into Africa may have happened.

We know that the answer is nonzero, because Africa has received immigrants from other parts of the world during historic times. The same genetic patterns that reflect population contacts up and down the East African coast, and across the Sahara into West Africa, show the possible conduits for the flow of Neandertal-derived genes into African populations.

I had actually grappled with this problem in my earlier paper (with Greg Cochran) in 2006, looking at what we should expect Neandertal introgression to look like: “Dynamics of Adaptive Introgression from Archaic to Modern Humans” (PDF). A number of scientists over the years suggested that any gene flow from Neandertals should be absent from Africans. That simply wasn’t true, and we pointed out why introgressed genes from Neandertals or other archaic humans might be found broadly across Africa.

Research over the last ten years has looked into the amount of Eurasian gene flow into Africa over the last 30,000 years, adding a good bit to our understanding of human population structure. That Eurasian gene flow was part of the big story of 2017, as early Holocene ancient DNA data from South Africa reinforced the finding that today’s southern African peoples have a good fraction of ancestry from Eurasian sources over the last 5000 years.

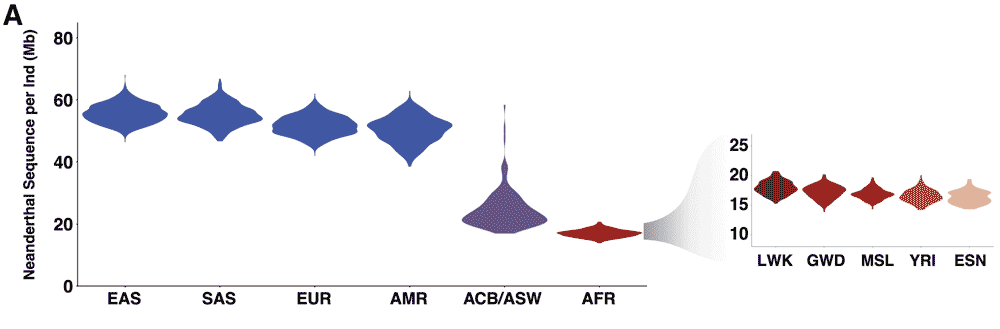

Earlier this year, Lu Chen and coworkers from Joshua Akey’s research group published an assessment of the amount of Neandertal ancestry in the genomes of present-day African people. Their paper provides some of the first accurate estimates that use the approach of identifying Neandertal haplotypes and looking for them in the genomes of living people. The results are sketched out in the following figure:

These comparisons are limited to 1000 Genomes Project samples, and those are mostly in the northern parts of sub-Saharan Africa, from Gambia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and Kenya. Chen and colleagues identify between 15 and 20 megabases of Neandertal DNA per genome in these samples. That’s around a third the amount that the authors find in Eurasian and Native American population samples. This method does not identify all introgressed segments: in the Eurasian population samples it seems to only pick up half or less of the fraction of introgression that has been estimated from D statistic approaches. So to estimate the total fraction of introgression in any given genome, it's necessary to incorporate this true positive rate. If European and Asian genomes have around 2% Neandertal ancestry, then these sub-Saharan African genomes have around 0.6%.

Based on their examination of the haplotypes, Chen and coworkers established that most of the Neandertal DNA in African populations comes from two sources. Some comes from so-called “back-migration” of Eurasian modern humans into Africa. That gene flow can mostly be traced to the last 50,000 years.

Such back-migration was not constant over time, and may have accelerated substantially during the Holocene. The population growth of the last few thousand years, with cattle pastoralism spreading southward across Africa, has helped fuel the spread of Eurasian genes in historic times. Yet a green Sahara during later parts of the Pleistocene also enabled contacts and dispersals that would have become more difficult in the recent, more arid North African landscape, so it will be interesting to weigh the changes over time in this gene flow.

The other source of Neanderthal DNA in Africa is incomplete lineage sorting of Neanderthal-African shared haplotypes that are absent in the rest of the world. Chen and coworkers look at the mutational differences among these and find that they have a peculiar age distribution. They do not date to the founding of the Neanderthal lineage more than 600,000 years ago. Instead, they are haplotypes that were transferred from African populations into Neanderthals by gene flow prior to 100,000 years ago.

Our own data are most consistent with models of human-to-Neanderthal gene flow between 100 and 150 ka, as IBDmix does not detect any signal in simulations with earlier gene flow. However, our results do not preclude earlier instances of gene flow, only that IBDmix is not powered to detect them. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that perhaps there were multiple waves of pre-OOA dispersals and admixture between modern humans and Neanderthals, although additional data are needed to make more definitive inferences.

Multiple waves of gene flow from Africa into Neandertals seem likely. Such intercontinental contacts are corroborated by fossil discoveries like those from Misliya and Apidima, both “modern-looking” cranial remains dating to periods before 150,000 years ago in Eurasia.

This paper has many additional interesting things to say about Neandertal introgression. The one that I want to mark before ending is that Chen and colleagues look back at the additional amount of Neandertal similarity in Asian genomes compared to European genomes. This “extra Neandertal” has been estimated in previous work to exceed 20% of the Neandertal ancestry of Europeans, meaning that East Asian people would have around 2.4% instead of 2.0% Neandertal ancestry. But that value assumed that Africans had no Neandertal ancestry. The Neandertal ancestry that does occur in Africa today comes in large part from gene flow out of western Eurasia, which means it is shared more with Europeans, Arabs, and other western Eurasian people than with East Asian populations. Looking at this effect, Chen and coworkers estimate that East Asian populations still have a bit more Neandertal than western Eurasian people, but only about half the previous bonus, around 8%.

It’s a cool paper that answers a number of worthwhile questions. It will be great to see larger samples applied to this and other similar problems. As I reflected in the Iceland Denisovan genetics post, we will learn much more when large samples can better characterize the haplotypes that have come from Neandertals and other populations.

I suspect when we have equivalently large samples in Africa, it will reveal a small amount of direct Neandertal introgression during the period of modern human emergence.

References

Chen, L., Wolf, A. B., Fu, W., Li, L., & Akey, J. M. (2020). Identifying and Interpreting Apparent Neanderthal Ancestry in African Individuals. Cell, 180(4), 677-687.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.012

Hawks, John & Cochran, Gregory. (2006). Dynamics of Adaptive Introgression from Archaic to Modern Humans. PaleoAnthropology, 2006, 101–115. http://www.paleoanthro.org/media/journal/content/PA20060101.pdf

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.