How capable were early human ancestors of crossing open water?

In past populations we should keep in mind the exceptional ability of humans to adapt to new circumstances.

Last summer I published a piece on Medium about the possible ancient existence of hominins on Luzon: “This is where scientists may find the next hobbits”.

For people who may not be familiar with this story yet, a study in Nature last year by Ingicco and colleagues reports on the butchered remains of an ancient rhinoceros from a place called Kalinga, on the island of Luzon. The bones have cutmarks and at least one percussion mark, and were found with some stone flakes, and one hammerstone. The remains are around 700,000 years old.

A reader asked me to dig back into the behavior issue:

I have a question for Prof Hawks. Given the recent discovery of hominin presence in the Philippines, do you think that paleoanthropologists have been underestimating the extent of behaviour possible by archaic humans as far as possibly Homo erectus?

The islands of Indonesia had very different geographic connections in the past. Java, Borneo, and Sumatra are large islands that were connected to the Asian mainland during periods when the sea level was 120 meters lower than today. That’s why they had (and still have) animals like rhinoceros, tigers, and orangutans that were also common in Southeast Asia.

Java, at least, also had Homo erectus populations starting as early as 1.5 million years ago, and lasting up to a half million years ago. We do not have evidence of any other hominins on Java at this time or earlier, but there is some good evidence now that the Homo floresiensis population may be a descendant of an earlier branch than even H. erectus. So maybe we’re talking about a hominin with an even more distant relationship to humans today.

The Philippines were never connected to the Asian mainland. The animal species there must all have crossed water at some point to get there. This was definitely possible for many non-human species, and the Philippines had both extinct forms like rhinoceroses and stegodonts, and surviving forms like tarsiers. All of them must at some point in the past have made one or more water crossings to get to these islands. The tarsiers have been there for more than 30 million years, so we’re not looking at one pulse of events leading to today’s species, at all. Ancient humans and modern humans were both part of a much longer story.

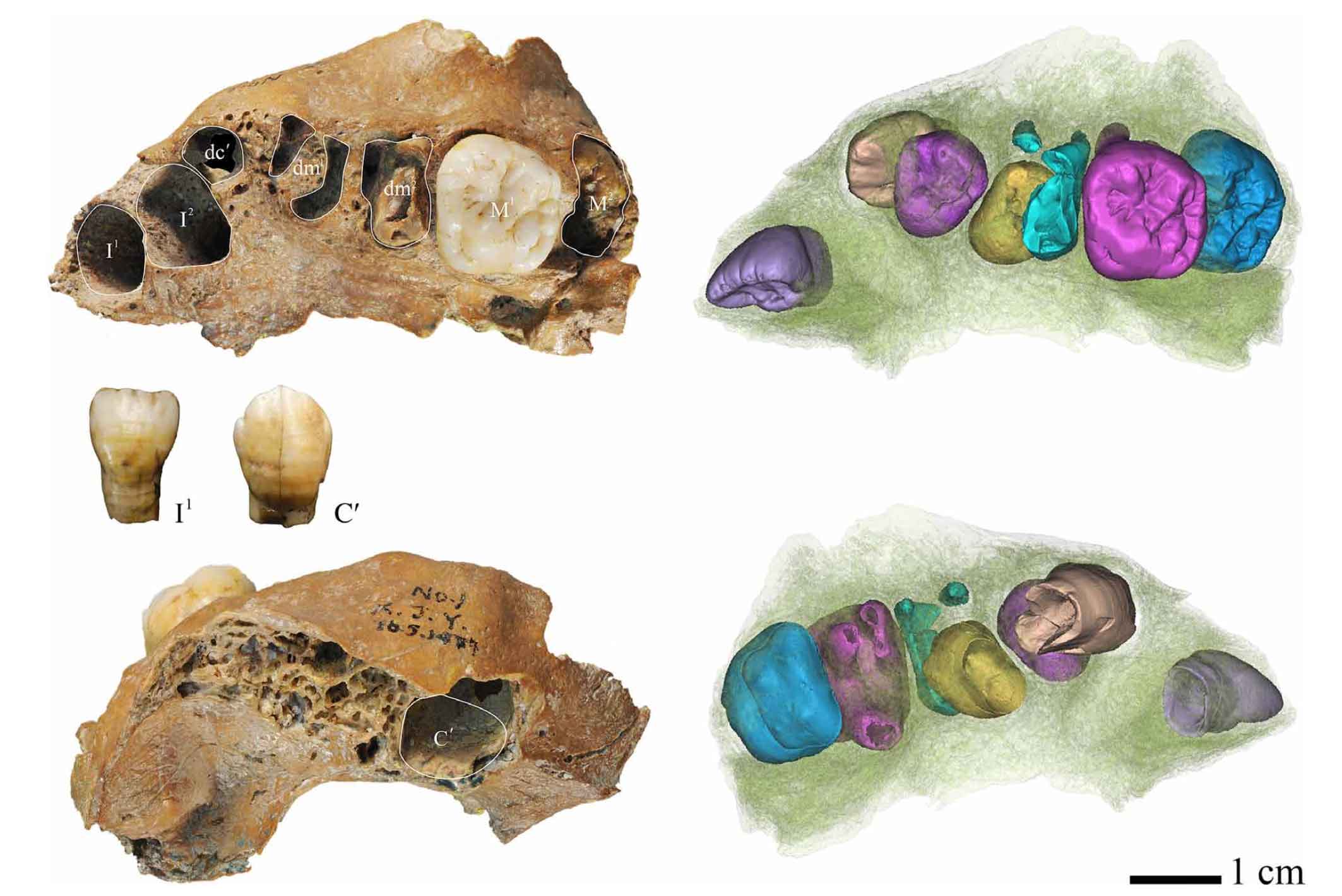

This seems like a parallel case to the island of Flores, where hominins were living and making stone tools by a million years ago. Some of those Flores hominins survived, and we find their remains as Homo floresiensis, with one fragment of jaw 800,000 years old, and more skeletal remains in the period leading up to 65,000 years ago from Liang Bua cave.

Many archaeologists doubt that any hominins 700,000 years ago, or a million years ago, or even Neandertals 100,000 years ago, had the cultural and cognitive ability to make boats. They think it is more likely that some “lucky” individuals were caught up in a tsunami, and washed across the sea from Java or Borneo to these islands.

To support this idea, they point to the 2004 tsunami that affected Aceh, Sumatra, and washed many people far out to sea. Some of them survived for many days before being rescued, as described in this article from the Telegraph.

Nothing about that idea is impossible. Maybe some ancient hominins were lucky survivors. But the notion gives early hominins very little credit for knowledge of their environment.

Some scientists start from the notion that we cannot assume “complex” behavior without extraordinary evidence. But what is “complex”? Is it hard to imagine that a medium-sized mammal species, which relies on foraging across 100 square kilometers or more for high-energy foods, would be aware of islands that are in sight?

Personally, I have a different opinion. I think we have to recognize a continuum of abilities. Extraordinary ideas and abilities probably existed in most ancient populations. Today, in our very large population with huge economic and social incentives for innovation and discovery, those abilities can change the world. But in the past, in low-density populations living on the edge of survival, most innovations could never have become sustained, long-term traditions that leave an abundance of archaeological evidence.

Nonetheless, they changed the world for an individual, or a group.

When it comes to colonizing a new island, it is the exceptional that matters. In fact, if crossings were regular, island populations could never evolve to be very different from nearby mainland populations. It is the very fact that crossing is rare that allows island adaptations to emerge after the population is established.

But it is also the group that matters. A single individual cannot found a new population.

When you look at these places in island Southeast Asia with early hominin activity, ancient sea levels were much lower and all these islands are one or two small hops across narrow straits. Palawan is an island between Borneo and the Philippines, and today these water crossings are hundreds of kilometers, but in the past they may have been as narrow as ten kilometers.

That’s not very far to imagine hominin individuals making crossings, if they were already playing with very basic ways of crossing rivers and using near-beach water resources.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.