Features of the Grecian ape raise questions about early hominins

A review of work published in 2017 describing fossil material of Graecopithecus freybergi from Greece and Bulgaria.

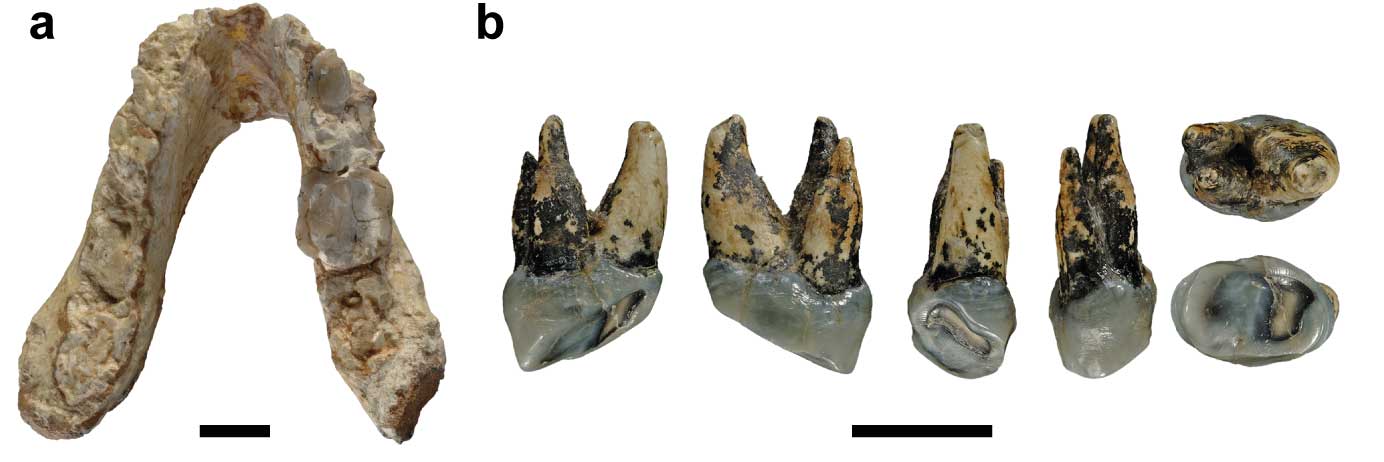

Today, Jochen Fuss and colleagues have published a new description of the morphology of a mandible of Graecopithecus freybergi, from Pyrgos Vassilissis Amalia, Greece: “Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe”. They carried out microCT imaging of the mandible and another fourth premolar attributed to Graecopithecus from Bulgaria.

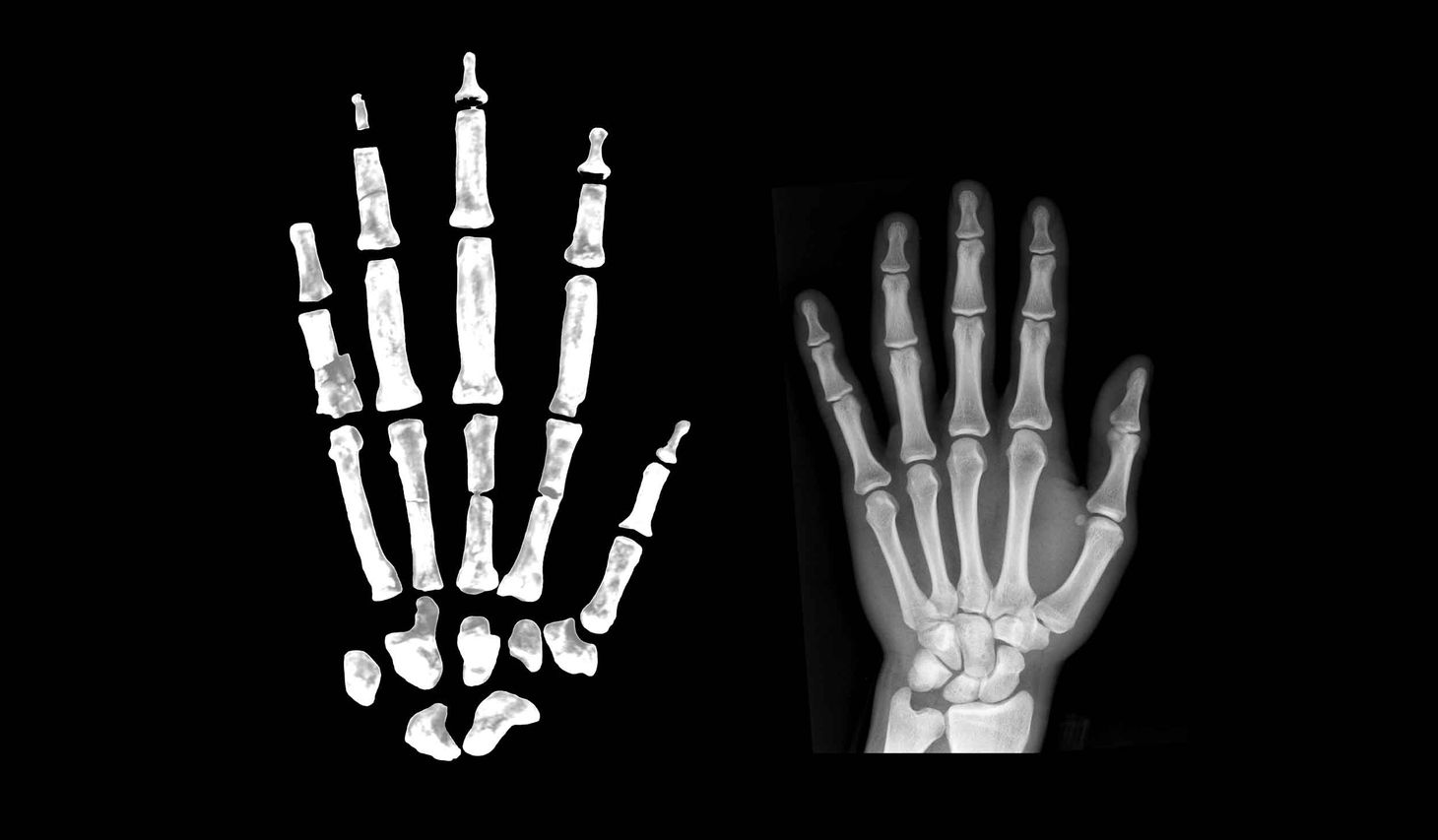

Fuss and colleagues show that the fourth premolar root configuration has some similarities with Ardipithecus, Sahelanthropus and Australopithecus. On this basis, they argue that Graecopithecus should be accepted as a member of the human clade, a hominin, closer to humans than chimpanzees and bonobos.

They go further. These Graecopithecus specimens are both older than 7 million years, making them earlier than any known hominin in Africa. So Fuss and colleagues claim that the origin of the hominin clade may itself have been in Europe.

More fossils are needed but at this point it seems likely that the Eastern Mediterranean needs to be considered as just as likely a place of hominine diversification and hominin origins as tropical Africa.

Is it going too far to say that this fossil jaw is the earliest hominin?

Here’s what I think: Paleoanthropology must move past the point where a mandibular fragment is accepted as sufficient evidence.

As blog readers are my witnesses, if I ever describe an unassociated mandibular fragment, I will never claim it is the earliest hominin, the earliest Homo, or the earliest modern human. Again and again, discoveries of relatively complete skeletal evidence have shown that different hominin (and ape) lineages had mosaic morphological patterns across the skeleton. Parallelism and convergence among lineages have been widespread in our evolutionary tree, and no single feature or fragment can accurately indicate relationships.

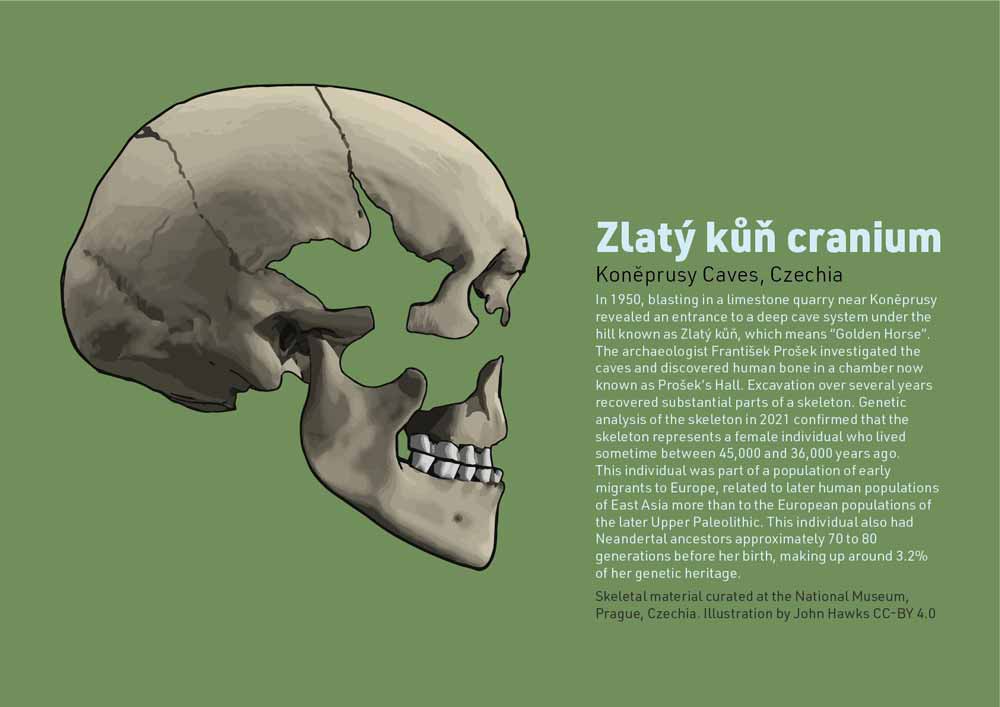

What’s worse, when we look at the earliest hominins, very few scientists have actually examined the evidence. Ann Gibbons wrote in 2006 that only one scientist at that time had seen all the key fossils, and for all anyone knows that may still be the case – since one of the most important specimens remains unpublished fifteen years after its discovery. Most scientists have been mere spectators, forced to look at cartoon images of skull and pelvis reconstructions that have never to my knowledge been examined by any independent scientist.

I don’t want to take away from the value of the study of Graecopithecus here. It’s pretty cool that Fuss and colleagues were able to find some hidden morphological clues in these very fragmentary specimens. That mandible has only one good tooth in it!

With very little to go on, they have done an admirable job of focusing on some interesting dental features that have been seen as important in the early evolution of hominins. I think the study is valuable and I do not question any of the morphological findings.

But consider the example of Ardipithecus. It has a partial skeleton with impressive cranial, dental, and postcranial morphology, and reasonable scientists still cannot decide if it is a hominin. If anyone actually thought we could trust the premolar roots, we wouldn’t be arguing over Ardi.

I think we should take seriously that Graecopithecus premolar root morphology may be yet another demonstration that supposed “hominin” characters actually evolved in other branches of apes during the Miocene. This feature is far from alone. Many other features that supposedly link Ardipithecus or Sahelanthropus with hominins are also found in other Miocene fossils. My colleagues and I documented some of these Miocene ape-like features in Sahelanthropus in 2006.

We need to look with a more critical eye at the fossil evidence for the earliest hominins. They really share very few features with later hominins like Australopithecus. I think we should consider that they might instead be part of a diversity of apes that are continuous across parts of Africa and Europe. Our real ancestry during this earliest phase of our evolution may still be undiscovered.

References

Fuss J, Spassov N, Begun DR, Böhme M (2017) Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177127

Wolpoff, M. H., Hawks, J., Senut, B., Pickford, M., & Ahern, J. (2006). An ape or the ape: is the Toumaï cranium TM 266 a hominid. PaleoAnthropology, 2006, 36-50. https://paleoanthro.org/static/journal/content/PA20060036.pdf

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.