Did giant humans walk the Middle Pleistocene earth?

A National Geographic documentary program prompts questions about some fossils from South Africa with large body size estimates.

This post is from 2005. More recent research has shifted much of what scientists used to think about Middle Pleistocene hominins in Africa. This research is covered in more recent posts on the blog. The post here about body size in southern African fossils of the Middle Pleistocene remains as a historical picture of the state of science in the mid-2000s.

A number of readers have been asking what the deal is with the “Goliath” specimen discussed by Lee Berger (and reconstructed by him and Steve Churchill) in the National Geographic program, “Searching for the Ultimate Survivor.” The femoral fragment found by Berger himself was apparently from Hoedjiespunt, around 300,000 years old. The specimen itself has not yet been reported.

The reconstruction shown on the program is based on the Kabwe cranial and postcranial remains. The Kabwe skull is the best known specimen from the site, but there are also another maxilla and postcrania representing three or more individuals. One (E719) of two innominate bones (os coxae) and one femur (E 907) are quite large, although they probably do not belong to the same individual as the skull (Wolpoff 1999). I would assume that the full-body reconstruction on the program used these to estimate and model a very large body size.

“Ultimate Survivor” discusses the “Goliaths” living in Europe, which means that they are talking about Homo heidelbergensis. There is a clear division of opinion about this species in the field. Some researchers, myself included, think it is a superfluous name that doesn’t describe a real ancient reproductive community, and so we tend not to use it at all. But among those who believe that H. heidelbergensis is valid, there are essentially two viewpoints. Some would limit its application to European fossils only, which is where the type specimen, the Mauer mandible, was found. Others would apply H. heidelbergensis much more broadly to essentially all Middle Pleistocene European and African fossils, and some specimens from China as well. In this usage, H. heidelbergensis is basically inclusive of all specimens that have been called “archaic Homo sapiens, on the basis of enlarged brain size compared to earlier humans combined with the lack of most of the distinctive features of Neandertals.

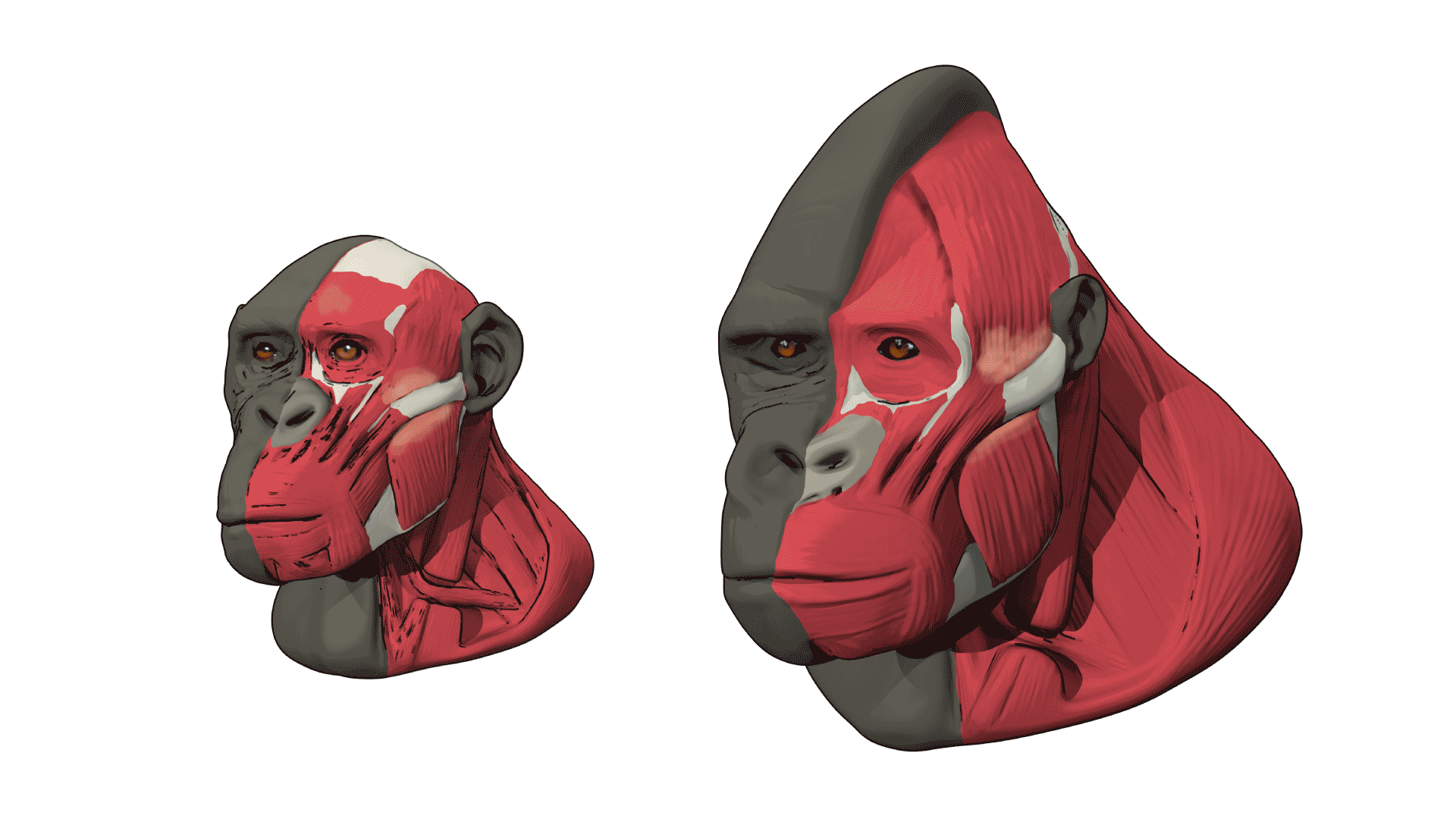

So the question is, were Middle Pleistocene humans a race of giants? There is no question that there were some individuals with large mass. The large Kabwe specimen is one; the individual represented by the very broad Sima de los Huesos pelvis is another – probably the most massive individual in the Middle Pleistocene record. These large specimens had masses upward of 80 to 90 kg, and are more massive than any Early Pleistocene humans, who averaged only between 60 and 70 kg.

But these large specimens provide only a small part of the overall picture of body size. The multiple skeletal remains from the single site of Kabwe alone indicate a range of body sizes. Not only in Africa but elsewhere there is clear evidence of a mixture of smaller and larger specimens. As shown by Ruff et al. (1997), this range of variation is not more extensive than in living human populations. Part of the variation is related to climate (higher latitude populations are more massive), part is probably due to sex (the largest specimens are undoubtedly males, meaning that there must have been a range of smaller female individuals also). But whetever the sources of variation they were substantial and did not greatly change after the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene.

The large body size of some Middle Pleistocene fossil individuals, as well as the Late Pleistocene Neandertals, has led to considerable speculation about their adaptation. Much of this centers around the assertion that early humans were greatly powerful and muscular compared to recent people. This assertion is supported by the increased shaft thickness of the long bones of many early humans. These shafts generally have quite thick cortical bone and reduced medullary cavities; not only compared to recent people but also to early Holocene skeletal remains. Since early farmers certainly worked hard and did not lead lives of luxury, the archaic humans stand out as robust.

Perhaps world-class athletes—at least those before the widespread use of anabolic steroids—offer a closer approximation to the body build and mass of archaic Homo sapiens. Tanner (1964) reported on the mass and proportions of athletes in the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, and the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. The competitors who most closely approximate the build of Neanderthals were the throwers, weight-lifters and wrestlers. Some of these men weighed as much as 91 kg, even though they were narrower across the hips than most Neanderthals. Using a larger, more muscular living human reference sample could produce even larger and perhaps more realistic body-mass estimates (Kappelman 1997:127).

Of course, I weigh as much as 91 kg, and without making any claims about how narrow I am at the hips, my body proportions are not especially Neandertal-like. I doubt that an Olympic weightlifter would make a better model of a Neandertal than I do. The specialized muscle building regimen necessary for performance athletes is not part of the standard mode of human growth and development. Almost certainly a Neandertal with the lean body mass of a performance athlete would be at a huge energetic disadvantage without a substantial fat store, since the availability of food for hunter-gatherers is neither uniform nor uninterrupted. Today’s hunter-gatherers are not particularly muscle-bound – although they are strong and lean, they are not “cut,” and when healthy they have noticeable fat stores. So while I would not suggest that archaic humans were by any means portly, I would suggest that if they had high mass estimates, then a substantial part of that must be modeled as fat rather than pure muscle.

The relatively rapid decrease in modern human body mass during the past 90,000 yr is a dramatic contrast to the large body mass of archaic Homo during the preceding two million years. What selection pressures could have resulted in both smaller body mass and larger relative brain size in modern humans? These changes do not seem to be tightly linked to technological innovation, although the less sturdily constructed skeleton implicates different behaviours, suggesting that modern humans adopted increasingly less active lifestyles. Now, rather than focusing solely on models that favour selection for ever-larger brains, we should examine the possibility that the pattern in modern humans was driven by selection for smaller bodies, perhaps favoured by a social structure that relied on more cooperative foraging and better communication skills (Kappelman 1997:127).

We can add an additional possibility: that increased dietary constraints resulted from population size increases, and that Late Pleistocene humans decreased in body size as a secular trend. It is almost certainly true that a secular trend toward lower mass occurred during the Holocene with the advent of agricultural subsistence. The lower protein and other nutritional content of early agricultural diets combined with the increased incidence of epidemic diseases during childhood both resulted in smaller adult body sizes. Since the industrial revolution, this secular trend has reversed in societies with increasingly Westernized diets.

Moreover evidence from the past 40 years has indicated that the body size differences among human populations have begun to decrease as nutrition has improved in developing nations:

Current analyses indicate that body mass varies inversely with mean annual temperature in males (r=-0.27, P < 0.001) and females (r=-0.28, P < 0.001), as does the BMI (males: r=-0.22, P=0.001; females: r=-0.30, P < 0.001). The surface area/body mass ratio is positively correlated with temperature in both sexes (males: r=0.29, P < 0.001; females: r=0.34, P < 0.001), whereas the relationship between RSH and temperature is negative (males: r=-0.37, P < 0.001; females: r=-0.46, P < 0.001). These results are consistent with previous work showing that humans follow the ecological rules of Bergmann and Allen. However, the slope of the best-fit regressions between measures of body mass (i.e., mass, BMI, and surface area/mass) and temperature are more modest than those presented by Roberts. These differences appear to be attributable to secular trends in mass, particularly among tropical populations. Body mass and the BMI have increased over the last 40 years, whereas the surface area/body mass ratio has decreased. These findings indicate that, although climatic factors continue to be significant correlates of world-wide variation in human body size and morphology, differential changes in nutrition among tropical, developing world populations have moderated their influence (Katzmarzyk and Leonard 1998:483).

This means that mass is approaching the same situation as stature, where any prediction of Allen’s rule appears to be partly cancelled by the tall present-day stature of Northern Europeans, which is in large part a recent, post-industrial development.

So in my view, the body size of Middle Pleistocene humans was influenced by not only their activity pattern and adaptation to locomotion, but also their diet and body composition. They cannot be described as giants, or “Goliaths” compared to recent humans. In particular, the mean body sizes of people living today in industrialized societies are very similar to those of Middle Pleistocene humans.

The body size in Western countries today is a function of genes acting in an environment with nearly maximal nutrition and minimal disease and parasite load. In archaic humans, evidence suggests a diet very high in animal protein, and the small population sizes and low densities would likely maintain a low rate of acute communicable diseases and parasites. Unlike recent hunter-gatherers who occupy lands historically unused by agriculturalists, archaic humans could live and forage in the most productive habitats with the most abundant food sources. In short, archaic humans were probably healthier and better-fed than their later Upper Paleolithic and Holocene counterparts.

The Middle Pleistocene saw the most extensive increases in human brain sizes during all of human evolution. It is interesting to consider the role of diet and population density in creating the circumstances during which this increase happened.

References:

Kappelman J. 1997. They might be giants. Nature 387:126-127.

Katzmarzyk PT and Leonard WR. 1998. Climatic influences on human body size and proportions: ecological adaptations and secular trends. Am J Phys Anthropol 106(4):483-503.

Ruff CB, Trinkaus E, Holliday TW. 1997. Body mass and encephalization in Pleistocene Homo. Nature 387:173-176.

Wolpoff MH. 1999. Paleoanthropology. McGraw-Hill, New York.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.