A case study of race and medicine: the BiDil trial

I review news coverage of a drug marketed to African-American cardiology patients, and think about the impact of ancestry on health.

The New York Times reports on the FDA approval of the drug BiDil (via Gene Expression). The story is also covered by Time magazine and Science.

From the article:

Although the BiDil label will say the drug is for self-identified black patients, many cardiologists believe BiDil will work for many people of other races as well. Wall Street is factoring use of the drug by people of other races into its forecasts for BiDil. Analysts' sales predictions range from $500 million to $1 billion by 2010.

BiDil is actually nothing new; it is a combined dosage of two generic drugs. Studies in the 1980's showed that the combination had no clinical benefit for congestive heart failure, but further work by its maker, NitroMed, showed that some patients did benefit -- especially patients of African descent. Even so, the FDA required that its benefits be shown in a clinical trial of African-Americans before approving its use. The trial showed a clear benefit: in black Americans, the drug leads to a 43 percent reduction in the rate of death from heart failure. The benefit was so pronounced that the study was halted last year in order to provide the medication to all participants.

Medical studies use race as a “placeholder”

Why should the drug work in blacks but not in other groups? The short answer to this question is that we don't know whether it really doesn't work for individuals. The outcome of a trial depends on how researchers identify and divide groups for analysis.

The drug apparently doesn't result in health improvement when applied to large random samples of white Americans. But that doesn't mean that some would not benefit from the treatment. Nor does it mean that people of other backgrounds might not benefit. And conversely, it is not clear that every African-American will be best served by the medication: after all, the population of African-Americans includes people with a wide range of ancestries, some with a relatively high proportion of ancestry from Europe or the Americas.

I like the way this researcher puts the problem in the Time article:

"Race is a placeholder for something else," says Dr. Clyde Yancy, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and a BiDil investigator. "And that's probably a mix of biomarkers, demographics and genes."

The point is, it would be more accurate if the genes underlying the difference were identified, and if potential patients were genotyped for those genes. That would find the best candidates for the treatment, and would leave out those who either would not benefit or who might be harmed by it.

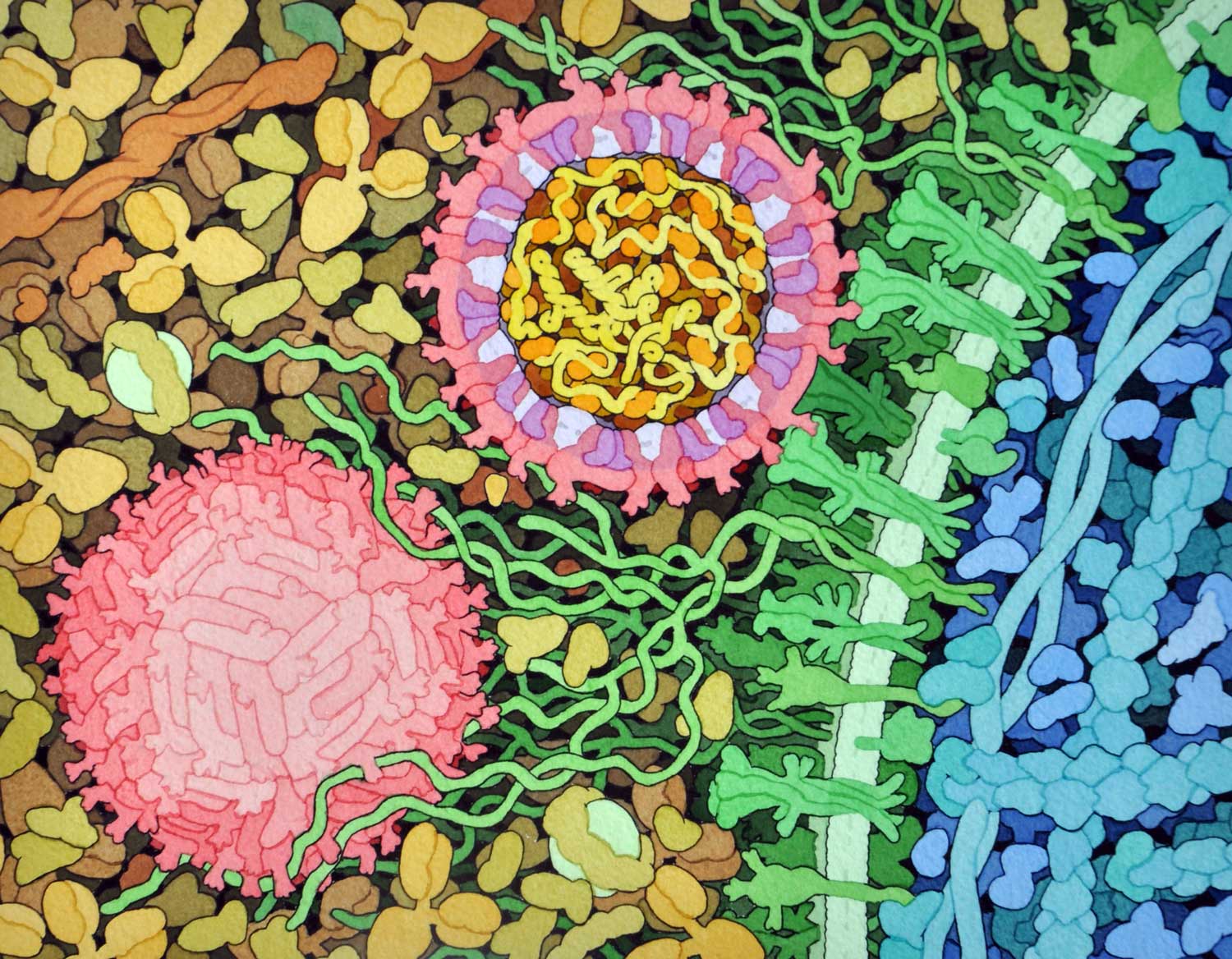

The differences between people in the activity of the drug appear to be related to the metabolism of nitric oxide. Congestive heart failure leads to a deficiency of nitric oxide, which may have a protective effect on heart tissue. The full chain of nitric oxide production enzymes and effects is not yet understood; as excess nitric oxide can also damage the heart by causing an overgrowth of cardiac muscle tissue. But it appears that there are differences on average between African-Americans and white Americans in the effect of heart failure on nitric oxide levels. BiDil stimulates the production of nitric oxide, which evidently benefits blacks to a greater extent than whites.

Pharmacogenomics; or, bringing more drugs to market

In a news report by Robert F. Service, Science magazine is calling the drug a step on the road to pharmacogenomics, the application of treatments based on the unique combinations of alleles carried by each individual. The basic idea is that different people metabolize medicines differently and have different levels of activation of different genes, so that no one treatment affects everyone equally. If the effects of a drug could be predicted against different genetic backgrounds, both doses and combinations of drugs could be customized to fit the alleles that an individual has. From the article:

Although pharmacogenomics only recently entered the lexicon, the notion of treating populations based on the genes involved in health and disease dates from the 1950s. That's when researchers caught an initial glimpse that the speed at which different people metabolized drugs in their system was linked to genetics. But it took another 40 years to progress from those hints to medicines. In 1997, Genentech's Herceptin was approved to fight a form of breast cancer in which cancer cells overexpressed a protein called the HER2 receptor. In 2001, Novartis won approval for Gleevec to treat a form of cancer called chronic myeloid leukemia, in which an aberrant gene triggers a proliferation of white blood cells. And last year, ImClone's Erbitux went on sale to fight colon cancer by targeting a growth factor receptor on tumor cells. Since 1996, doctors have also genotyped the HIV viruses present in AIDS patients to help them select the best combination of drugs to treat the disease. The completion of the human genome project in 2001 allowed drugmakers to scan humanity's entire genetic sequence for links to a wide swath of diseases.

While this increased understanding of variability will likely result in great improvements in care, it will also result in greater potential for manufacturers seeking approval for new drugs and dosages. The Science article reviews the case of warfarin, a potent blood thinning medication whose effects are now known to vary in people with different genetic backgrounds, some of which are correlated with traditional racial groups:

The bottom line for physicians is both obvious and subtle, Martin says: Genotyping patients can save lives, and finding the right dosage may help get a drug through clinical trials. A traditionally run clinical trial will select a dosage that ensures safety for all participants, Peltz points out. If 10% of patients can tolerate only a low dose of a particular drug, that dosage will become the standard of care. That means 90% of patients won't receive an optimal dose, decreasing the chance that the drug will be shown to be effective. "The real value is in increasing the probability of bringing a compound to market," says Nicholas Dracopoli, a pharmacogenomics expert at Bristol-Myers Squibb in Princeton, New Jersey.

All in all, this promises a better outcome for everyone, and in that context it is good to see that the underlying science tends to drive manufacturers to make better decisions about development at the same time it may lead to better treatments.

What about race?

The article in Time, by Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates, focuses in more detail on the race issue, including the objections that many have raised to the research and the suspicions that exist within the African-American community:

The scars left by Tuskegee are slow to heal in the African-American community, and many blacks remain deeply suspicious of anything that approaches the emotionally charged intersection of race and medicine.

The AIDS epidemic is a prime example. According to the Centers for Disease Control, blacks account for 50% of new HIV and AIDS cases in the U.S., although they represent only 13% of the population. African-American women are especially at risk; their annual AIDS case rate is 25 times that of white women. Citing those statistics, significant numbers of black Americans subscribe to various AIDS conspiracy theories. According to a poll conducted for the Rand Corp. last January, 53% of black Americans surveyed believe there is a cure for AIDS that is being withheld from the poor, and 15% believe the disease was created by the government in order to control the black population. Phil Wilson, director of the Black AIDS Institute, says such attitudes are hampering his work with antiretroviral drugs. "The most common thing we hear with AIDS drugs is, 'Oh, they're going to experiment on you,'" he says. "The most cited example is the Tuskegee trials, even though most of us don't even know what Tuskegee was."

Blacks have good reason to be suspicious of studies like this, and not only for a historical reason. Race is a miserable substitute for the knowledge of alleles and genotypes in a study like this one.

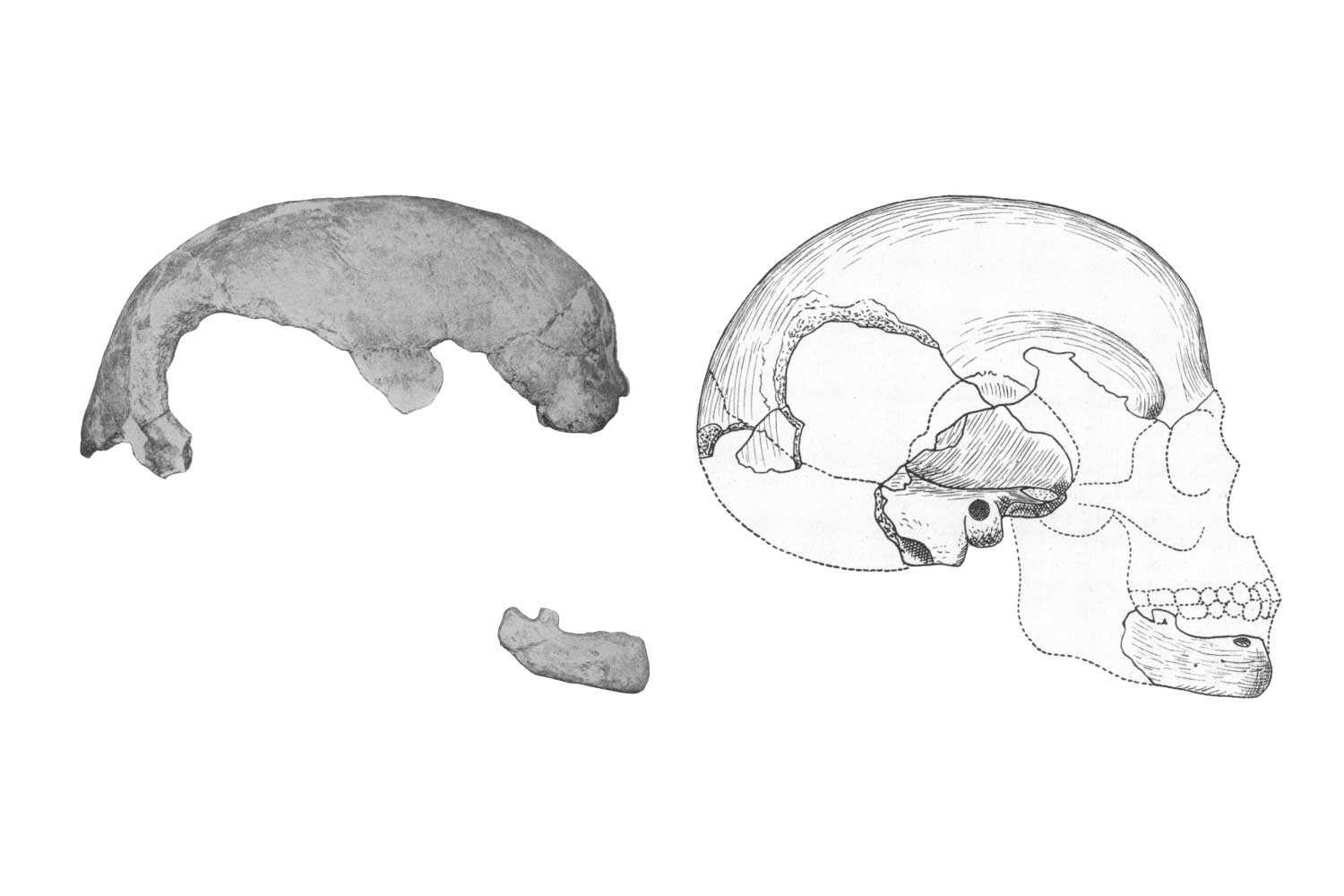

Compared to other populations in the world, Africans are more genetically variable. Lumping study subjects and computing an average is probably a bad way to predict how any drug will affect an entire population. The problem is worse when applied to African-Americans, which share much of the genetic diversity of Africans, but also include a relatively high proportion of alleles that are common in Europeans—a proportion that varies greatly from individual to individual. And the socioeconomic and cultural differences between many black and white Americans also may affect the response to drugs and other medical treatments.

In short, if physicians had better information than race alone, they had better be using it.

The problem is that they don't. Medical studies now recognize race as a valid category to consider, but many equally informative differences among subjects are still ignored. Drugs interact with genes, with foods, with environments, and with habits in ways that are largely unknown. Until these kinds of variables are tested more fully, the promise of pharmacogenomics will remain only a hope.

On the other hand, testing drugs based on information about racial groups may be a step forward when compared to total ignorance about individual ancestries. I'm reminded of an episode of M*A*S*H where Klinger was acting sick and nobody believed him. Not until another soldier started having the same symptoms did Hawkeye and B.J. make the connection: A drug had been administered to the entire camp, and Klinger was having a reaction. The two doctors knew from an obscure medical study that people of Jewish descent sometimes had complications, and they made the connection that Klinger's Lebanese ancestry might make him susceptible as well.

Ancestry is an important part of understanding what has gone wrong when someone is sick, and the more doctors use it, the better. The challenge is to make the information really relevant at a genetic level, and not merely folk tales about race.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.