Why do male bonobos have such low body fat?

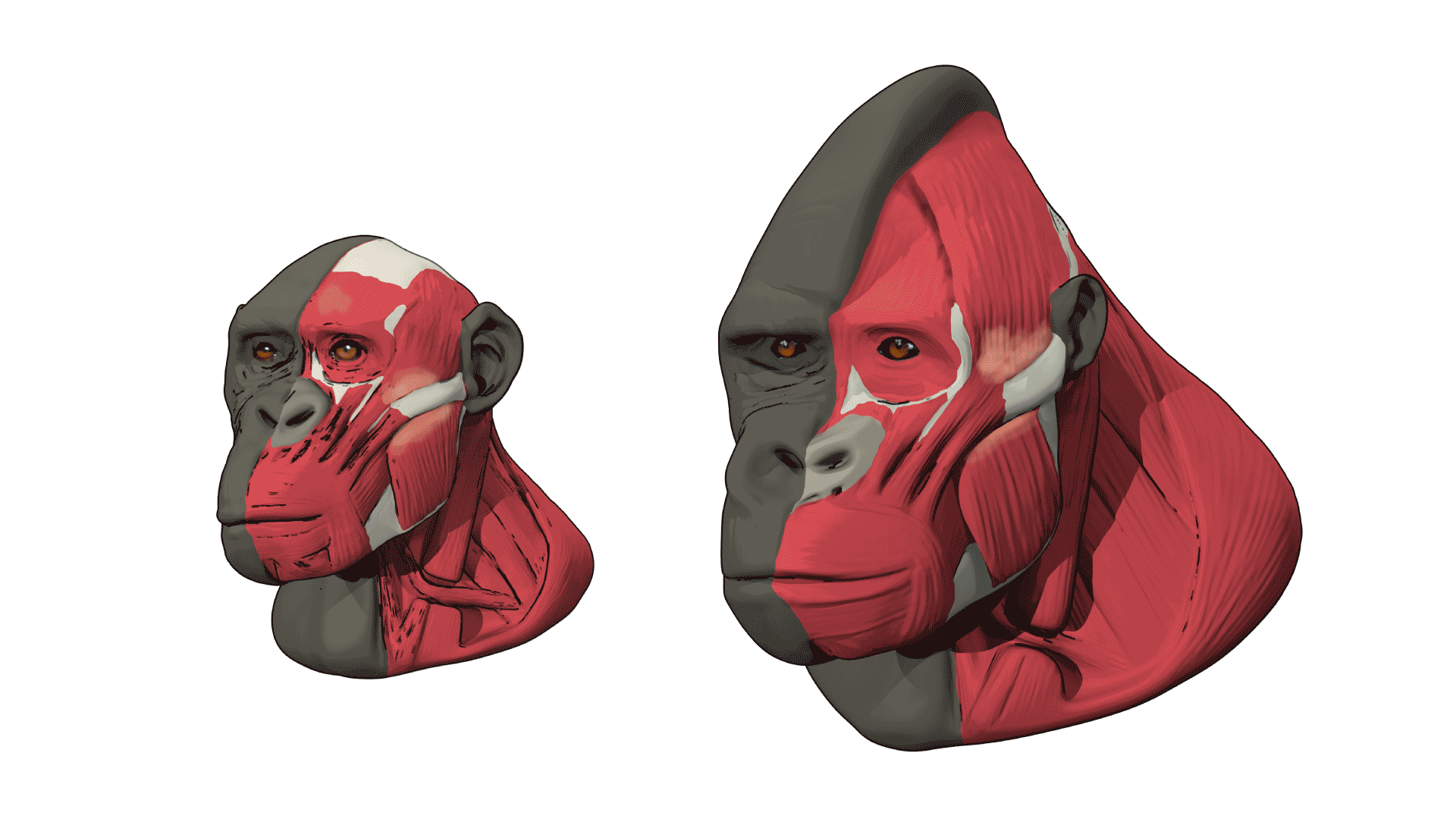

Work by Adrienne Zihlman and Debra Bolter looks at the interesting tissue proportions and what they may imply about energy and diet.

I can’t be the only one surprised at how little body fat male bonobos have. A study of bonobo dissections by Adrienne Zihlman and Debra Bolter (2015) included data from six female and seven male bonobos collected over many years. The females had very low body fat percentages, with the highest value only 8.6% and three of the six females under 1.2%. But the males were the interesting story, with no male among the seven measured as high as 0.01% body fat.

As Zihlman and Bolter explain, these are minimum estimates, since the necropsied bonobos did not necessarily include fat included in the viscera or near internal organs, and fat that could not be dissected as separate chunks was not weighed separately. But subcutaneous fat and other small adipose areas are included in this estimate, and comparable values for male humans are upward of 20%. They comment on the surprising finding:

The negligible measurable fat in all seven P. paniscus males was unexpected, overriding captivity, age, and body mass. Among wild chimpanzees, there is little indication of an ability to mobilize fat stores during times of caloric restriction, a key adaptive feature found in orangutans and possibly to a lesser degree in gorillas (24, 52, 53). Without selection pressure for storage fat, and with over half of body mass in muscle, the male P. paniscus does not easily accumulate body fat, even under optimal circumstances of captivity. Remarkably, none of the males and females manifested detrimental health as a consequence of having little fat, in stark contrast to H. sapiens.

I was interested in whether this is a bonobo-specific phenomenon. Zihlman and McFarland (2000) dissected four captive gorillas and found both males and females to have substantial body fat percentages, ranging from 19.4% to 44%. Wolfgang Dittus (2013) reported on the body fat distribution of wild toque macaques, finding that they had approximately 2.1% body fat, more than 80% carried within the viscera and other intra-abdominal areas and only a small amount subcutaneously. Males and females did not differ on average.

Interestingly, a study of zoo chimpanzees by Elaine Videan and colleagues (2007) found that no male chimpanzees could be categorized as overweight, and that they differed from females in skinfold and triglyceride levels. From that paper:

The range of serum triglyceride and glucose levels for male chimpanzees was considerably smaller than that of female chimpanzees (Figs. 2, 3). In fact, none of the male chimpanzees in this study had serum triglyceride levels above 150mg/dl (< 150 mg/dl 5 normal human reference range) despite having BMIs that ranged as high as 149.5. In addition, most of the mean skinfold measurements for male chimpanzees were half that of the female values (Table 1). We hypothesize that the high BMIs observed in many of the male chimpanzees in this study reflects high lean body mass (i.e., muscle mass) rather than high body fat.

So there does seem to be something about male chimpanzees and bonobos.

Lest you think that human body fat is just a post-agricultural phenomenon, Herman Pontzer and colleagues (2012) reported on body composition in the Hadza population of Tanzania, who live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In that population, women range from 12.4 to 27.7 percent body fat, and men range from 7.4 to 23.1 percent body fat. This is much less than in Westernized societies and is also less than in subsistence farmers, although the difference there is not so great as most might assume. There is a story of body fat in human evolution, and certainly the high body fat composition of humans—even human foragers—contrasts with most wild primate populations. It may be that bonobos and chimpanzees are not the appropriate comparison because of their own distinctive evolutionary trajectories.

References

Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Wood BM, Mabulla AZP, Racette SB, Marlowe FW (2012) Hunter-Gatherer Energetics and Human Obesity. PLoS ONE 7(7): e40503. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040503

Dittus WP (2013). Arboreal adaptations of body fat in wild toque macaques (Macaca sinica) and the evolution of adiposity in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 152(3), 333-344. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22351

Videan, E. N., Fritz, J., & Murphy, J. (2007). Development of guidelines for assessing obesity in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Zoo biology, 26(2), 93-104.

Zihlman AL, Bolter DR (2015). Body composition in Pan paniscus compared with Homo sapiens has implications for changes during human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201505071. doi:10.1073/pnas.1505071112

Zihlman, A. L., & McFarland, R. K. (2000). Body mass in lowland gorillas: a quantitative analysis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 113(1), 61-78.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.