Did somebody bury the bones of Toumaï?

I recount the complicated story of how a discoverer of the Toumaï skull has raised doubts about its context.

Note: This post was published in 2009. It describes several published articles in a variety of scholarly journals. The questions raised here about the original situation of the fossils at the time of discovery are important ones. Those questions do not challenge the status of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis remains as genuine fossils, nor do they affect the anatomical interpretation of the fossils which is based upon their anatomy and not their geological setting. In 2022, postcranial evidence of S. tchadensis was first described, including the femur referenced in this post.

Now if you really want to beat the science press, it helps to have readers who take really obscure journals.

I haven’t written much here about Sahelanthropus. In 2002, I joined a number of other people who doubted the evidence for bipedalism in what was then (and has since been) touted as the “earliest known hominin.” Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. But we weren’t convinced by the evidence. The Toumaï specimen shares some dental similarities with early hominids, but also with a number of Miocene ape genera. Meanwhile the evidence for vertical posture, based on the position of the foramen magnum, seemed weak. We made our case in a 2006 paper in PaleoAnthropology, which is open access.

Since no new evidence has come to light (or at least, to print), that’s where matters stand as far as I’m concerned. I still think the evidence for bipedality in Sahelanthropus is equivocal, and that the specimen’s date may be too old to be a member of the hominin lineage.

Meanwhile, also in 2004 began a strange series of events involving Alain Beauvilain, a geographer working with the original Sahelanthropus excavation project. I have no personal knowledge of the details, aside from the published record – so that’s what I’ll stick to.

Yes, this story does end with camelherders burying fossils….

Dental associations of Toumaï questioned.

First, Beauvilain teamed up with a dentist named Yves Le Guellec, publishing a short paper in the South African Journal of Science that questioned the assignment of a tooth to the Toumaï mandible. Their suggestion was that the tooth must represent a second individual, and that the original research team had mistakenly glued it into the mandible. They did not question other aspects of the original research, and concluded their paper:

The present analysis, based on some Sahalanthropus paratypes, is only one element of the discussion about this genus. It does not modify the basis of the debate concerning the systematic position and palaeoecology of Sahelanthropus (Beauvilain and Le Guellec 2004:144).

That seemed pretty milquetoast to me, and if I’d been blogging at the time (which I wasn’t), I might not even have taken notice.

What was newsworthy about Beauvilain’s comment was the reply by Brunet’s Sahelanthropusresearch team. They provided images, including CT scans, that supported their original assignment of the tooth to the mandible. And then, the reply was followed by a statement signed by 28 other paleoanthropologists, led by F. Clark Howell. Here is that statement in its entirety:

Sir, We, the undersigned, have carefully examined the photographs and digital crown images of a fossilized third molar from the upper Miocene of Chad. This tooth was originally identified by the discoverers (Brunet et al. 2002, Nature 418, 145151) as a right third mandibular molar. A recent paper by Beauvilain and Le Guellec (2004, S. Afr. J. Sci. 100, 142144) claimed that this tooth had been misidentified and was in fact a left lower third molar. Based on crown anatomy evident in the images examined by us, we confirm the identity of this tooth as a right molar, as originally published by Brunet et al. (2002).

Rex Dalton covered the reply in Nature, in a piece titled, “Brickbats for fossil hunter who claims skull has false tooth”. All I can add is, I hope this crew never comes after me.

This exchange continued for a couple more letters, as Beauvilain and Le Guellec found errors in the analyses published by Brunet and colleagues. They may not have been correct about the tooth, but they had showed a string of apparent mistakes made during the research on Toumaï.

Stratigraphy of Sahelanthropus questioned.

That was all in 2004. In 2008, Beauvilain published an article in the South African Journal of Science in which he asserted that neither Toumaï (the type specimen of Sahelanthropus tchadensis) nor the type specimen of Australopithecus bahrelghazali had been found in situ by Brunet’s team. This short article was apparently a reply to a PNAS report on the dating of the two discoveries by Anne-Elizabeth Lebatard and colleagues (2008). That paper placed the two fossils within stratigraphic sequences and provided dates for the strata. Beauvilain (2008) wrote that the placement could not be certain:

From January 1994 to July 2002, the author of the present note was in charge of every palaeontological field expedition that took place in the Chadian desert. In the interests of scientific accuracy, he is compelled to state formally that neither of these fossils was found in situ. The most appropriate word to employ for the two fossils would be that they were 'collected' from their respective localities, which are the sites TM 266 in Toros Menalla and KT 12 in Koro Toro for S. tchadensis and A. bahrelghazali, respectively.

...

The photograph taken by the author at the moment of discovery has been widely published but never with a proper explanation. He thought that the image was sufficiently evocative to indicate the lack of stratigraphical context of the fossil. It is time to correct this omission. In the image, the hollow in the sand to the right of the skull is the exact spot at which Toumaï was found. Almost all the fossils from TM 266 were in similar situations with respect to the substrate. By a curious choice, the photographs of Toumaï published by [Brunet's team] as representing its field context are in reality those of a darkened resin cast, posed in the desert on a ridge of sand created by the northeast winds in February 2004.

Beauvilain did not in this article suggest that the true ages of the fossils might be radically different than those of the strata reported by Lebatard et al. (2008) – a substantial depth of deposit around the Sahelanthropus site falls within a time range between 6.8 and 7.12 million years ago. He does suggest that the aeolian pattern of erosion in the area and some faulting may have caused undercutting of some fossils and substantial movement against the vertical section.

Cosmos magazine picked up this story last year, although I have not seen it reported elsewhere. I noted it here at the time. I haven’t seen any reply to Beauvilain by the rest of the excavation team.

That’s the published record. What did Beauvilain accomplish with this paper? He reiterated his position on the field project and gave clear reasons why he had stepped forward to publish his note on the specimens’ provenience. This additionally presented the context in which he took his own photos of the Toumaï discovery. The photos are the crucial element.

Buried facing Mecca?

Now the story gets weird. Beauvilain’s new paper with Jean-Pierre Watté has been blowing into paleoanthropologists’ inboxes around the world. My library doesn’t get the Bulletin de la Société Géologique de Normandie et des Amis du Muséum du Havre, but I’ve gotten copies of it from three different sources. Considering how widespread my sources are, I know that a good fraction of my colleagues have at least had their chance to read it.

I don’t tend to pass around mere rumors, even if they’re really juicy (you know who you are….). But this is no rumor – it’s a real publication. Nobody quite seems to know what to think about it. So let’s get it out in the open.

Here’s the English version of the abstract:

Was Toumaï (Sahelanthropus tchadensis) buried?

I’m going to give a fairly long summary of their argument, providing English translations of the key points. They have no direct evidence that the bones were altered in position or deliberately arranged, but they do present an interesting circumstantial argument. There are essentially four points:

- The skull was associated with an unusual concentration of fossils. As Beauvilain and Watté (p. 20, my translation) introduce their paper:

While fossils of this site are distant from each other, scattered at random and without concentration of large size, Toumaï was part of a pile of bones. In general, with the exception of skeletal remains belonging to a single individual, concentrations of fossils are rare in Djourab sites. That is why the Chadian coauthors to the discovery said this cluster was a "dustbin of palaeontologists." This expression does not correspond to reality. The "garbage" of paleontologists, and geologists, experienced in this area of Toros-Menalla, as well as that of KB, are of a different nature: broken bones, brittle, "digested" by the desert crust, not identifiable, with sometimes broken glass of beer or demijohns. A skull could not have been left there, unless it was completely hidden beneath the crust. An examination of Figures 1a and 1b can offer a different explanation.

The picture below shows the association. It is not possible to say how unusual this may be without some statistical study of the area around the site. I’m noncommittal, but am willing to accept Beauvilain and Watté’s description at face value.

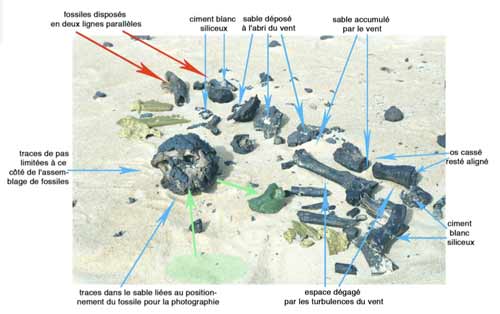

- The arrangement of the bones. I can’t discuss the paper without showing the photographic evidence that Beauvilain and Watté rely upon. So here’s Figure 1b from the paper:

According to the paper, this is the layout of the Toumaï skull and surrounding fossil bones at the time of discovery. Beauvilain and Watté suggest that this is an artificial assemblage of fossil bones. As you can see, they have labeled “two parallel lines” along which the bones are arranged. They do not judge this to be a likely result of aeolian erosion in situ, and consider it a possible sign of a deliberate arrangement of the fossils.

As I’ve noted, Beauvilain (2008) established the reason why he has photos of the original find. With photographic evidence such as this, the constant worry is that some kind of alteration has been made with Photoshop. Has false color been added? Have objects been composited together? I’m no forensic photo expert, but I see no obvious signs of trickery.

Are they really two parallel lines? Clearly there is at least one straight line here (the top one in the figure), with other fossils arranged in rough accordance with that line. It’s not random, but whether collection in an aeolian depression might explain the linear arrangement, I don’t know.

- When it was found, the skull was lying on its left side, with its right side exposed. But both sides of the skull and its adhering matrix appear to have been equally eroded and patinated, including a process of “bluing” the dark matrix, a chemical alteration that occurs on surfaces exposed to air and light. This suggests that the entire skull was exposed for some time. This is not explicable if it was eroding out of a rock layer in situ, but only if it had been rotated, either by aeolian forces undercutting it for some time or because the skull was transported from some other location (p. 23-24).

Also, in favor of the skull having been moved, Beauvilain and Watté suggest that the matrix adhering to the skull appears to be somewhat different from the other fossils:

Par ailleurs, aucune trace n'est visible sur le crâne ou sa gangue de ce ciment blanc, très siliceux et très adhérent aux fossiles, qui caractérise les autres pièces collectées à TM 266, comme celle de la mandibule de Sahelanthropus TM 266-02-154-1, et sur un grand nombre d'ossements de la zone dite de Toros-Menalla. Ces différentes pièces n'ont donc pas strictement le même age (23).

In addition, no trace is visible on the skull or its matrix of this white cement, very silicious and adhering to fossils, which characterizes the other pieces collected at TM 266, including the mandible of Sahelanthropus TM 266-02-154-1, and on a very large number of bones from the zone called Toros-Menalla. These different pieces are therefore not strictly the same age (my translation).

I think these points are fairly compelling. That skull ought to be asymmetrically weathered and patinated unless it has been rotating around a lot. It ought to be more weathered than the surrounding bones, which clearly present a lower profile to the elements.

- The line formed by the fossil bones is oriented toward Mecca. I’ll say right off, this is the least convincing element of their argument. The “parallel lines” in the figure are northeast-southwest, which is only “toward Mecca” in the general sense (as described below). Given a line, it has to point in some direction, and there’s a good chance that it will be within 45 degrees of any random line.

However, it does help to tie the story together. Here is the full scenario, as outlined in the paper’s conclusion (my translation of pp. 24-25):

The location of the skull in relation to the two rows of long bones evokes the disposal of a body reduced to the status of a skeleton.... This arrangement cannot be natural. In view of its configuration, it is suggested that it arose from the desire to give these remains the honor of a burial. The skeleton was reconstructed from the skull conceived as "human". Indeed, this head, which looks like the head of a man, cannot remain indifferent. In this perspective, the authors of the burial -- if that is indeed the case -- would have done their best, according to their anatomical knowledge and the fossils of animals they could find here and there, and that they may have confused with human bones, in order to bring the skull together with the other elements of his body. They put a close to the humeral head and distal end, well-oriented, a femur at the other end of the "corpse". Toumai therefore is subject to a burial in recent times.

Why a burial? The abundance of fossils in this part of the desert makes it so that today, people remark on it but do not think more than that some stones resemble animal bones, including jaws, without giving them much importance. Children play with them. But to the contrary, this skull that so resembles a human skull could not be taken for a toy and abandoned to children.

Who could have been the authors of this burial? The orientation given to the "body" correponds to the diagonal northeast-southwest. This direction is important: it is the line toward Mecca. This burial, if such is the case, could have been done by nomads who cross the region regularly. Muslims since the 11th century with the conversion to Islam of the sovereigns of the first kingdom of Kanem -- the capital of which lay not far from the place where Toumaï was found -- these populations became religious enough to offer a decent burial to their human brothers. In fact, the Muslim religion makes it an obligation to inter cadavers. The precise tradition in which the body must be lain out with the head oriented in the direction of Mecca. Without instruments, believers take the direction of the rising sun, which, near the Tropic of Cancer, is highly variable during the year when it may be in either the northeast or the southeast.

Is it a convincing scenario? It seems a little far-fetched if you imagine that the desert was an untouched wilderness where humans would never have laid eyes on these objects. But to give them as much credit as possible, Beauvilain and Watté note that today’s “desert” was before 1900 much more frequently trafficked than today. Human activities are still widespread in the area and were formerly more so. This is not untrammeled wilderness, and according to the paper it might be very likely for a humanlike skull, laying on the desert floor for decades, to have been encountered by local people and reburied.

At this point, it is an ethnographic question: Other burials must periodically emerge from the ground. What happens to them? Is there other archaeological evidence of reburial of skeletal remains, either in this immediate area or elsewhere in North Africa? I haven’t found any other citations of such a practice, but it must be rare and episodic in any event.

What does this mean?

At the end I have to say I’m ambivalent. I have no real reason to accept or deny this new report or the original studies. Beauvilain has a record of pointing out genuine inaccuracies in the publications of Brunet’s group. Beauvilain and Watté base their specific claim of a recent reburial is only on circumstantial evidence, which is tenuous.

Yet the evidence does seem sufficient to support Beauvilain’s 2008 position as regards the surface collection of the specimens and the possible transport of the skull. Beauvilain (2008) claimed that Toumaï had not been discovered in situ, and that is relation to the published stratigraphy was therefore unclear. At one level, this current paper says nothing more.

Sahelanthropus may still be precisely what its discoverers have claimed: A Late Miocene representative of the human lineage. The fossil is what it is, and the nearby sediments are Late Miocene in age. If people had transported it some short distance and reburied it, it would still probably be Late Miocene in age – although I would want to see somebody do a systematic comparison with local sites to be sure.

At worst, the skull represents a somewhat different date, and is not clearly associated with the accompanying fauna. In that case, a fuller understanding of the local paleontology, along with (hopefully) new discoveries of Sahelanthropus, should clarify matters.

Beauvilain himself appears to be a big booster for Sahelanthropus (having published a trade book on the discovery) and has maintained in each of his critical publications that it is likely the first member of the human lineage. He seems to be aiming at precision in the descriptions, not trashing the species and not offering any new interpretation of its anatomy.

But I’m not a big booster of Sahelanthropus. And there’s one significant thing in this paper that even the sharp-eyed might miss. Something that you might reasonably wonder about, considering the discoverers and describers of Sahelanthropus have never once mentioned it in print.

Toumaï’s skull was found alongside a femur.

References:

Beauvilain A. 2008. The contexts of discovery of Australopithecus bahrelghazali (Abel) and of Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Toumaï): unearthed, embedded in sandstone, or surface collected? S Afr J Sci 104:165-168.

Beauvilain A, Le Guellec Y. 2004. Further details concerning fossils attributed to Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Toumaï). S Afr J Sci 100:142-144.

Beauvilain A, Le Guellec Y. 2004. Reply to Brunet et al. S Afr J Sci 100:445-446.

Beauvilain A, Watté J-P. 2009. Toumaï (Sahelanthropus tchadensis) a-t-il été inhumé? Bulletin de la Société Géologique de Normandie et des Amis du Muséum du Havre 96:19-26.

Brunet M, Guy F, Pilbeam D, Lieberman DE, Likius A, Mackaye HT, Ponce De Len MS,C.P.E.Zollikofer CPE, Vignaud P. 2005. New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad. Nature 434:752?755. doi:10.1038/nature03392

Brunet M and 28 others. 2004. Sahelanthropus tchadensis: the facts. S Afr J Sci 100:443-445.

Dalton R. 2004. Brickbats for fossil hunter who claims skull has false tooth. Nature 430:956. doi:10.1038/430956a

Howell FC and 27 others. 2004. Untitled. S Afr J Sci 100:446.

Lebatard A-E and 13 others. 2008. Cosmogenic nuclide dating of Sahelanthropus tchadensisand Australopithecus bahrelghazali: Mio-Pliocene hominids from Chad. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 105:3226-3231. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708015105

Wolpoff MH, Hawks J, Senut B, Pickford M, Ahern J. 2006. An ape or the ape: Is the Toumaï cranium TM 266 a hominid? PaleoAnthropology 2006: 36-50. PDF

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.