Research highlight: The frontal sinuses of fossil hominins

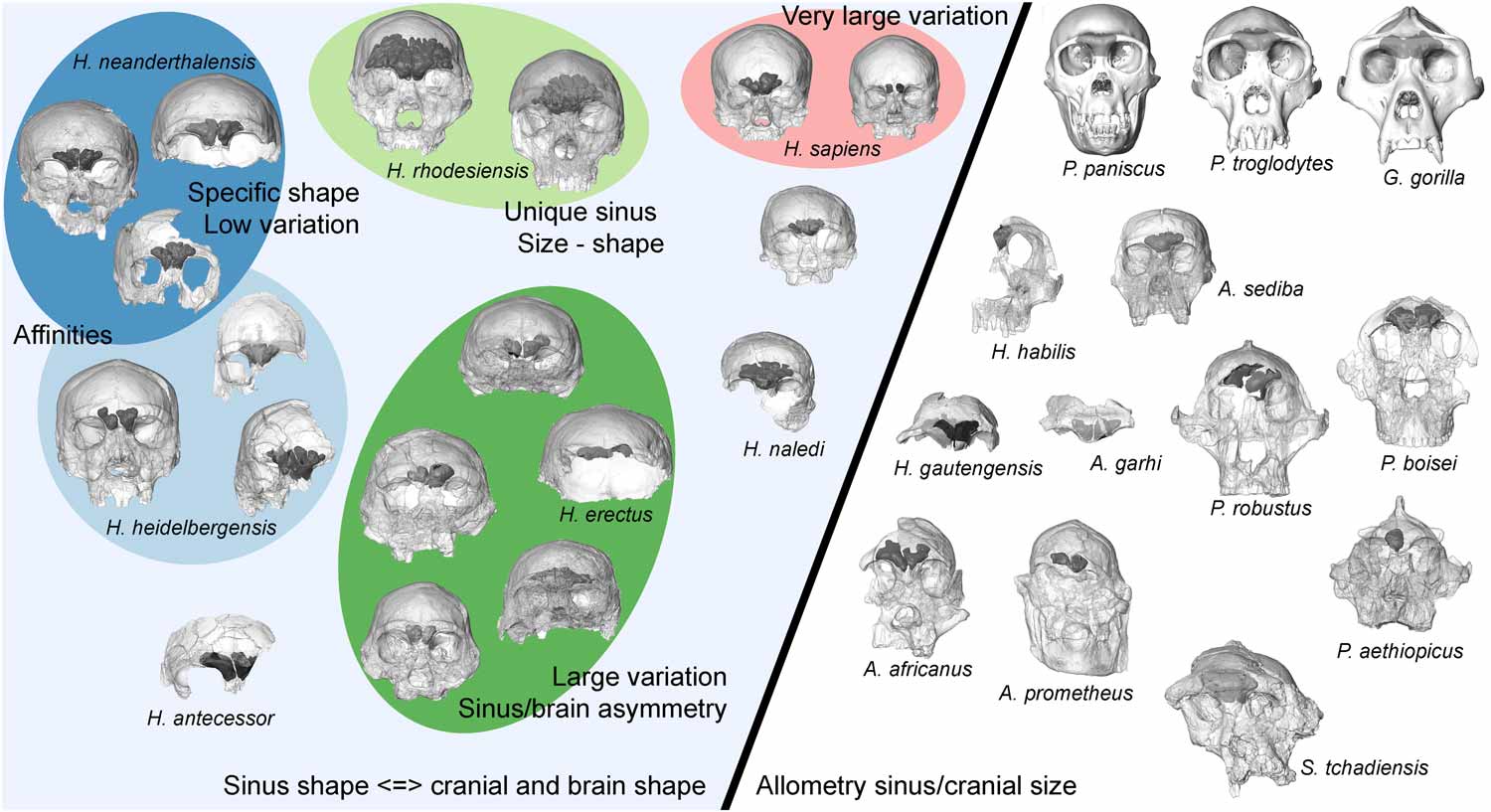

A look inside the skulls of hominins reveals the extensive variation in the form of the internal structures known as the frontal sinuses.

Citation: Balzeau, A., Albessard-Ball, L., Kubicka, A. M., Filippo, A., Beaudet, A., Santos, E., Bienvenu, T., Arsuaga, J.-L., Bartsiokas, A., Berger, L., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Brunet, M., Carlson, K. J., Daura, J., Gorgoulis, V. G., Grine, F. E., Harvati, K., Hawks, J., Herries, A., … Buck, L. T. (2022). Frontal sinuses and human evolution. Science Advances, 8(42), eabp9767. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abp9767

Most people who follow human origins research probably recognize the external anatomy of hominin skulls. But what about their internal anatomy? One famous source of evidence about ancient hominins is the endocranial surface, which sometimes persists as natural endocasts in fossil sites. There are other internal cranial structures, much smaller, that also carry information about hominin adaptation and relationships.

Over the last few years, Antoine Balzeau has been putting together the largest-ever comparison of one of these internal structures, the frontal sinuses. I played a small part in this work due to my familiarity with the cranial morphology of Homo naledi, and I was especially interested in how this species would compare to other hominins.

The paranasal sinuses are remarkably varied within humans and among species of extinct hominins. These are voids within and between the bones of the face and forehead, lined with membranes and filled with air. The sinuses have a complicated developmental history, and they form sometimes bizarre shapes. Paranasal just means “around the nose”, and most people have several connected spaces in this part of their faces. The maxillary sinuses flank the nasal aperture on the left and right sides, and the frontal sinuses extend above the nose, forming a space within the frontal bone.

Some fossils have natural breaks that enable researchers to study the shape and form of the sinuses. But otherwise these are generally hidden from view. The advent of CT scanning during the last 25 years has begun to reveal the form of sinuses inside fossil skulls, enabling scientists to measure and compare them.

One of the great challenges in paleoanthropology is simply putting the same data from different fossils together to create a comparison. This was Antoine's big accomplishment. The paper provides for the first time a massive dataset with images, measurement, and interpretation of the frontal sinus morphology in dozens of fossil hominin skulls.

There is a lot of complexity in these comparisons. Balzeau found it possible to highlight a few conclusions.

- Most early hominins including Australopithecus and Paranthropus have frontal sinus volumes that are predicted by their endocranial volumes. This pattern is the same as found within living species of chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. The larger the skull, the larger the frontal sinus.

- Within Homo the relationship of frontal sinus volume and brain volume does not hold. There is very extensive variation in both volumes and no close relationship.

- Some species or groups within fossil Homo had very distinctive patterns of frontal sinus morphology. Neandertals tend to share a similar size and shape. Fossils like Petralona, Bodo, and Kabwe have very extensive, large frontal sinuses, which are very different from Neandertals—including early members of the Neandertal lineage like Sima de los Huesos.

Some previous researchers have considered that frontal sinuses might reflect adaptations to climate in some way, with cold climate corresponding to large sinus volume. The data from fossil hominins don't support that idea. The largest frontal sinus volumes are found in individuals across a wide array of climates; the Neandertals had medium-sized frontal sinuses. More data from the eastern end of Eurasia would be welcome to add to this comparison; while the equatorial Ngandong, Sangiran, and other samples are included in the study, more northerly samples from China like Dali, Jinniushan, and Harbin are not.

For me, the Homo naledi results are very interesting. The species falls in a range similar to the Dmanisi sample of Homo erectus in both frontal sinus volume and endocranial volume. The LES1 skull and Dmanisi together seem to lie just off the linear relationship of endocranial volume and frontal sinus volume found among great apes, Australopithecus and Paranthropus. LES1 and Dmanisi 4 in particular are very close to StW 505 from Sterkfontein, usually attributed to Australopithecus africanus. The sinus-endocranial relationship in these different forms appears to be conserved from the early phases of our genus up to the later Middle Pleistocene in H. naledi.

That conservation is very interesting in light of the great diversity that appears in some other branches of Homo. Only one H. naledi fossil preserves the shape of the frontal sinus, LES1. The lateral portion of the sinus can be seen in the DH3 fossil skull, but the central part of the browridge has been lost in that fossil. So it's not presently possible to examine the variation of frontal sinus form in H. naledi to see whether the species had a pattern of within-population variation that was limited, like Neandertals, or more extensive as in living people.

There's a lot more to learn about the variation of sinuses among fossil hominins. I expect that most of their evolution has been neutral, without particular adaptive significance. That makes it interesting that fossil Homo has a different pattern than in other forms of hominins and great apes. It's a good question whether other apes have constaints on sinus development that have been relaxed within the larger-brained species of Homo, possibly resulting from architectural changes related to brain size evolution.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.