A critical look at the idea of Australopithecus prometheus

A historical perspective on a species name that was associated with fossils from Makapansgat, South Africa.

Lee Berger and I have a new article out in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology that looks at what may be the biggest issue in hominin taxonomy for the upcoming year: “Australopithecus prometheus is a nomen nudum.”

Our paper concludes that this species was not properly defined back in 1948, and should not be used today for new fossils without a new formal definition.

It’s a short article and the topic is probably obscure for most people interested in reading it. We had to read very carefully through 70-year-old research papers to understand exactly how they relate to the evidence. Along the way, we developed a thorough understanding of the international convention on naming species, and its updates through the years.

So I’ve put together a short Q-and-A about our paper and the topic of Au. prometheus. I hope it helps to deepen people’s interest in a fascinating history.

Why does anybody care about Australopithecus prometheus today?

The short answer is that the name Au. prometheus has come to be associated with the Little Foot skeleton from Sterkfontein.

That skeleton has been in the news, and so prometheus is in the news. For example, last month the Daily Mail announced: “New ‘human ancestor’ discovered”. New Scientist added: “Exclusive: Controversial skeleton may be a new species of early human”.

You can imagine that a lot of folks who follow new developments in human evolution are probably scratching their heads. Prometheus?

“Little Foot” is a skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa, and its formal number is StW 573. Last year I wrote about this skeleton and the scientific opportunities it may provide for human origins research: “Will the ‘most complete skeleton ever’ transform human origins?”

Ron Clarke is the scientist who directed the excavation and study of the skeleton. Back in the 1980s, Clarke began to develop an idea that the hominin fossils from Member 4 of Sterkfontein might have belonged to two different species. One of these was Australopithecus africanus, which is familiar to most students of human origins. The other included Sterkfontein specimens with larger molar and premolar teeth, and with skulls and jaws that suggested larger jaw musculature.

Most scientists attributed such differences to sex, assuming that adult males are larger and more robust-looking that females. Clarke asserted that the differences in teeth and jaw musculature were correlated with facial and cranial features in a way that would not be expected between males and females of the same species. In his opinion, the larger-toothed Sterkfontein fossils were more closely connected to the robust australopithecines, such as those from nearby Swartkrans and Kromdraai.

Clarke assessed that the hypothetical robust-like species was different from Au. africanus. For this species, which in his opinion includes the StW 573 skeleton, he has used the name Au. prometheus.

Clarke’s new preprint with Kathy Kuman discusses the current status of these ideas, and it is available open access: “The skull of StW 573, a 3.67 Ma Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa”. I recommend reading through it.

Is prometheus a new species?

Au. prometheus is far from new. In fact the name is a blast from the past.

Raymond Dart coined the name in 1948 to describe a fragment of hominin occipital bone from Makapansgat, South Africa. A few years later, Dart himself came to believe it was a mistake. Neither this bone nor any of the rest of the Makapansgat fossils described later were a different species from the Taung specimen, which he had named Australopithecus africanus back in 1925. Au. prometheus was soon forgotten.

For most old names in human evolution, that would have been the end of the story. Clarke’s interest in the name, and his attribution of the Little Foot skeleton to Au. prometheus has driven a few other scientists to use the name or cite it in their scientific work.

That makes for a potentially very confusing situation.

Confusion is not bad by itself, if the momentary confusion of scientists today helps to serve greater accuracy in the long run. But the situation with Au. prometheus is more difficult than most other shifting names. Most scientists who use the name are referring to Little Foot, and the broader uncertainty about the number of species represented at Sterkfontein. But the name belongs to MLD 1, a fragment from Makapansgat, which is a different hominin site.

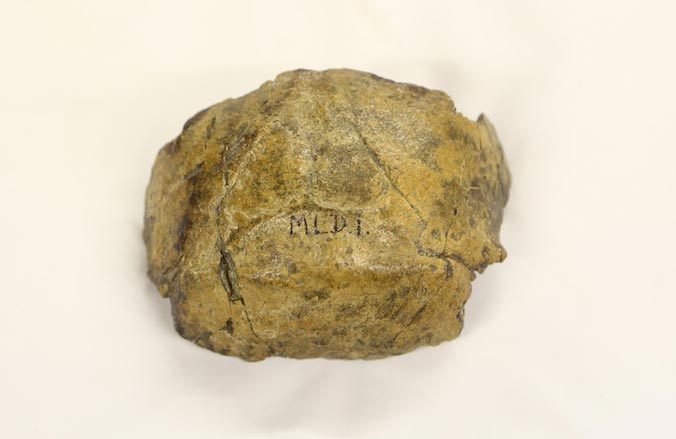

Wait, MLD 1? Isn't that just a tiny fragment?

MLD 1 is a small piece of cranium that includes part of the occipital bone and small portions of the left and right parietal bones. Here’s the specimen:

The anatomy is not very informative.

In his description of the specimen, Dart noted several features. Many of them distinguish the fragment as a hominin as different from the non-hominin great apes. The informative features that were in Dart’s view different from other early hominin specimens were extremely limited.

In his comparisons, he emphasized three comparative samples. One was the set of remains that we today would call Homo erectus, and at the time were known as Sinanthropus from Zhoukoudian, China, and Pithecanthropus from Trinil and Sangiran, Java. The Zhoukoudian remains had been described in detail by Franz Weidenreich in a series of monographs that influenced Dart’s approach to the Makapansgat specimen. The second set of remains was from Sterkfontein, where Robert Broom had uncovered a number of fossil skull remains of a hominin he called Plesianthropus transvaalensis. Today we know most of these Sterkfontein fossils as Au. africanus.

The last comparative sample was the specimen Dart had described in 1925, the Taung specimen of Au. africanus This was the critical one, but unfortunately there was very little that could be compared between Taung and MLD 1 aside from their size: The Taung specimen does not preserve the portions of occipital or parietal bones that are present in MLD 1.

In Dart’s view, the inion (highest central point of attachment of the nuchal muscles) was lower on the MLD 1 specimen than in Sinanthropus or Pithecanthropus. In Dart’s interpretation, the anatomy of Australopithecus was “diametrically opposed to the apes and is much closer to modern man than are Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus. In other words, he argued that the South African Australopithecus was more humanlike than the Asian fossils.

Yet the MLD 1 nuchal plane was longer than in the newly-discovered Plesianthropus skull from Sterkfontein, Sts 5. This would make Plesianthropus even more humanlike than Australopithecus, by Dart’s argument. He escaped this conclusion by arguing that the small brain size of Plesianthropus and more developed occipital torus gave its posterior cranium more of a Sinanthropus profile. Australopithecus was in Dart’s opinion the really humanlike form; the others were specializations that had no close connection to humans.

The lambdoidal suture of the MLD 1 specimen has a number of “Wormian bones”, which are independent centers of ossification within the suture boundary separating the occipital and parietal bones. This is not a unique feature – many humans and great apes have such complex sutures, and they do not distinguish species from each other. Dart recognized that Sinanthropus specimens had similar form, and suggested that this feature might reflect more variable ossification and delayed suture closure in the evolving brain of Australopithecus.

Finally, Dart suggested that the cranial capacity of the specimen had been fairly large compared to the Sterkfontein endocasts. He explicitly identified this large brain size as a similarity with the Taung specimen, writing:

The endocranial volume (520 cm3) of the 6-year old Taungs infant postulated an adult endocranial volume equivalent to that of the Makapansgat adult; the endocranial cast of this adult occiput confirms and corroborates the evidence of cerebral expansion and intellectual superiority furnished over 20 years ago by the Taungs endocranial cast.

(I note here that Dart’s estimates, both for MLD 1 and for Taung, were too large by a substantial extent. He discusses a similar overestimate of the brain size of Paranthropus robustus from Kromdraai in the paper. Basically, Dart seemed attached to any trait that would make Australopithecus look more humanlike than Plesianthropus.)

In anatomical terms, this is very little to go on. No traits that Dart observed could separate the MLD 1 fragment from the Taung specimen of Au. africanus.

But Dart believed that the Makapansgat site represented a very different context from Taung. At Taung, where he had identified Au. africanus, the other fossils were rich in monkeys and small mammals but poor in large mammals like antelopes. Makapansgat had a rich array of antelopes and other large mammals, and some of the bones were blackened in color. Dart came to believe that the bone bed at Makapansgat was a “kitchen midden”, with the broken-up bones of prey animals of hominins that had been cooked in fires.

Dart argued that his interpretation of behavior by these hominins justified the new species name, Au. prometheus.

Wait, really? The occipital bone fragment was supposed to have come from a different species because it ate animals and used fire?

Basically, yes. Dart became convinced that Makapansgat provided unique evidence of behavior by Australopithecus. He imagined the bones of antelopes and other large mammals at the site to be the prey of the hominins. In the 1948 paper, he wrote:

The special significance of the Makapansgat valley limeworks deposits in unravelling these early human mysteries lies in their being true hearths and thus providing information, that hitherto has been lacking elsewhere in South Africa, concerning man’s hunting skill, his probable weapons and his use of fire.

Dart developed this opinion long before any hominin fossils were known from Makapansgat. Wilfred Eitzman, a high school teacher, first sent Dart fragmented animal fossil bone from Makapansgat in 1925. Some of those bones were darkly stained, and Dart provided samples to chemists who suggested that the black particles were evidence of free carbon, which might have been produced by fire. Dart described this in a short 1925 paper.

Later in his life, Dart would write that in 1925, he had assumed that the bones had been fragmented by ancient humans, not anything as small as the Australopithecus he identified at Taung.

Twenty years later, starting in 1945, students from Dart’s anatomy department began to explore for fossils at Makapansgat and other nearby sites. Led by the young Phillip Tobias, the students conducted a series of field expeditions. In the course of this work they uncovered a number of fossil baboons, which Robert Broom confirmed to be of substantial antiquity. These baboon fossils convinced Dart that the fossil deposits were older than he had once assumed, and instead of prehistoric humans, he now hypothesized that Australopithecus might be found there.

In 1947, one of the students—James Kitching, who went on to a stellar career in paleontology—found a piece of hominin occipital bone. This first hominin discovery, numbered MLD 1, would become the type specimen of Au. prometheus when Dart described it in 1948.

But earlier, in 1946, an episode occurs that helps to show just how prometheus-minded Dart really was. Tobias told the story in his 1997 retrospective on Makapansgat:

We handed over to Dart and [Lawrence] Wells a number of primate crania, among other fossils from the Limeworks. One day, Dart came into the Medical B.Sc. Laboratory with a beatific expression on his face and, without saying a word, walked around the room shaking hands with each one of us who had been on the expedition. Then he stated simply, "Congratulations. You have discovered the Makapansgat apeman." He had identified one of our primate skulls as that of an australopithecine! As leader of the expedition I was privileged to be allowed into the technical laboratory two doors away, where, under powerful lights, the telltale specimen was being photographed. Dart had already sent a note to Nature in which he announced the discovery of the first hominid from Makapansgat. Mindful of the earlier finding of blackened bones there, which, following laboratory tests by Moir and Fox, he had interpreted as having been darkened by fire, he had even named the new hominid, Australopithecus prometheus (Dart & Craig 1959, p.51).

...

The name had been created, the paper had gone off, and it remained only for the photographs to be taken and sent to Nature. There, in the laboratory, the specimen was posed, the lights were adjusted, the camera was poised - when I saw Lawrie Wells, his head on one side, frowning slightly. He then turned his head the other way and frowned more deeply. In a small voice, he said, "Professor, if you look at it this way, it looks like the skull of a baboon." Indeed that is what it turned out to be! The note to Nature was withdrawn, feelings were doubtless bruised, the name was left hanging fire, as one might say, and Wells's powers of observation and his morphological skills had won the day. When two years later James Kitching recovered a genuine australopithecine at the Limeworks (Figure 8), Dart resurrected the same name (Dart 1948).

This is a remarkable story, even if Tobias embellished it. Dart had evidently convinced himself that the Makapansgat site would hold a new hominin species, before any fossils were found. He was ready to name it prometheus, no matter what it looked like.

Dart’s preconceptions about the Makapansgat site are not directly relevant to whether scientists should recognize the species he named. What matters is the article he wrote to describe MLD 1.

That article didn’t focus on anatomy that might distinguish MLD 1 from the Taung specimen. This story about the baboon fossils does help to explain some of the deficiencies of that later article. Dart was ready to go based upon his interpretation of the animal bones at the site. The anatomy of the specimen itself simply did not distinguish it from Au. africanus as Dart knew it.

Did Dart have in mind something like the "killer ape"?

The idea of Australopithecus prometheus had tremendous impact on scientists and society outside human origins research.

Over the next decade, Dart developed his idea of the “Osteodontokeratic culture”. In the broken animal bones from Makapansgat, Dart saw killing weapons. He embraced the idea that hunting made apes into humans by causing them to confront other animals. For example, in a paper titled, “The predatory transition from ape to man”, Dart wrote:

On this thesis man's predecessors differed from living apes in being confirmed killers: carnivorous creatures that seized living quarries by violence, battered them to death, tore apart their broken bodies, dismembered them limb from limb, slaking their ravenous thirst with the hot blood of victims and greedily devouring livid writhing flesh.

If this sounds familiar, it may be because it inspired Stanley Kubrick’s image of violent, bone-shattering apemen at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Dart had a vivid imagination for the behavior of prehistoric hominins. Most of his ideas about ancient behavior turned out to be wrong. It would take the development of the science of taphonomy to prove that Dart’s ideas don’t fit the facts. The animal bones from Makapansgat had been broken by natural processes. The hominins did not break up the bones or bash into them at this site. The blackened coloration was natural manganese deposition, common in the dolomite caves of South Africa.

The killer ape was pure imagination.

What is a nomen nudum?

The rules of naming animal species and other animal groups were set down by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, starting in 1895. Those rules constitute the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, and the Code has been updated periodically over the years to formalize and standardize practices used in the taxonomy of various groups. Hominins are animals, and so the names of fossil hominins fall under the Code.

A nomen nudum is a name that was never provided with a valid diagnosis under the Code.

People make up fictional and imaginative species names all the time. Some of these are famous in the study of human evolution.

For example, the nineteenth-century German biologist Ernst Haeckel named the fictitious species, Pithecanthropus alalus to represent his hypothetical ancestor of humans, one “missing link” in the evolutionary chain. When Eugene Dubois later discovered the hominin fossil skullcap from Trinil, Java, he named it Pithecanthropus erectus. Dubois transformed Haeckel’s fantasy name into a real species.

Lee and I looked very carefully at the details of Dart’s description. Peer referees also helped us to see some aspects that had greater importance than we initially thought. At the end, after reviewing the history of Au. prometheus and Raymond Dart’s original definition from 1948, we are able to show that the species was never properly defined.

It can be hard to go back to older sources and figure out which parts of the text are relevant to the rules of taxonomy. But while the Code has changed somewhat over time, they have always guided the way scientists must interpret formal descriptions of papers. Dart’s definition had to follow the Code, and we can interpret it in terms of the Code today.

When looking at the original paper describing MLD 1, we saw that Dart never provided features that could distinguish Au. prometheus from Au. africanus. Dart was a world-recognized anatomist. But he faced an insoluble problem: Au. africanus to him was only represented by the Taung specimen. And Dart was convinced that the two specimens were the same form, with slight differences due to the sites they were from. He continually emphasized the similarities between these, but was left without any diagnostic differences.

Today most scientists recognize a large sample of fossils from Sterkfontein as Au. africanus. But by 1948, Broom had only uncovered a few of these fossils, and had formally assigned them to the species that Broom had diagnosed at the site: Plesianthropus transvaalensis. Dart describes a few differences between the MLD 1 specimen and Plesianthropus. None of these distinguish the fossil from the juvenile Taung skull. Dart emphasizes throughout his paper that the MLD 1 specimen is the adult form of Australopithecus, while the Taung skull is the juvenile. He uses the features by which MLD 1 differs from Plesianthropus as ammunition for his argument that Australopithecus is more humanlike.

All of this is interesting to the history of anthropology. But none of Dart’s accurate description of the specimen did what a formal taxonomic definition must do: scientifically distinguish Au. prometheus from Au. africanus.

Dart did recognize the “complex sutural system” of the MLD 1 specimen as a possible difference from Au. africanus. But he clearly notes that such a trait might not be enough to distinguish the species, and it is obvious that the Taung specimen doesn’t preserve enough evidence to make this comparison.

In the place of anatomical features, Dart based his definition of Au. prometheus upon his interpretation of the behavioral evidence from Makapansgat. He imagined the Makapangat australopithecine as a predator. Dart’s idea that Au. prometheus is different from Au. africanuswas based upon his interpretation of the site, not the features of the specimen.

That definition simply does not satisfy the requirements of the Code. Finding that a skull fragment is associated with broken antelope bones is not a feature that distinguishes a species from any other fossil found in different circumstances. And so under the rules of the Code, we argue that Au. prometheus should be recognized as a nomen nudum.

A nomen nudum cannot be validly used in comparisons with other species. But that doesn’t have to be the end of the story: There is a procedure to revive such a name. A scientist can provide a new scientific definition for a nomen nudum that satisfies the Code, and can petition the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to recognize a new holotype specimen.

Since Au. prometheus is based on a fragment, why is it not a nomen dubium?

Biologists also have named species based on specimens that are too fragmentary or incomplete to compare any other specimens. Such a name under the Code is known as a nomen dubium: a “doubtful name”.

In my opinion, the hominin fossil record is full of such nomina dubia. The holotype specimens of many hominin species are no more than fragments. They don’t give enough information to evaluate whether other, more complete specimens are the same or different. That makes any attribution of another specimen to such species untestable.

A good example of the problems caused by such nomina dubia is Homo heidelbergensis. The holotype of this species is a mandible recovered from Mauer, Germany in 1907. It is a beautiful specimen, and it is unusual in comparison to mandibles from other Middle Pleistocene European sites. For much of the twentieth century, it was forgotten. But starting in the 1990s, some specialists in human evolution began to revive Homo heidelbergensis. Some argued that skulls from Africa, even China, might be attributed to the species, as a common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals. Others saw the species name as a catch-all for Middle Pleistocene remains from Europe, so-called “pre-Neanderthals”. The richest site in the human fossil record, Sima de los Huesos, was argued by many anthropologists to represent Homo heidelbergensis, despite some obvious differences between the Mauer specimen and any of the Sima de los Huesos mandibles.

In short, anthropologists pursued ideas of Homo heidelbergensis that were based their ideas of how hominin species evolved over time and space, not the anatomy of the holotype.

Anthropologists unfortunately sometimes become attached to a nomen dubium. But they cannot be scientifically tested. It would improve the science of human evolution to recognize that such names are nomina dubia and stop citing and using them.

On the surface, Au. prometheus seems to fit this definition. Scientists have known that the MLD 1 specimen is too fragmentary to provide valid comparisons with most other hominin fossils, ever since the specimen was discovered. The specimen includes only part of the occipital bone and small parts of the two parietal bones. A name attributed to such a fragment under the Code would often be called a nomen dubium.

But when Lee and I examined the situation of Au. prometheus, we came to a different conclusion. Dart’s definition of Au. prometheus never distinguished MLD 1 from Au. africanus in the first place. Without such a diagnosis, Au. prometheus is better understood to be a nomen nudum.

We recognize and discuss in our paper the alternative that many scientists will prefer to see Au. prometheus as a nomen dubium. Under the Code, a nomen dubium can never be revived by providing a new definition. Such names are dead to taxonomy.

Aren't all species names from that era mostly fluff, anyway?

The New Synthesis in evolutionary biology during the 1930s and 1940s had as one of its consequences a revolution in practices in systematics. Earlier practice had named many more species and genera in some animal families. The hominins in particular had become a morass of genus and species names.

In a famous contribution to the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology published in 1950, the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr proposed a massive simplification of the classification of hominins. Instead of nigh-on a dozen genera and species, he suggested recognizing only three successive species. For all the australopithecines, he suggested lumping into the single species Homo transvaalensis.

This was the conversation among evolutionary biologists just as Dart was naming Au. prometheus. Dart’s Australopithecus would be completely wiped out if anthropologists had accepted Mayr’s idea. So you might imagine Dart was using an old-fashioned style of naming species, and the modern way would give rise to something else.

But it is too simple to see this as two different styles of naming species.

When you read Dart’s 1948 article on the MLD 1 occipital bone, you can see that he was working toward seeing the fossil hominins from these sites as biological species instead of mere names. His logic was based on behavior and geology, not on small details of anatomy of MLD 1. Reading through his paper, I get the impression of someone thinking about the whole organism, and what kind of variation should correspond to species and genus differences.

And Dart very quickly agreed with Robinson (1954) who proposed a simplification of the South African hominin classification. Robinson’s ideas were not as extreme as Mayr’s, and in fact what most anthropologists accept today is based largely on Robinson’s concepts of species. It was very easy for Dart to slightly modify his perspective on species by abandoning the name Au. prometheus and recognizing that the Makapansgat and Sterkfontein samples have “no more than racial differences.”

The problem with Au. prometheus, in other words, is not that Dart’s view of species was antiquated. It’s just that MLD 1 could not support a definition that distinguished it from Au. africanus.

What about the other hominin fossils from Makapansgat? Don't they help round out the anatomy Dart described?

Over fifteen years after 1948, teams working at Makapansgat found more hominin fossils. Initially, Dart attributed these to Au. prometheus, following his idea that “this locality, and the novel evidence it affords” were the important things for deciding to which hominin these fossils belonged.

Dart conceived of the difference between sites as the key difference justifying different species. In his interpretation, Taung and Makapansgat preserved different evidence of behavior, and so they must have been inhabited by different species.

Robinson’s 1954 taxonomic reinterpretation made it clear that no features reliably separated Makapansgat fossils from Sterkfontein fossils. Dart quickly came to agree with Robinson. Traits do not reliably separate the Makapansgat and Sterkfontein samples. Since the 1950s, nobody has thought that each of these two sites represents a different species, one from Sterkfontein and one from Makapansgat.

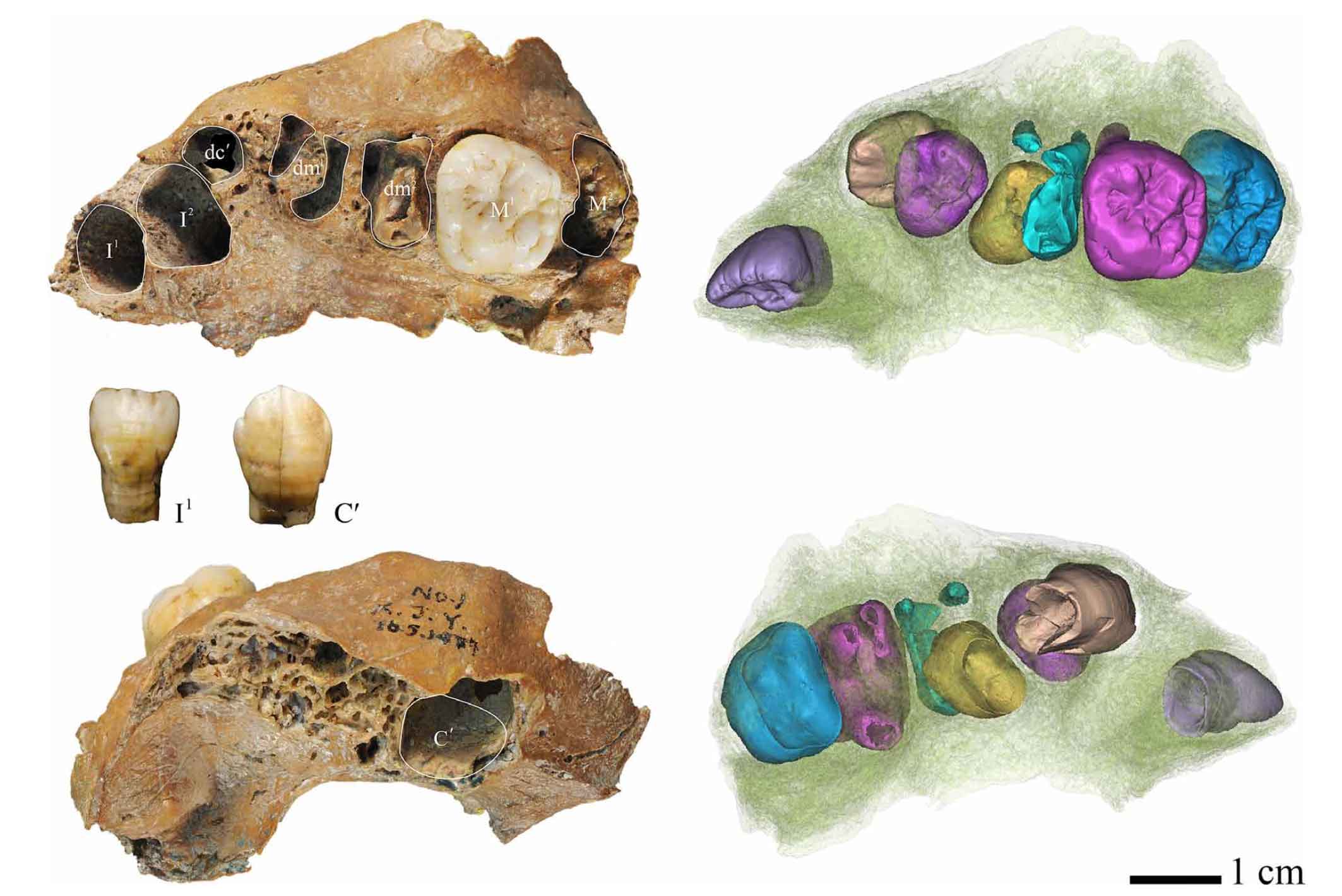

A few, including Clarke, have suggested that each site might by itself have two or more species; for example Ron Clarke has suggested that “robust” specimens at Makapansgat like MLD 2 were part of Au. prometheus but not more gracile ones like MLD 6.

But Clarke, like everyone else, accepts that no other Makapansgat specimen matters to the name that applies to this grouping. Only MLD 1 matters. And if the Makapansgat hominin sample is a heterogeneous collection of two (or more) different species, there is certainly no basis for saying that any of the other specimens are necessarily the same as MLD 1.

It is not valid to take traits from other specimens, such as the MLD 2 jaw, and assume those belong to Au. prometheus. The traits of MLD 1 do not support assigning it to either species over the other, if there were two of them.

Is it true that Dart abandoned Au. prometheus?

I cannot make this any clearer than these quotes from Dart himself:

The Makapansgat female skull is slightly wider and lower than the Sterkfontein female but because of their obvious similarities and their proximity in many respects, which will be demonstrated in a subsequent communication, I do not regard them as specifically distinct from one another zoologically any longer. (Dart, 1962a: 125, emphasis added)

While these differences appear to characterize the male as well as the female australopithecines at Makapansgat there seems to be no justification now for regarding them or any other known differences between the Sterkfontein and Makapansgat australopithecines as having more than variety value. (Dart, 1962a: 126, emphasis added)

There is therefore no good reason for separating the Makapansgat from the Sterkfontein australopithecine specifically; from the mandibular point of view they probably present no more than racial differences. (Dart, 1962b: 285)

Is there now a new definition for Au. prometheus?

Ron Clarke and Kathy Kuman extensively discuss Au. prometheus in their new preprint, just released last month. The preprint assigns the StW 573 skeleton to Au. prometheus. The preprint also provides a paragraph-long definition for both this species and Au. africanus, which differentiates these species from each other.

Sadly, the definition provided by Clarke and Kuman isn’t enough to correct the deficiencies of Dart’s original definition.

Dart’s definition applied the name Au. prometheus to a fossil specimen, MLD 1, that is different from Little Foot in the tiny handful of characters that can be compared between them.

For example, Clarke and Kuman suggest that Au. prometheus has an endocranial volume above 500 cc, and Au. africanus has an endocranial volume below 500 cc. This is the first element of their definition.

The idea comports with Dart’s original idea about the cranial capacity of MLD 1, which he thought was above 600 cc. Today few anthropologists would go so far, but Clarke has emphasized that the remaining parietal portions of MLD 1 suggest that the sides of the skull were more vertical and reflect a larger endocranial volume than in Au. africanus skulls like Sts 5.

But the Little Foot endocast is much smaller than this. The new paper describing the endocast by Amélie Beaudet and colleagues finds its volume to be only 408 cc, which the note plots “at the lower end of Australopithecus variation”. This is a minimum estimate that does not attempt to correct the distortion in the skull, but it is quite far from what Clarke and Kuman define as the minimum size of Au. prometheus. A reconstruction would have to inflate the endocast by 25% to fit Clarke and Kuman’s definition, and Beaudet and coworkers do not describe that degree of distortion. No matter what, this is a very clear difference that the StW 573 specimen shows from Clarke and Kuman’s definition of Au. prometheus.

I don’t know why Clarke and Kuman chose to make the first feature in their Au. prometheusdefinition one that clearly excludes Little Foot. They had 20 years to work on this, and yet they haven’t been able to come up with a definition of Au. prometheus that includes this nearly complete skeleton.

Another clear difference between Little Foot and MLD 1 is the form of the lambdoidal suture. This was the only anatomical trait that Dart listed as possibly differing between Au. prometheusand Au. africanus in his definition. This was not correct science, as the form of this suture is variable in hominin species and should not bear any weight in defining a species. But it is noteworthy that the Little Foot skull differs strongly from the type specimen of Au. prometheusin this trait. MLD 1 has a complicated suture with several Wormian bones. StW 573 has a simple suture.

In my opinion MLD 1 is a tiny fragment that doesn’t have enough information to validly compare to a complete skeleton. Relying upon such a fragmentary specimen is a very bad idea. No matter what is concluded from such a fragment, it will be subject to unending controversy.

But does Sterkfontein have two species?

Lee and I express no opinion about this in our new paper. Personally, I think this is a very challenging hypothesis to test in the Sterkfontein sample, and doing so will require a close comparison of all the specimens with variation in other hominin samples. That hasn’t been done.

Can Au. prometheus be revived?

If our opinion is accepted, and Au. prometheus is a nomen nudum that was never properly defined, then someone could revive it by following the rules. A future scientist could propose a new holotype specimen by formal application to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

That’s sure to be a difficult process, since the history of this species is complicated. The recent attempts to resuscitate it haven’t helped. And the dark history of the “killer ape” hypothesis provides a pretty good reason to come up with some other name instead. But it’s possible.

Instead of a nomen nudum, some scientists would probably argue that Au. prometheus is formally a nomen dubium. This is often used for species where the holotype specimen is too fragmentary to judge whether other specimens belong to the same species or not. Lee and I think this doesn’t fit because Dart failed to distinguish the species from Au. africanus in the first place. But I don’t think either of us would be surprised if other scientists favored the dubiumidea.

If it were accepted that Au. prometheus is a nomen dubium, then there is no bringing it back. The name will always stick with the MLD 1 holotype, and that specimen will be forever doubtful.

The thing is, if Makapansgat, Sterkfontein, and Taung only have a single species between them, then that species is Au. africanus. If the Taung specimen stands apart, and Makapansgat and Sterkfontein represent a second species, then that species is Au. transvaalensis, because Plesianthropus transvaalensis was named before Au. prometheus. Only if Sterkfontein and Makapansgat have two or more species among them can Au. prometheus come into play. And if there are two species there, the MLD 1 specimen does not preserve enough anatomy to tell which it is.

That’s a nomen dubium scenario, and it’s one from which Au. prometheus will never resurface.

References

Beaudet, A., Clarke, R. J., de Jager, E. J., Bruxelles, L., Carlson, K. J., Crompton, R., ... & Jashashvili, T. (2019). The endocast of StW 573 (“Little Foot”) and hominin brain evolution. Journal of Human Evolution, 126, 112-123.

Clarke, R. J., & Kuman, K. (2018). The skull of StW 573, a 3.67 Ma Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. bioRxiv, 483495. doi:10.1101/483495

Dart, R. A. (1948). The Makapansgat proto‐human Australopithecus prometheus. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 6(3), 259-284.

Dart, R. A. (1953). The predatory transition from ape to man. International Anthropological and Linguistic Review, 1, 201-218.

Robinson, J. T. (1954). The genera and species of the Australopithecinae. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 12(2), 181-200.

Tobias, P. V. (1997). Some little known chapters in the early history of the Makapansgat fossil hominid site. Paleontologica Africana, 33, 67-79.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.