Why are humans evolving to lack their wisdom teeth?

The frequency of M3 agenesis varies greatly among human populations. It may have to do with agricultural diets, but anthropologists aren't sure.

One of the most profound cases of recent human evolution is the increasing frequency with which individuals don’t develop third molars, what is called “M3 agenesis”. This condition is when the third molars, or wisdom teeth, don’t form at all—the individual never developed them.

There are a few instances of M3 agenesis in hominins outside of modern humans. Two individuals attributed to Homo erectus, Dmanisi D2735 and KNM-WT 15000, both seem to be cases, as is the LB1 individual of Homo floresiensis. But outside of these few, most hominins throughout our evolutionary history developed and erupted third molars into normal occlusion.

Agenesis of the third molars is different from cases where the M3 fails to erupt normally or remains impacted within the jaw. It is also different from the dental or surgical removal of third molars, which is now carried out on a very high proportion of people in the United States and many other countries. The number of students in my courses at the University of Wisconsin that still have their third molars is pretty small, generally less than 20 percent and often less than 10 percent. The majority of third molar removal is for orthodontic purposes. When third molars erupt, they exert forces on the rest of the teeth that can cause crowding and malocclusion, and more rarely, severe pain. One of the easiest ways to maintain straight teeth is to extract the teeth that are farthest toward the back.

The problems with crowding of the anterior teeth points to the reason that anthropologists have traditionally given for the change toward a higher incidence of agenesis. Our Pleistocene ancestors very rarely had malocclusions due to dental crowding. The development of our jaws and teeth evolved within a context where people lived hunter-gatherer lifestyles and ate fairly tough foods, even as young children. By contrast, crowding of the dentition and resulting malocclusion have been very common in many Holocene populations, mostly those with agricultural subsistence. Agriculturalists don’t eat as many tough foods; they eat a large fraction of cooked grains and easy-to-chew cooked plants, milk, and meats. The idea is that the development of the jaw is plastic, and a reduction of the forces exerted on the dentition during early childhood can alter the developmental trajectory of the mandible and maxilla. If the jaws don’t develop as to as large an adult size, the teeth will tend to be crowded, and the last teeth to initiate development, the third molars, may not form at all.

This is an elegant story in some ways, but we don’t really know whether it’s true.

We do know that the teeth develop from an embryonic tissue sheet, which is divided into segments by genes during early development. Those segments expand and wrinkle into the form of tooth germs in a characteristic pattern, which is retained across most mammal orders, although many of the orders have come to have different numbers of teeth, which result from evolution of this early developmental pattern. Within a species, if an individual ends up with a segment that is too small or doesn’t develop quite right, that tooth will not form. The most common change is to the extreme tooth, which is the third molar. Less commonly, individual teeth within the other types may fail to develop. P4 agenesis is fairly frequent, sometimes the I2 doesn't develop. Some of these kinds of agenesis are syndromic, meaning that other biological traits covary strongly with them.

Anthropologists don't fully understand how jaw forces might influence the pattern of tooth development. Nor is it well understood how heritable M3 agenesis may be. It does tend to run in families, but it's not clear yet how much this reflects similar environments versus similar genetics.

We do know quite a bit about the incidence of M3 agenesis in different human populations. The trait is nearly universal. It occurs everywhere in large enough samples of people, even in hunter-gatherer peoples who have recently continued eating “wild” food diets. But it differs greatly in frequencies.

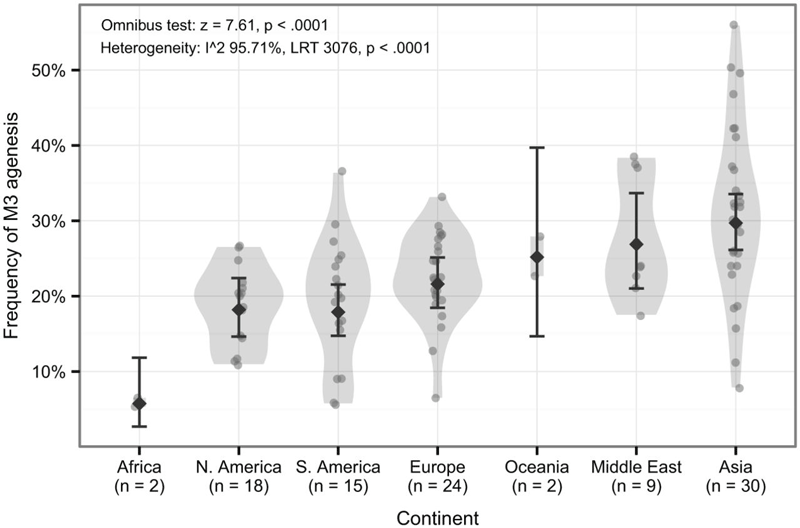

Carter and Worthington (2015) did a meta-analysis of studies that have estimated M3 agenesis frequencies in particular human populations. By looking at 92 studies in different regions of the world, they give a global picture of where humans are more or less likely to have agenesis of the third molars. They limited their analysis to include studies of living human populations with radiographic evidence, so the agenesis was clearly documented.

Here’s the picture summarizing the frequencies in different regions:

The incidence of M3 agenesis is lowest in African populations today. This chart represents only two studies in Africans, but the observation of a very low frequency of M3 agenesis is in accord with studies of skeletal samples in my experience. Other populations have a higher frequency, although the study does not include any populations indigenous to Australia, New Guinea or the nearby areas of Melanesia, which in my experience also have low frequencies of M3 agenesis. Some of the highest population frequencies are observed in Asia; these are sampled broadly, including one sample from South India, several studies of Japanese, Turkish, Israeli and Iraqi. So it’s not specifically East Asian, but more broadly some population samples across the continent.

The most common M3 agenesis is a single missing third molar, and that is what is illustrated in the chart. It is less common to be missing two molars, and very uncommon to be missing three or all four of them. Women are slightly more likely to be missing an M3 than men (Carter and Worthington found a 14 percent greater likelihood in women).

I know that many anthropologists lecture about M3 agenesis as a recent evolutionary change, but it is a complicated one. Few look deeply into the pattern, which is strongly parallel across many human populations, not regionalized. In a broad sense, the frequencies of M3 agenesis across populations covary with molar sizes, and it may simply be that the evolution of smaller tooth size has M3 agenesis as a frequent side effect. The greater incidence of agenesis in women also might be expected as a correlate of smaller molar sizes.

There is no evidence that M3 agenesis is itself an adaptation that has been favored by natural or sexual selection. The possibility of sexual selection presents itself in this context because of the possible effects of a crowded dentition on mating preferences in past populations. But if M3 agenesis owes its recent high frequency to selection, it is likely as a side effect of selection for smaller teeth. However, even that is hardly so simple, as the pattern of size reduction in teeth was not uniform in Holocene populations, and the frequencies of M3 agenesis fluctuate substantially among studies.

And we do not know how much of M3 agenesis may be explained by plasticity of development within current environments. Some studies show a difference within a geographic sample between people who have originated from different immigrant populations (for example, in Singapore between people of Chinese, Malay, and Indian ethnicity), but none have really evaluated the frequencies in second-generation and third-generation immigrants. The genetics of the trait, even heritability, is basically an open question. Of course, if it were entirely explained by environment, M3 agenesis would not be an example of evolutionary change at all.

So M3 agenesis is a fascinating example of recent biological change in human populations, and we know very little about how and why it has changed.

Reference

Carter, K., & Worthington, S. (2015). Morphologic and Demographic Predictors of Third Molar Agenesis A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of dental research, 94(7), 886-894. doi:10.1177/0022034515581644

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.