Another Denisovan from Denisova Cave

A review of the 2015 work identifying the Denisova 8 specimen by Susanna Sawyer and coworkers.

Denisova Cave is one of the most fascinating places in the story of human origins. The cave is in the northern wall of the Anuy River valley, within the Altai Krai region of Russia but very near the border with the Altai Republic.

The cave’s East Gallery, where excavators still work through part of the Altai summer, feels like a walk-in refrigerator. Archaeologists work inside wearing rugged jackets as they work slowly down through sediments at five degrees Celsius. In the winter, the temperature inside the cave is below freezing. The exceptional cold has made this cave into a time capsule for ancient genetic sequences.

The fossil hominins from the cave are mere scraps, some of them possibly leftovers from hyena meals. But before now three of the bones and teeth have produced genetic sequences, including two from a previously-unknown population that we now call the “Denisovans”.

Today there’s something new. Another hominin tooth, Denisova 8, has now yielded a partial low-coverage genome, and we can welcome it as a new member of the Denisovan population. Its DNA sequence shows that this tooth is older than the other Denisovan specimens, maybe 60,000 years older. And its DNA increases the diversity of the known sample of Denisovan specimens.

What’s important about this? And how does it fit into the already-complicated Denisova family?

The Denisova cast of characters

The story of the hominins from this cave has been fast-moving for the last five years. If you haven’t been following closely, it probably seems like a telenovella. Many characters jump out for attention, each with a special, distinctive story.

The first and most famous of the specimens is the distal phalanx from a fifth finger, Denisova 3. When ancient mitochondrial DNA from Denisova 3 was first reported in 2010 by Johannes Krause and colleagues, they found it was very different from any known human or Neandertal—so different that they called this hominin the “X-Woman”.

That name didn’t last long. Later in 2010, David Reich and colleagues followed up on the mtDNA by sequencing a low-coverage nuclear genome from the specimen. They showed that even though the mtDNA of Denisova 3 last shared an ancestor with us more than a million years ago, the nuclear genome is much less divergent. The “Denisovan” really did belong to a previously unknown population, very different from living humans. But it shared an ancestry with Neandertals within the last half million years.

At the same time, Reich and colleagues sampled the mtDNA from a second hominin specimen. This one, Denisova 4, is a third molar, or “wisdom tooth” representing a different individual from the finger bone. The mtDNA of this tooth is not identical to the finger, but it does belong to the same highly divergent lineage.

In 2012, Mattias Meyer and colleagues did more work on the Denisova 3 sample, ultimately yielding a very high coverage genome. From this genome it was possible to show that Denisova 3 came from a very endogamous population, one that had been small for a very long time.

Then, in 2014, Kay Prüfer and colleagues sequenced the DNA from another Denisova Cave specimen. This one, a toe bone, came from a similar archaeological level as the original Denisova 3 sequence, although it lay a bit lower in the sequence and therefore is probably a bit older. This toe bone produced another high-coverage genome, the second from the site. And unlike the other two Denisova specimens, this toe belonged to a Neandertal.

That’s quite a trick, telling Neandertals from previously unknown populations based on fingers and toes. Anthropologists would never attempt such a thing from the bones themselves. Or, maybe more accurately, some anthropologists would make extravagant claims from the finger and toe bones, and they would be fools.

But a whole genome gives millions of bits of evidence about relationships. The two Denisova mtDNA sequences stand apart from any known Neandertal or modern human. The nuclear genome of Denisova 3 differs from any known Neandertal or modern human at millions of base pairs. Still, that Denisova 3 genome has large stretches of DNA shared with the Neandertal toe bone, indicating that the Neandertal population interbred with the ancestors of the Denisovan individuals at some point.

And the Neandertal toe bone itself was highly inbred—as homozygous across its whole genome as people whose parents are half-siblings.

It’s a Paleolithic telenovella.

Denisova 8

Now, Susanna Sawyer and colleagues report this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the genetic data from a third Denisovan individual, Denisova 8. And they add nuclear genetic sequence, at low coverage, from the Denisova 4 tooth.

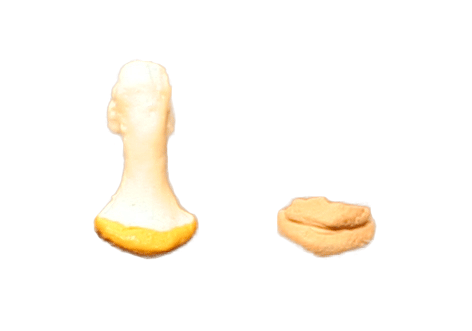

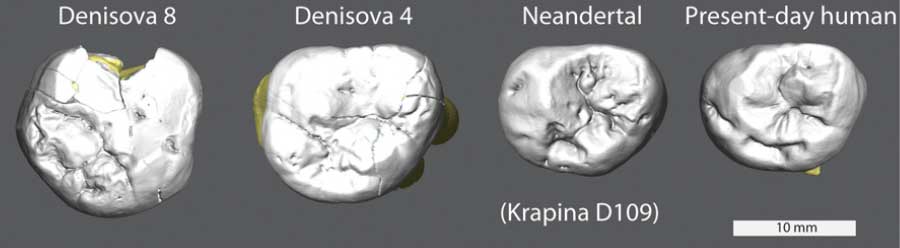

Denisova 8 is another tooth, again, likely a third molar. The two teeth are morphologically different from each other, with little indication that they reflect a single gene pool, except that the teeth are both quite large relative to most later Pleistocene humans.

One of the main genetic results is that the two molars (Denisova 4 and 8) clearly group with the original pinky (Denisova 3) genome in their nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. However, Denisova 8 is an outlier to the other two, more different from them in mtDNA sequence than any Neandertals are from each other, and somewhat more different in the nuclear genome than would be typical for Neandertals.

Part of that difference is due to the age of Denisova 8. Its mtDNA branch is shorter than the other two specimens. It is missing evolutionary history that is present in Denisova 3 and Denisova 4, enough to suggest that Denisova 8 lived some 60,000 years earlier in time than those other two. The nuclear genome is consistent with such an age estimate, although the low-coverage sequence is not really sufficient to give an any accuracy on its own. So one reason why Denisova 8 increases the diversity of the Denisova sample is that it lacks tens of thousands of years of genetic drift that was shared in the ancestry of the later specimens.

Still, when we look at the variation in the two low-coverage genomes from Denisova 4 and 8 in comparison with the high-coverage Denisova 3 genome, all the Denisovans together seem to have been just a bit less inbred than Neandertals. Sawyer and colleagues provide a measure of genetic difference between genomes that is scaled to the difference between humans and chimpanzees. To accomplish this measurement, they take the preserved sequence that overlaps between two low-coverage genomes (or high-coverage genomes), examine every site within the overlapping sequence where either of the two hominin sequences differs from the chimpanzee genome, and examine the fraction of times that the two hominin sequences are discrepant from each other. This gives a measure of difference between the two genomes relative to their difference from chimpanzees.

For the Denisovan genomes, this difference averages 2.9 percent. For Neandertal genomes compared to each other, the difference averages 2.5 percent. So Denisovans are a bit more diverse than Neandertals by this measure.

For human populations, the differences range between 4.2 and 9.5 percent. The least diverse pair of individuals are Karitiana people from South America. This highly endogamous human group is still half again as diverse as Denisovans.

Both the Denisovans and Neandertals were very endogamous relative to today’s people, even just comparing to Europeans today. That endogamy must reflect something about the ancient population structure of these archaic people. One consequence of the endogamy — as two preprints by Graham Coop’s lab and Rasmus Nielsen’s lab show — is that Neandertals may have carried a load of slightly deleterious genetic variants. When the Neandertals and Denisovans mated with the more diverse population that dispersed from Africa in the Late Pleistocene, some of these deleterious genetic variants may have been slowly weeded out of the modern human population by purifying selection.

How big were the Denisovans’ teeth?

We don’t know very much about what Denisovans may have looked like, with only a fingertip and two wisdom teeth to go on. So it’s tempting to take these slim data and make something more out of them than we probably should.

With two teeth, we at least can measure their sizes. They’re big. Bigger than most living humans, bigger than any Neandertals, as big as some third molars of Australopithecus.

We can’t make too much out of the large size of these third molars, because similarly large teeth do occasionally occur among Upper Paleolithic people. The supplementary material to Sawyer and colleagues’ paper gives a brief review, noting that the Oase 2 skull has such a large third molar, as does a tooth from a partial juvenile dentition of a probable Neandertal from Obi-Rakhmat, Uzbekistan.

Two Late Pleistocene specimens are comparably large in size, the M3s of the early Upper Paleolithic modern human Oase 2 and the M2/3 of Obi-Rakhmat 1 (14, 15). Oase 2 does not show large extra cusps, but instead strong crenulation (16). Obi-Rakhmat shows a large extra cusp, but mesially, not distally (Main text, Figure 1), and a large number of accessory cusps possibly due to gemination (17).

The Oase 2 specimen is the earliest modern human known from Europe. This is not the same individual as the Oase 1 mandible, but it may be relevant that the Oase 1 specimen had more Neandertal ancestry than any known living person, and that Neandertal ancestry was quite recent, possibly within four generations.

Is it odd that we have large third molars in some individuals in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, including the Denisovans? I think to answer this we will need a larger sample of fossil humans from other places. There is at least one Chinese third molar specimen from Xujiayao that approaches the size of these large teeth. Perhaps the Chinese specimen is a Denisovan, or maybe this is one morphological extreme that is distributed among Late Pleistocene populations.

The thing is, if there was one piece of morphological evidence I would throw away and pay no attention to above all others, it’s the morphology of the third molar. It is just enormously variable among living humans and living primates. I wouldn’t trust it to tell us about relationships of hominin groups.

OK, so maybe I would trust the third molar above the pinky finger.

UPDATE (2015-11-18): I’ve known about these results for a long time, as the authors kindly shared them with me. But I forgot that the results were also previously a part of the documentary “Sex in the Stone Age”, until I found a letter from a reader in my archives. At the time I gave some context to that report from the documentary but had little more to say.

What’s interesting about this week’s publication is that the nuclear genome and mtDNA have contrasting patterns. The genetic variation within Denisovans is best assessed across the nuclear genome, and they are low in a similar way as Neandertals.

Still, the Neandertal sample covers a very large geographic area, from Spain to the Altai. Our intuition might lead us to expect that extensive range to encompass more variation than three Denisovan individuals from a single site. But the Denisovan genomes cover a longer time than the low-coverage Neandertal genomes, and across such a time they may actually sample very different populations. If we had a Neandertal low-coverage genome as early as Denisova 8, their variation might look different.

To me, the core observation is that both these populations were highly endogamous compared to any living human groups. I’ll have a bit more to say about the mtDNA discrepancy shortly…

Reference

Sawyer S, Renaud G, Viola B, Hublin J-J, Gansauge M-T, Shunkov MV, Derevianko AP, Prüfer K, Kelso J, Pääbo S. 2015. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences from two Denisovan individuals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA (early edition) doi:10.1073/pnas.1519905112

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.