Did Acheulean hominins have long-distance obsidian trade?

I review several papers looking into the occurrence of obsidian artifacts in the Acheulean of eastern Ethiopia.

In 1987, J. Desmond Clark published a review of Acheulean archaeological occurrences in two Ethiopian field areas: “Transitions: Homo erectus and the Acheulian: the Ethiopian sites of Gadeb and the Middle Awash”. I was reading this article and was interested to run across this paragraph describing obsidian transport at a very early date:

Especially interesting also is the presence of four handaxes made from obsidian, a stone found nowhere on the South-East Plateau but with the nearest sources in the Ethiopian section of the Rift Valley, ca. 100 km to the west. This implies some form of population movement or exchange between the plateau and the rift between 1.4 and 0.7 million years B.P. Since, as yet, no earlier cultural material has been found there, it was during this time, on the Gadeb evidence, that the first occupation by hominids of the Ethiopian high plateaux took place.

I’ve been looking closely at this 1987 paper because of its title reference to Homo erectus. There are no hominin fossils from these Gadeb localities. Clark thought the various local occurrences of archaeology on the Gadeb Plateau dated between 1.4 million and 700,000 years ago, based on geological work by Williams and coworkers (1979). In the years since, no further investigations have examined these dates.

People who have been following me for a while know that I am not willing to accept accept old dates without critical examination. I am also unwilling to accept associations of hominin populations and archaeological assemblages without strong evidence. There were multiple species of hominins in Africa during the Early and Middle Pleistocene, and without some strong evidence of association, we cannot say which species was responsible for particular stone tool assemblages.

On that account I have more to write. Here I want to examine the way that standards of evidence have changed over time in stone age archaeology.

Long-distance obsidian transport was not the only claim made of the Gadeb sites that would later attract attention. Ignacio de la Torre (2011) revisited the Gadeb Acheulean assemblages to evaluate whether some of the claims could be confirmed: “The Early Stone Age lithic assemblages of Gadeb (Ethiopia) and the Developed Oldowan/early Acheulean in East Africa.”He included a list:

The Gadeb record has contributed to a variety of paleoanthro- pological discussions. For example, Clark and Kurashina (1979a) emphasized the importance of Gadeb as the earliest evidence of human occupation in high altitudes, a point also highlighted by Roche et al. (1988). The presence of some obsidian handaxes, considered to be imported from a source 100 km away (Clark and Kurashina, 1979a), has also been mentioned as early evidence of long distance transfer of raw materials (e.g., Féblot-Augustins, 1990). Documentation of burned rocks in Gadeb 8E (Barbetti et al., 1980) has been repeatedly claimed as possible early evidence for the use of fire (Gowlett et al., 1981; James, 1989; Bellomo, 1993). Likewise, the partial skeleton of a hippopotamus in Gadeb 8F was interpreted as an early case of a butchery site (Clark and Kurashina, 1979a; Clark, 1987), and referred to as such by other authors (Isaac, 1984; McBrearty, 2001). Finally, Gadeb is also known for the purported inter-stratification of Developed Oldowan and Acheulean sites throughout the sequence (Clark and Kurashina, 1979a), a claim that has been widely discussed in recent years (Stiles, 1980; Isaac, 1981; Binford, 1985; Potts, 1991; Bar-Yosef and Goren-Inbar, 1993; Schick and Toth, 1994; Kyara, 1999; de la Torre, 2008).

I added the emphases there just to reflect the importance of the site to many different topics related to Early Pleistocene hominin behavior.

Looking closely at these 1970s and 1980s era publications, it is remarkable how little documentary detail they provide. Archaeologists for forty years were citing—are still citing—all these claims from Gadeb. The early fire, the hippo butchery, the interstratification of Developed Oldowan and Acheulean, and the raw material transport have all come in to reviews of the evidence and debates about the behavior of Early Pleistocene hominins. Yet, as de la Torre reflected, the basic details were not widely available for examination.

Despite regular referencing to Gadeb in recent literature on the East African Early Stone Age, no revision of the lithic assemblages has been carried out since the original studies by Clark and Kurashina in the 1970s. In fact, the only systematic account of the Gadeb assemblages (Kurashina, 1978) was never published, and no other detailed reports of the lithics were made available.

So much in Paleolithic archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s was accepted on the authority of the researcher, especially those working in Africa. Journal articles allowed the illustration of only a tiny handful of artefacts from any assemblage, and authors tended to select illustrations that confirmed their assessment of typology.

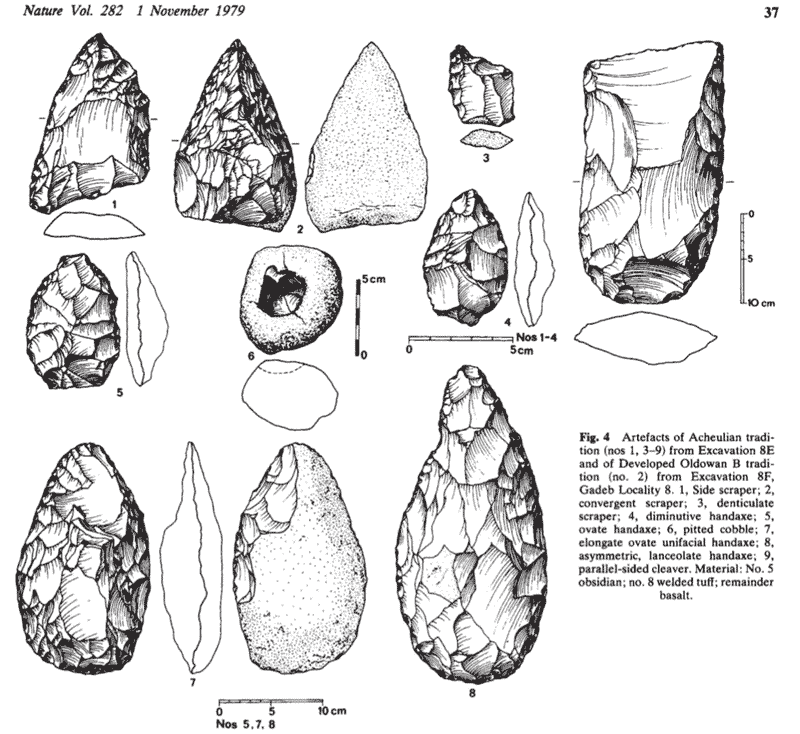

For example, the 1979 Nature article describing the Gadeb assemblages has only two illustrations of artifacts, this one representing two distinct sites:

The tool indicated by number 2 in this figure was the only artifact illustrated in the article from the “hippo butchery” site of Gadeb 8F. That’s only one out of 385 artifacts, of which 18.4%, or 71, were reported to be “shaped tools”. The hippo remains were not illustrated; de la Torre (2011:774) discussed these hippo remains (citing Kurashima 1978) noting that the “partial skeleton” consisted only of three tusks, one rib, and a left scapula.

What do I make of this?

Although many have cited the observation of long-distance obsidian transport at Gadeb, few examined the claim critically. An exception is Nick Blegen, who in 2017 described a later instance of obsidian transport at Baringo, Kenya. The Baringo study is a nice example of geoarchaeology, in which the chemical composition of rocks provides evidence of where they came from on the landscape. “The earliest long-distance obsidian transport: Evidence from the ~200 ka Middle Stone Age Sibilo School Road Site, Baringo, Kenya”.

Blegen explained that the source of the obsidian in the Gadeb handaxes had not been confirmed by chemical evidence:

Obsidian artifacts are rare at Acheulean sites in the Early and Middle Pleistocene of eastern Africa. When present, obsidian comprises a tiny proportion (<0.1%) of the overall lithic artifact composition (Ambrose, 2012). Four obsidian handaxes from Gadeb, Ethiopia are asserted to derive from as far away as 100 km (Clark, 1987; Féblot-Augustins, 1990), but these are not geochemically confirmed and many sources in this region remain to be documented (see Ambrose, 2012). Geochemically confirmed examples of Acheulean obsidian transport include Melka Kunture in the Ethiopian rift, where obsidian comes from 7 km away (Negash et al., 2006), and Kariandusi, Kilombe and Katabuya in the central Kenyan Rift (Merrick et al., 1994). None of the obsidian from these central Kenyan Rift sites demonstrates transport distance >15--30 km. The obsidian at all the Acheulean sites listed above was probably not acquired farther away than the sources of other, coarser grained, raw materials such as lavas (Merrick and Brown, 1984; Merrick et al., 1994). The only geochemically confirmed exception is a single obsidian artifact found in the excavations of the Acheulean site Isenya on the Athi-Kapiti Plain, Kenya, sourced to Kedong ~60 km away (Merrick et al., 1994). The Middle Pleistocene MSA sites of Gademotta are situated at the source of the Worja obsidian, and this seems to be the raw material used for most (>94%) of their lithic raw materials (Sahle et al., 2014).

From that point of view, Clark’s 1987 claim cannot be substantiated. Without a comprehensive attempt to find all obsidian sources, there may be a closer source of which Clark was unaware. But the unknown possibility of a closer obsidian source doesn’t falsify Clark’s claim of long-distance transport. The possibility is an alternative explanation that should be tested. Yet this points to an important way that standards of evidence have changed since the mid-1980s. Today, claims about the possible transport of stone by ancient hominins must rely upon data about the geochemistry of rocks across a broad region. Such data now often make it possible to positively identify obsidian sources. If a geoarchaeologist wants to say something negative about identification (“no closer source than 100 km”), that statement should be accompanied by some good sampling of rocks across that 100 km region to rule out a closer source.

But it’s also possible to go too far toward uncritical rejection of evidence. Some archaeologists have considered long-distance obsidian transport to be a “marker of behavioral modernity”. They have identified long-distance transport with trade, social organization, and logistical planning—all things that sound very advanced and complicated. From this point of view, if a species that wasn’t a modern human actually moved a few obsidian flakes across the Gadeb Plateau, it looks like an inconsistency. This bias makes the claim look extraordinary.

In my opinion, archaeology needs new ways to talk about rare observations. Obsidian is a rare raw material in most archaeological sites. It stands out. Archaeologists will tend to register cases where obsidian occurs in a site, and will be interested in its source.

In recent times, stone knappers have highly valued obsidian and traded for it over long distances. It is tempting to look at long-distance transport as evidence of such trading networks. But 100 km is only two or three days’ travel. Finding a rare handful of cases in the Middle Stone Age of obsidian transport over such a distance does not establish that trading networks were common. Rare behaviors do happen. They may enlighten us about the capabilities or broader behavior patterns of past people, or they may just tell us about singular events or circumstances.

It is reasonable to seek additional evidence to make claims about rare behavior in the past more reliable and replicable. Sometimes when archaeologists first notice a rare observation and start seeking out additional cases, they find them un unexpected abundance.

This was what happened after Marco Peresani and coworkers reported in 2011 on the Neanderthal harvesting of feathers from birds at Fumane Cave: “Late Neandertals and the intentional removal of feathers as evidenced from bird bone taphonomy at Fumane Cave 44 ky B.P., Italy”. Other archaeologists examined collections from Neandertal sites, some excavated more than a hundred years before, and found more and more evidence of the same behavior. Today I look at this as a beautiful example of how new discoveries prompt scientists to re-examine old evidence for signs they might have missed.

Update

In January 2023, Margherita Mussi and coworkers reported on their work at the locality of Simbiro III at Melka Kunture, Ethiopia. The site has archaeological material stratified in layers that were on the ancient floodplain of the Awash River, buried around 1.2 million years ago.

One of the layers has a dense array of worked handaxes that Mussi and collaborators interpret as the remnants of an ancient dedicated area for tool production—a “workshop”.

“Following the deposition of an accumulation of obsidian cobbles by a meandering river, hominins began to exploit these in new ways, producing large tools with sharp cutting edges. We show through statistical analysis that this was a focused activity, that very standardized handaxes were produced and that this was a stone-tool workshop.”—Mussi and coworkers

These tools were not the result of long-distance transport of obsidian. Obsidian is located nearby with sources within several kilometers, and obsidian cobbles occur within the riverbed. However, it does seem clear that this was a location where ancient hominins undertook focused activity for a purpose.

It is not surprising that obsidian would have drawn them. Its excellent qualities for flaking enabled the creation of controlled edges on well-shaped tools. As Mussi and collaborators point out, the Melka Kunture area has obsidian tools dating back much earlier and from Oldowan traditions. I don't think it is too much to speculate that sites like this with high-quality stone may have helped to sustain the tradition of handaxe manufacture.

The Melka Kunture area is south of Addis Ababa on the upper Awash River. This itself is a long distance from the Gadeb region where obsidian attracted Desmond Clark's attention. That being said, I think that these cases are related. In the Gadeb region, what got Clark's attention was the presence of handaxes from more than 100 km to the west, in the Rift Valley. That is the approximate distance and direction of Melka Kunture.

The workshop at Simbiro III could have given rise to handaxes transported as far as Gadeb. Even if they did not come from exactly this locality or time, the attention that ancient hominins gave to obsidian in the upper Awash may have driven the interactions or movements of groups across a broader span of time. These episodes need not have been directly connected for both to inform us about a broader pattern of behavior. Obsidian might be an ideal signal to us about the interests and motivations of hominins who made these early Acheulean tools.

References

Blegen, N. (2017). The earliest long-distance obsidian transport: Evidence from the ∼200 ka Middle Stone Age Sibilo School Road Site, Baringo, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution, 103, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.11.002

Clark, J. D. (1987). Transitions: Homo erectus and the Acheulian: the Ethiopian sites of Gadeb and the Middle Awash. Journal of Human Evolution, 16(7), 809–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(87)90025-X

de la Torre, I. (2011). The Early Stone Age lithic assemblages of Gadeb (Ethiopia) and the Developed Oldowan/early Acheulean in East Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 60(6), 768–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.01.009

Mussi, M., Mendez-Quintas, E., Barboni, D., Bocherens, H., Bonnefille, R., Briatico, G., Geraads, D., Melis, R. T., Panera, J., Pioli, L., Domínguez, A. S., & Jara, S. R. (2023). A surge in obsidian exploitation more than 1.2 million years ago at Simbiro III (Melka Kunture, Upper Awash, Ethiopia). Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01970-1

Peresani, M., Fiore, I., Gala, M., Romandini, M., & Tagliacozzo, A. (2011). Late Neandertals and the intentional removal of feathers as evidenced from bird bone taphonomy at Fumane Cave 44 ky B.P., Italy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(10), 3888–3893. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016212108

Williams, M. a. J., Williams, F. M., Gasse, F., Curtis, G. H., & Adamson, D. A. (1979). Plio–Pleistocene environments at Gadeb prehistoric site, Ethiopia. Nature, 282(5734), Article 5734. https://doi.org/10.1038/282029a0

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.