A look at the intentional markings of Homo erectus

Looking at a 2014 paper by Josephine Joordens and coworkers, which describes zig-zag markings on a shell from Trinil, Indonesia. This shell may have been intentionally marked by Homo erectus.

Josephine Joordens and colleagues describe the utilization of freshwater mussels by ancient humans at Trinil, Java. The Trinil fossils were recovered by Eugene Dubois beginning in 1891, from the same site that produced the famous skullcap, tooth and femur that he named Pithecanthropus erectus. This set of hominin specimens was collected from an ancient river terrace, together with thousands of fossil bones of other animals, and the shells of a number of mollusc species. Joordens and colleagues worked with that original collection of shells to understand whether the hominins, which we now call Homo erectus, could have been using these aquatic resources.

The study has two interesting findings. First, the shells show that Homo erectus was a discerning mollusc predator. The most common shell in the deposit is of a freshwater mollusc called Pseudodon vondembuschianus, and the collection of 166 individuals includes mostly large individuals from a varied range of river habitats, indicating that they were concentrated in this area by the gatherers. Out of these individual molluscs, a third show characteristic small puncture marks in the shell at just the point where a predator would need to sever the adductor muscles that hold the shell closed. It seems that the ancient humans were systematically using a shark tooth or similar pointed tool to pierce these shells, opening them and eating the mussel inside.

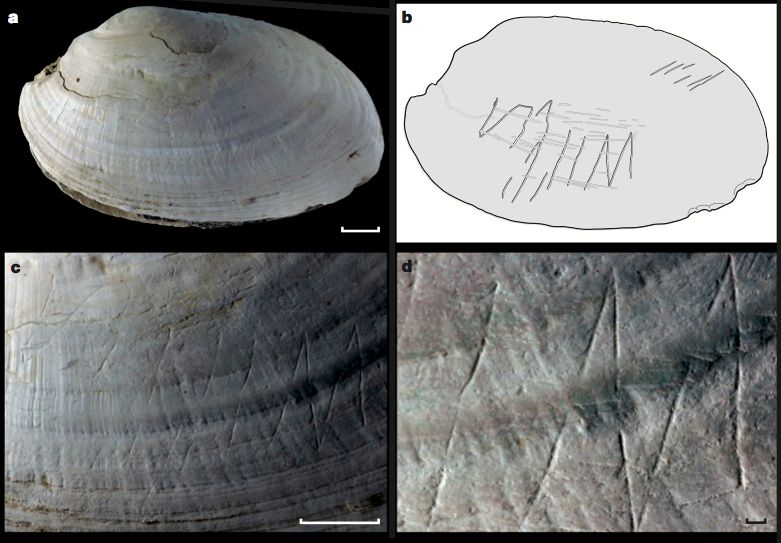

Second, Joordens and colleagues found a shell with a geometric pattern incised on its surface:

Naturally with an artifact of this nature, one may raise questions as to whether the pattern may be explained not by intentional human agency but instead by taphonomic processes or incidental markings from some functional activity. The authors considered many alternative scenarios and convincingly show that the design was created deliberately by early humans:

One of the Pseudodon shells, specimen DUB1006-f, displays a geometric pattern of grooves on centre of the left valve (Fig. 2). The pattern consists, from posterior to anterior, of a zigzag line with three sharp turns producing an ‘M’ shape, a set of more superficial parallel lines, and a zigzag with two turns producing a mirrored ‘N’ shape. Our study of the morphology of the zigzags, internal morphology of the grooves, and differential roughness of the surrounding shell area demonstrates that the grooves were deliberately engraved and predate shell burial and weathering (Extended Data Fig. 5). Comparison with experimentally made grooves on a fossil Pseudodon fragment reveals that the Trinil grooves are most similar to the experimental grooves made with a shark tooth; these experimental grooves also feature an asymmetrical cross-section with one ridge and no striations inside the groove (Extended Data Fig. 6). We conclude that the grooves in DUB1006-fL were made with a pointed hard object, such as a fossil or a fresh shark tooth, present in the Trinil palaeoenvironment. The engraving was probably made on a fresh shell specimen still retaining its brown periostracum, which would have produced a striking pattern of white lines on a dark ‘canvas’. Experimental engraving of a fresh unionid shell revealed that considerable force is needed to penetrate the periostracum and the underlying prismatic aragonite layers. If the engraving of DUB1006-f only superficially affected the aragonite layers, lines may easily have disappeared through weathering after loss of the outer organic layer. In addition, substantial manual control is required to produce straight deep lines and sharp turns as on DUB1006-fL. There are no gaps between the lines at the turning points, suggesting that attention was paid to make a consistent pattern. Together with the morphological similarity of all grooves, this indicates that a single individual made the whole pattern in a single session with the same tool.

So what can we make of this artifact? I think the most important thing to take away is that it is unlikely to be unique.

It’s a recurrent phenomenon in the study of early “art” objects that they lay unrecognized in museum collections for years after their initial excavation. The shell ornaments from Skhul, Israel and Oued Djebbana, Algeria were both found recently by Marian Vanhaeren and colleagues, despite having been excavated decades earlier. The importance of many such objects is not obvious until they are examined in comparative perspective.

The Trinil engraved shell is an example of this phenomenon. It lay in a museum for more than a hundred years, unrecognized, until the right person went to study the shells for an entirely different reason. It took looking at 166 individual mussels, most of which probably passed through the hands of ancient humans, to find one with clearly intentional markings. It is not going to be the last Homo erectus intentionally marked artifact.

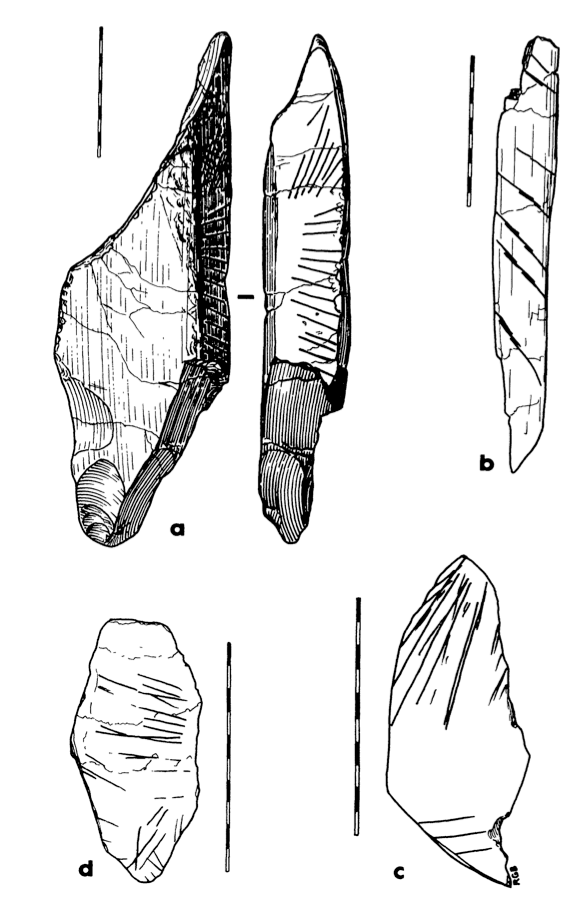

Nor is it probably the first. Robert Bednarik looked at objects with engravings or other alterations made by early humans, in a 1995 article titled, “Concept-mediated marking in the Lower Paleolithic”. The record includes many bone and ivory objects with engraved lines that are not consistent with functional activities such as defleshing or disarticulation. Along with several later sites from Neandertal times, Bednarik considered objects from Bilzingsleben, Germany, a site that preserved evidence of human activity from around 350,000 years ago. The lines engraved on bone and ivory are sometimes arranged in parallel rows, or sometimes with lines appearing to radiate from a single point. For example, here is an illustration of several of the objects from Bilzingsleben:

Who made the Bilzingsleben artifacts? The taxonomic question is boring: Who cares what species we call them? We cannot answer the cognitive question by citing taxonomy; we must examine what we know of their behavior. Pre-Neandertal European populations and Middle Pleistocene Asian populations were genetically more different from each other than living human populations are today, but the genetic evidence from Denisova suggests that those populations were interbreeding with each other at the margins – in a similar way that archaic and early modern human populations interbred within the Late Pleistocene. This is not enough to conclude that the cultural abilities of all these populations were identical, but it does suggest that they substantially overlapped in cognition and communication.

What we know about the marking behavior of later humans helps to illustrate just how much the record of behavior has decayed due to the normal taphonomic destruction of sites. Only by using more intensive and careful collection strategies are we beginning to overturn the inevitable loss of information. The discovery of ochre droplets from an early Neandertal context, more than 200,000 years ago in the Netherlands, as reported by Wil Roebroeks and colleagues (2012) is another example of something that would have been completely missed by a less careful excavation protocol. The ochre droplets are an instructive case because ochre marking is an activity that leaves no permanent archaeological trace unless it occurs deep inside caves on geologically inert surfaces. Only the discovery of ochre crayons with signs of use, such as grooves produced for pigment removal, have in the past provided some archaeological documentation of ochre marking, and even then the archaeologist may not be able to reject the hypothesis that the ochre was used for quotidian purposes like mastic instead of marking of skin or objects.

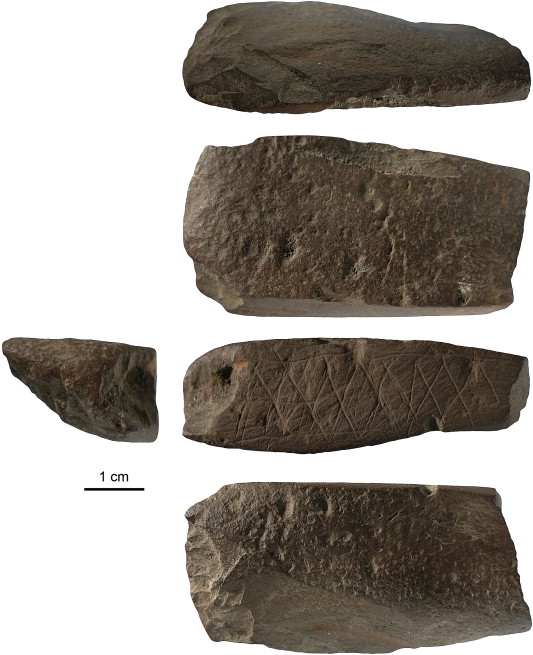

The engraved ochre pieces from Blombos are an excellent example of the variability of marked objects from Middle Stone Age and earlier contexts. The most famous piece of Blombos ochre, dating to between 75,000 and 100,000 years old, has served as an iconic artifact for illustrating the sophistication of MSA people:

The engraved side of this piece clearly has a high design content, with complementary sets of zigzag or diamond shapes and lines demarcating the ends of this row. Whatever it represents, it is clearly intentional.

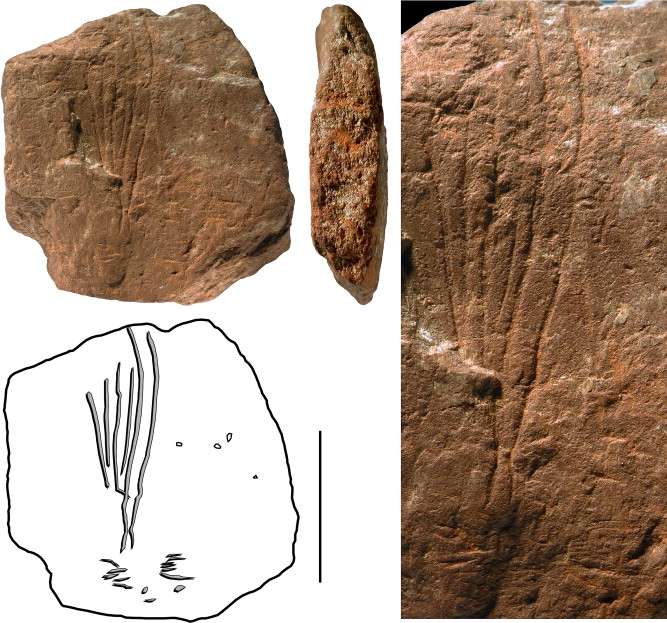

But every other engraved piece from Blombos is much more ambiguous. For example, this small piece has engraved lines that converge toward a point. Possibly they are purely a side effect of removing ochre in powder form from this small piece, or possibly the lines were intentionally placed in this arrangement. Or maybe the removal of powder was done by someone with an intentional eye for design, and never meant to last.

In fact, we can’t assume that any of these pieces were meant to communicate, or to last for any length of time. They were created by someone capable of design, but the design that they encompass may only be incidental. Bednarik discusses the regularities among the early marked artifacts in thematic or stylistic elements:

There are still other consistencies in these early marking strategies. Most seem to be reactions to aspects of the form or shape of the surface decorated in their extent, orientation, and "focus." For instance, the sets of seven convergent lines on the Stranskh skala vertebra and on the Prolom z phalanx both radiate from the object's end, as do the lines on the Prolom z tooth; the bundles of lines on Bilzingsleben objects I and 3 reflect the geometry of the support area, although not in the conceptually sophisticated way that the marks on the Tata nummulite do this. As I have noted before (e.g., Bednarik 1994a), all of the markings of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic resemble modern doodling, which is spontaneous and subconscious. Contemporary doodling, the scientific value of which remains almost entirely ignored, could well have its neuropsychological roots in our early cognitive history.

It is precisely these kinds of regularities that enable us to recognize the objects as “concept-mediated”, that is, guided by an intentional mind in some way. Even though they are not representational – at least not in an iconic, pictorial sense – the markings can be recognized as intentional. Most of these objects are much more ambiguous than the shell from Trinil. The shell marks required the maker to match the beginning and ending points of lines with each other, requiring deliberate precision.

I do not think we can dismiss doodling as meaningless. But neither do I think we should recognize it as highly meaningful. Meaning is something that archaeologists cannot reach. What we can say is that these artifacts carry information about the capabilities of their makers. The few non-perishable marked objects also speak to the likely presence of design in perishable elements of material culture. Clothing, however rudimentary, was likely to have been decorated in some way. Wooden tools were also probably notched and zigzagged – as the occasional bone and ivory implements suggest.

They lived for the first time in a world that they could change.

Reference

Bednarik, R. G. (1995). Concept-mediated marking in the Lower Palaeolithic. Current Anthropology, 605-634.

Vanhaeren, M., d’Errico, F., Stringer, C., James, S. L., Todd, J. A., & Mienis, H. K. (2006). Middle Paleolithic Shell Beads in Israel and Algeria. Science, 312(5781), 1785–1788. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128139

Henshilwood, C. S., d'Errico, F., & Watts, I. (2009). Engraved ochres from the middle stone age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 57(1), 27-47. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.01.005

Joordens, J. C. A., d’Errico, F., et al. (2014). Homo erectus at Trinil in Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature (in press). doi:10.1038/nature13962

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.