Did Homo erectus get herpes from chimpanzees?

New research suggests that herpes simplex virus 2 may have invaded ancient humans from chimpanzees sometime after 1.6 million years ago.

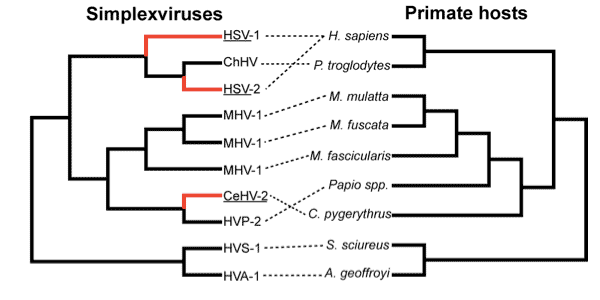

Herpes simplex viruses infect epithelial tissues of the oral and genital tracts. Humans today are infected by two different strains of herpes simplex virus, named HSV-1 and HSV-2. A new paper by Joel Wertheim and colleagues investigates the evolutionary relationship of these two strains by putting them into the phylogenetic context of herpesviruses that infect other primates. They find that the HSV-2 virus likely came from chimpanzees to infect ancient humans sometime after 1.6 million years ago.

HSV-1 is the major cause of cold sores, which are clusters of small blisters on the lips and mouth. HSV-1 can sometimes infect the genital tract, but more commonly genital herpes is caused by HSV-2. These viruses are often transmitted by people who exhibit no obvious symptoms. They can be inherited from mother to child, horizontally to sex partners, or in the case of HSV-1, just to other people who share a drinking cup. Like the chickenpox virus to which both herpesviruses are related, both will persist in nerve cells throughout an individual’s life. From here, they can cause occasional flare-ups but mostly remain hidden, and some individuals will be asymptomatic for their entire lives. Together these viruses infect between 50 and 100 percent of people in most nations of the world.

Other kinds of primates have their own herpesviruses. For many primates these are not yet known, including key species like gorillas, bonobos, and orangutans. Several different macaque herpesviruses have been sequenced, as have baboon and chimpanzee viruses along with a handful of other primates. The differences among the viruses from different primates occur in approximate proportion to the genetic differences between the primates themselves. This relation suggests that the common ancestors of these primates were also infected by herpesviruses, and that each species has inherited its virus from its ancestors.

But there are some notable exceptions. One has to do with the macaque, baboon and vervet monkey viruses. Wertheim and colleagues confirm that the herpesvirus carried by vervet monkeys is closely related to the baboon virus, even though baboons are much more closely related to macaques than to vervets.

The other exception is HSV-1 and HSV-2. Humans are the only primate known to have two different herpesviruses, and their evolution was not simple. HSV-2 is more closely similar to the chimpanzee herpesvirus, ChHV, than either of these is to HSV-1. Prior to this study, it has not been possible to resolve whether HSV-1 came into humans from a more distantly related primate, such as orangutans, whether HSV-2 came into humans later from chimpanzees, or whether both viruses may have diverged in the very distant common ancestors of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas. It even seemed possible that all ancient hominoids may have had two herpesviruses, which could have been retained in other apes but not yet discovered in them.

Wertheim and colleagues made a series of assumptions about the role of selection in pruning out ancient HSV mutations, in order to determine the timeline of divergence of the HSV-1 and HSV-2 lineages from ChHV. The resulting model suggests that the HSV-1 and ChHV viruses came from the human-chimpanzee common ancestor around 6-8 million years ago. That timeline is consistent with the hypothesis that the hominin lineage inherited HSV-1 from our common ancestors with chimpanzees – and this timeline is further supported by the fact that the resulting rate of sequence divergence is right to bring today’s macaque and baboon herpesviruses from the common ancestors of macaques and baboon species.

But HSV-2 is much more similar to ChHV, with an estimated divergence only 1.6 million years ago. With this kind of date, HSV-2 did not come from the human-chimpanzee common ancestor into ancient hominins. It instead must have come from chimpanzees or bonobos more recently.

Wertheim and colleagues suggest that the virus came into a hominin species that existed 1.6 million years ago, such as Homo erectus or Homo habilis. This is a possibility, but not the only one.

If, for example, the HSV-2 lineage came into humans from bonobos, its divergence from ChHV would still have to predate the chimpanzee-bonobo divergence, which occurred sometime before 800,000 years ago or so. So a 1.6-million-year-old divergence from ChHV would be a consistent result from a bonobo-human transmission.

Or perhaps chimpanzees have a not-yet-recognized strain of ChHV that is very divergent relative to the ChHV sequence used in this study. As in the bonobo transmission scenario, the HSV-2 strain may have come into humans very recently, even within the past 100,000 years, while still having a 1.6-million-year divergence from the known ChHV sequence.

As it stands, the ancient transmission of these viruses is an interesting problem. How did a chimpanzee virus become one of the most common sexually-transmitted diseases in humans today?

It’s not an obviously prurient question. Vervet monkeys had to get the baboon herpesvirus somehow, too. Maybe the explanation for HSV-2 is similar to that suggested for HIV from endemic SIV in West African chimpanzees – a transmission associated with human hunting and consumption of apes. If the transmission of HSV-2 really was coincident with the divergence from the chimpanzee virus 1.6 million years ago, human herpesviruses may provide some of the earliest circumstantial evidence of ancient humans hunting wild primates.

Reference

Wertheim, J. O., Smith, M. D., Smith, D. M., Scheffler, K., & Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. (2014). Evolutionary origins of human herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 31(9), 2356-2364. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu185

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.