A hard ceiling on modern human dispersal

Neandertal DNA in some of the oldest modern human genomes establishes a short timeline of 50,000 years for the out-of-Africa founder event.

One of my favorite things in science is when two different sources of information contradict each other. In such cases, a close look at both sides of the evidence often results in better understanding of nature.

Last year, two studies of Neandertal mixture into ancestral humans placed the tightest-ever constraint upon the timing of this modern human dispersal around the world. All of today's populations of Eurasia, Oceania, and the Americas emerged from an ancestral founder population that lived less than 50,000 years ago. I wrote about this work as one of last year's top 10 discoveries from DNA about ancient people.

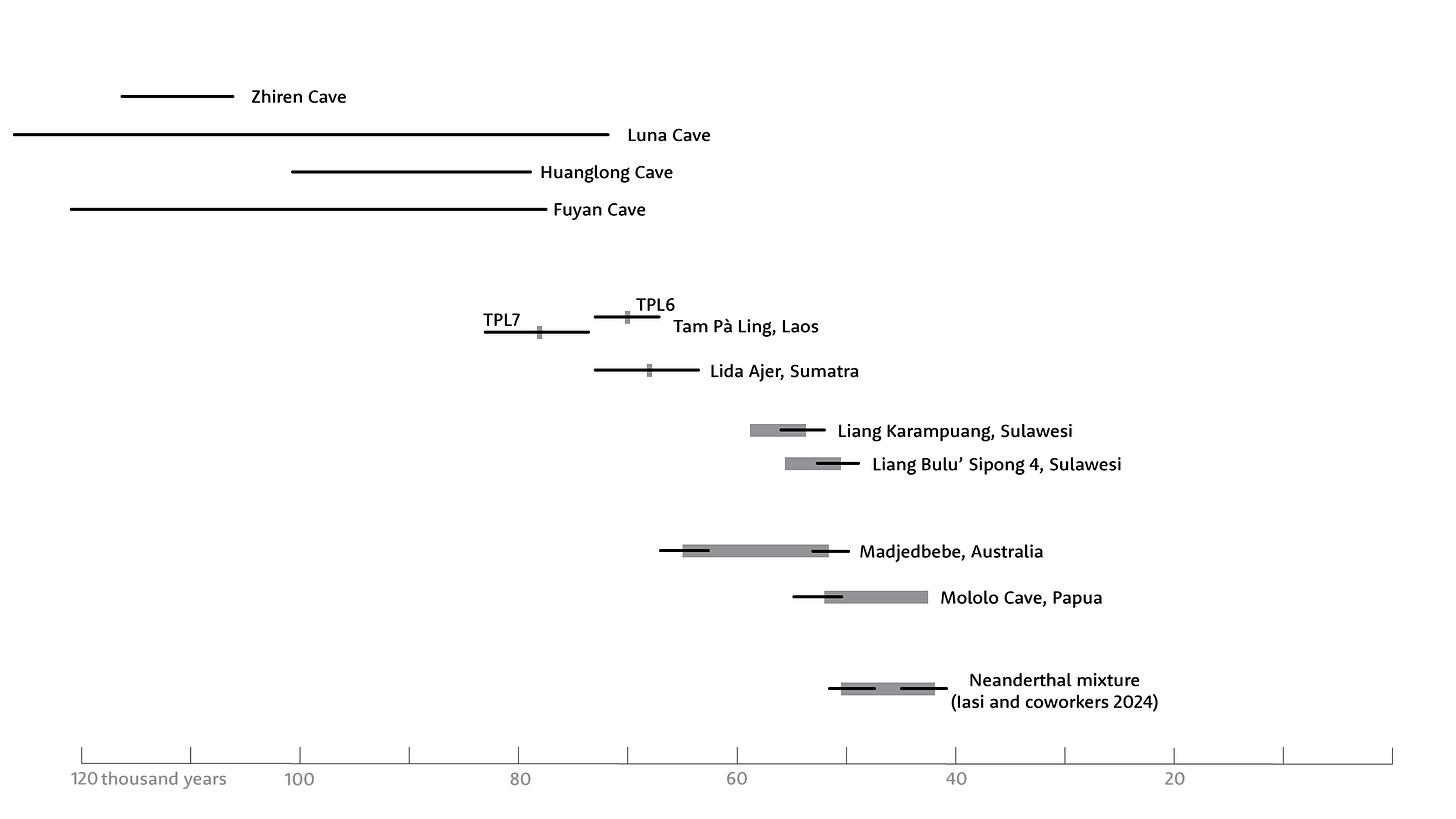

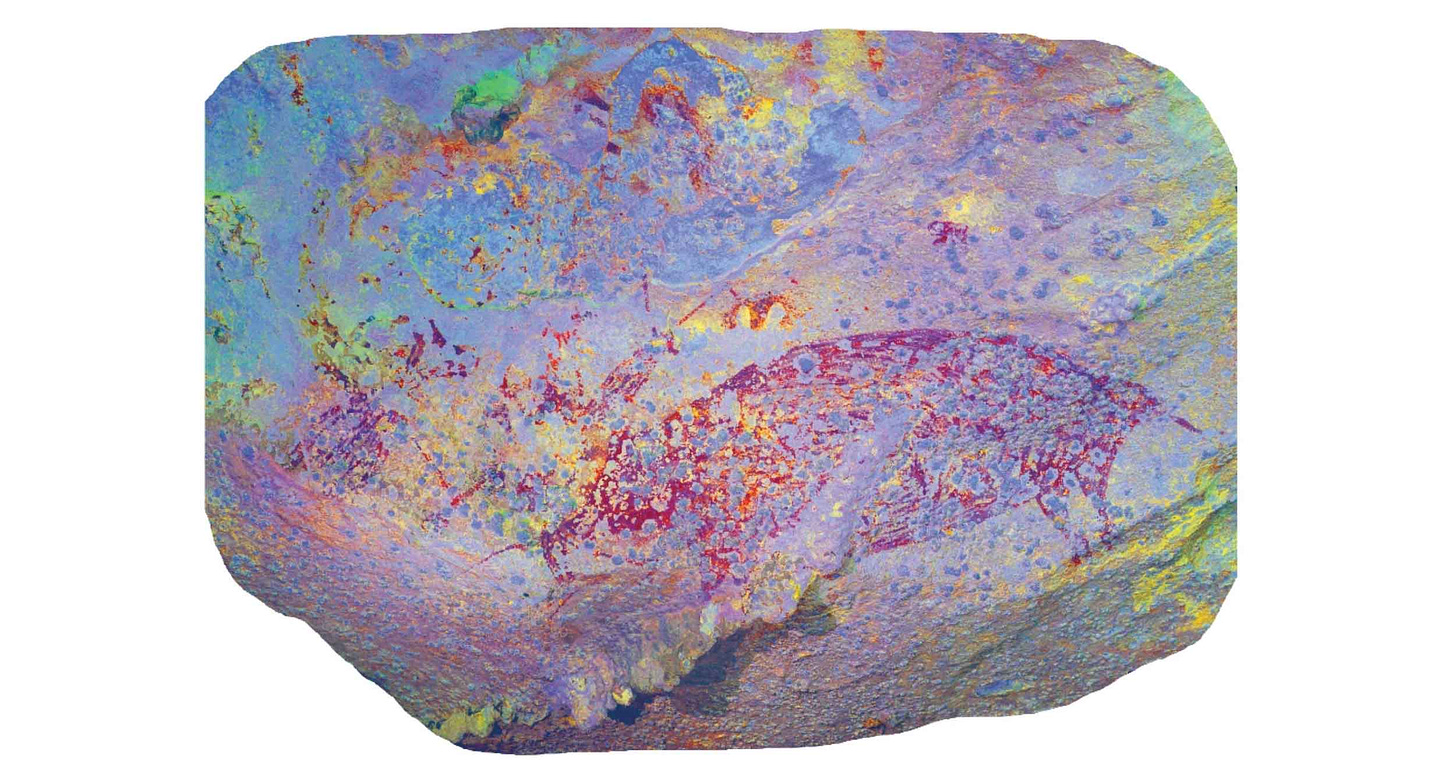

This short timeline is a clear contradiction with an array of archaeological and fossil evidence from Australia, southeast Asia, and China, all seeming to show that modern people were present much earlier. In Australia, the oldest evidence is 65,000 years; in China it may be more than 100,000 years. On Sulawesi, some of the world's oldest pictorial art has recently been dated to an estimated 53,000 years ago. If the interpretation of Neandertal DNA in today's people is correct, these archaeological and fossil findings must represent other people who were not direct ancestors of today's populations.

The evidence is contradictory. I think this points a way toward a more interesting set of interactions in the Late Pleistocene population history of eastern Eurasia.

Neandertal ancestry as a clock

A small fraction of Neandertal DNA is scattered across the genomes of today's people, broken into sequences of linked DNA known as haplotypes. Haplotypes are shared by genealogical relatives. The more distant the relative, the shorter the shared haplotypes due to the recombination of parental chromosomes. This decay of haplotypes across generations provides a way of dating population mixture.

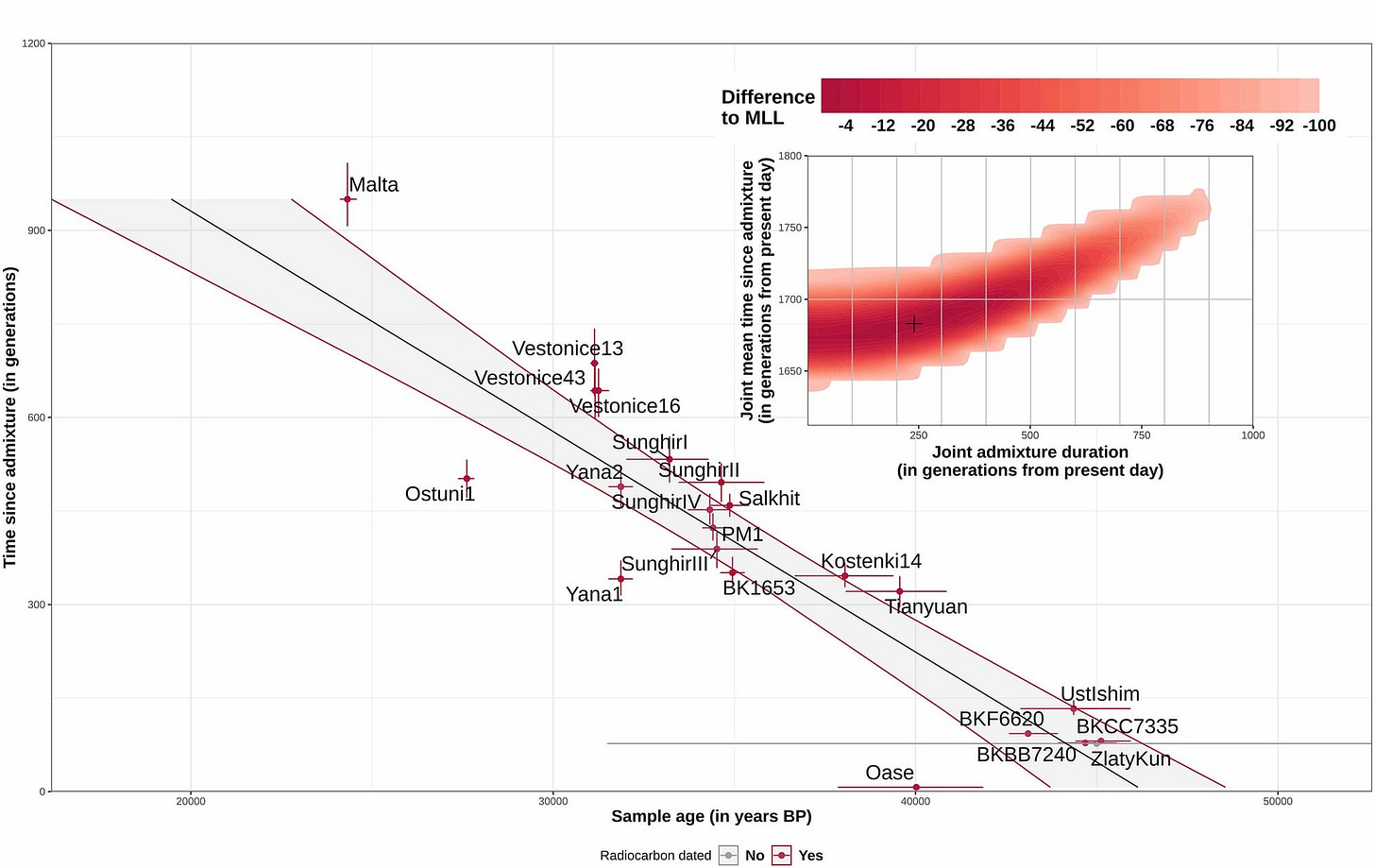

In 2012, Sriram Sankararaman and collaborators estimated when Neandertals mixed with other ancestors of modern people by summarizing the lengths of haplotypes of Neandertal ancestry DNA. They could place only a rough bracket around the interbreeding, stretching from 86,000–37,000 years ago. Within that interval, they suggested the most likely range was between 65,000 and 47,000 years.

A more precise timeline requires ancient genomes to pin down the rate that recombination has whittled Neandertal haplotypes down. A first step came in 2014 with the discovery of a 45,000-year-old femur from ‘Ust-Ishim, Russia. Qiaomei Fu and collaborators showed that this individual had the same Neandertal ancestors as most living people, who had lived only 7000 to 13,000 years earlier. That result clamped an upper limit on the founder dispersal for populations outside Africa. If they all carried DNA from Neandertals that lived after 58,000 years ago, the ancestors could only have begun to disperse after that time.

Two studies published last year fixed the date more precisely while shifting it forward. Iasi and coworkers included new data representing four individuals from Bacho Kiro, Bulgaria, and Zlatý kůň, Czechia, bringing the sample of genomes from 40,000 years or older up to six. All have long Neandertal haplotypes consistent with mixture within fewer than 150 generations before their birth. When all ancient genomes earlier than 24,000 years are added, the data are consistent with mixture in a tight window of 7000 years, centered on 47,000 years ago.

In the second study, Arev Sümer and collaborators obtained new ancient DNA data from six individuals from Ilsenhöhle in Ranis, Germany, all around 45,000 years old. Their DNA shows that these individuals were part of a population closely related to the Zlatý kůň individual. Among the interesting findings from this group of fossils, Sümer and coworkers took a very close look at the timeline of Neandertal ancestry found within these genomes. Their results aligned with those found by Iasi and coauthors: Neandertal ancestors of these individuals lived within a window between 45,000 and 49,000 years ago.

One mixture, not several

In the past I have been circumspect about how precisely DNA could estimate the dispersal timeline. Before 2010, the strongest evidence about the timeline came from mitochondrial DNA haplogroup ages. I had a lot of hesitation about mtDNA, due to uncertainty about the rate of mtDNA mutations and some evidence of selection on mtDNA haplogroups. The same basic issues were stumbling blocks for estimating the ages of Y chromosome haplogroups, which relied on STR mutation rates that were not well characterized. These two systems did favor a short timeline, less than 60,000 years, for the founder population of living non-Africans. I just didn't think the evidence was strong enough to settle the question.

I like the Neandertal DNA haplotypes better. The sheer number of segments, interspersed across the genome, provides greater weight of evidence. If they came from a single short period of mixture, they provide enough data to estimate this date very precisely. But that suggests an important challenge: What if the event wasn't really a single short period of mixture?

Suppose for instance that modern humans in Australia, southern China, and Europe emerged from a founder event as early as 70,000 years ago. If all of these separated groups met different Neandertals sometime after 50,000 years ago, they would share a similar timeline of Neandertal mixture, even though that mixture happened more than 20,000 years after their common founder event.

Some evidence has suggested that modern people mixed with Neandertals at several times and places. In 2015, Qiaomei Fu and team followed up on the ‘Ust-Ishim DNA with a partial genome from Oase 1, a 40,000-year-old mandible from Peştera cu Oase, Romania. This individual had a lot more Neandertal ancestry than anyone living now, an estimated 6.4% of his genome, and the long haplotypes showed that at least one of those ancestors had lived only five or so generations before. This individual was part of a blended population of modern humans that encountered and mixed with Neandertals.

In 2021, Mateja Hajdinjak and coauthors added genetic data from Bacho Kiro, Bulgaria. These individuals lived sometime between 46,000 and 42,500 years ago and shared substantial ancestry with the Oase 1 individual. Like Oase 1, the earliest Bacho Kiro individuals had more Neandertal ancestry than recent people, up to 3.8%. This pattern was confirmed in the 2024 study by Sümer and collaborators (which included Hajdinjak as an author). These individuals show that some of the earliest modern humans in Europe continued to mix with the Neandertals they encountered, resulting in blended populations.

Heterogeneity of Neandertal mixture persists today. Living people in eastern Asia have a slightly higher fraction of Neandertal DNA than people in Europe and southwest Asia. Some researchers (including me) suggested that this additional Neandertal ancestry in eastern Asia could have come from additional encounters with Neandertal groups, beyond those evidenced in western populations. The question is how often the Oase and Bacho Kiro histories were repeated when growing modern human populations met Neandertals. We now understand that a repeated contact scenario is exactly what happened with Denisovans. Modern people entering eastern and southeast Asia mixed with at least three very different populations with Denisova-like DNA.

Five years ago, it seemed that mixture with Neandertals might have followed a similar complicated course.

Today it doesn't look that way. Blended populations like those represented by Oase 1 and Bacho Kiro are the exceptions. All other genomes all seem to come from the same limited pool of Neandertal variation.

“[W]e found that the amount of unique Neanderthal ancestry is not significantly different between West Eurasians and East Asians, despite East Asians harboring ~20% more Neanderthal ancestry.”—Leonardo Iasi and coworkers

The data add up to show that Neandertal mixture in living people did not happen by Denisova-like mixture with multiple lineages. Instead, nearly all the Neandertal DNA that survives in today's people came from a limited time and place, tied to the founder population for later non-African groups.

The conflict with fossil and archaeological data

So the ancestors of today's populations throughout Eurasia, Oceania, the Americas, and North Africa were all one small group 50,000 years ago. That poses a conflict with a lot of fossil and archaeological data that seems to show that 50,000 years ago modern people had already dispersed throughout southwest Asia as far as China, mainland and island southeast Asia, Wallacea, and Australia.

In China archaeologists have identified several sites older than 70,000 years—one as old as 120,000 years—with fossil evidence that they have attributed to modern humans. In mainland southeast Asia, the site of Tam Pà Ling has evidence of modern human skeletal remains older than 68,000 years. The earliest evidence of human activity in Australia is 65,000 years old from Madjedbebe. Pictorial rock art on Sulawesi is more than 51,000 years old.

Human populations can grow fast. Conceivably, early people could have mixed with Neandertals, expanded their population toward southeast Asia, mixed with Denisovans, and reached Australia within 2000 years. But even at this breakneck speed, the first evidence of these people in Australia or Papua should be less than 45,000 years old. Not 65,000.

In 2018 James O'Connell and coworkers published a review of the archaeological and biological evidence of modern human arrival in southeast Asia and Sahul. The review followed the publication the previous year of evidence from Madjedbebe, Australia. Madjedbebe is the rock shelter site with an OSL chronology that places the oldest occupation at 65,000 years ago. O'Connell and coauthors questioned this long chronology, arguing strongly that the OSL determinations were affected by termite activity.

In their broader overview of data from the region, O'Connell and coworkers brought light to some contradictions in the evidence. Some sites had evidence that might not have been attributable to modern humans. One example was Callao Cave, Luzon—and in 2019 fossils from this site were recognized as the new species Homo luzonensis. Another was Zhirendong, China, where a mandible combines some morphological features often found in modern humans with others characteristic of archaic people. The fossils from some other sites, like Fuyan Cave, China, were clearly like modern humans, but O'Connell and coworkers could point to some challenges for their early geochronological placement. On the whole, the review posed a clear challenge: Could the fossil evidence really overturn the strong picture from mitochondrial DNA, Y chromosome, and other genetic data, all suggesting that modern humans arrived later than 50,000 years ago?

“A Madjedbebe archaeological age of 65 ka, if confirmed, would represent a group that did not contribute genetically to modern indigenous Australia–New Guinea populations.”—James O'Connell and coworkers

The debates over these sites have not quieted since 2018. Advocates and detractors of the early chronology of Fuyan Cave have issued opposing commentaries staking out their positions. Likewise, after a few published exchanges of views, nobody seems to have changed their minds about the chronology of Madjedbebe.

But the record of evidence of modern-like fossils or behavior before 50,000 years has grown. Excavations and geochronological work from Tam Pà Ling has deepened its record to earlier times. More and more evidence suggests that pictorial art was made before 45,000 years ago in Sulawesi, including last year's work by Adhi Oktaviana and coworkers showing that a panel from Leang Karampuang dates to earlier than 51,200 years ago.

The earlier moderns of southwest Asia

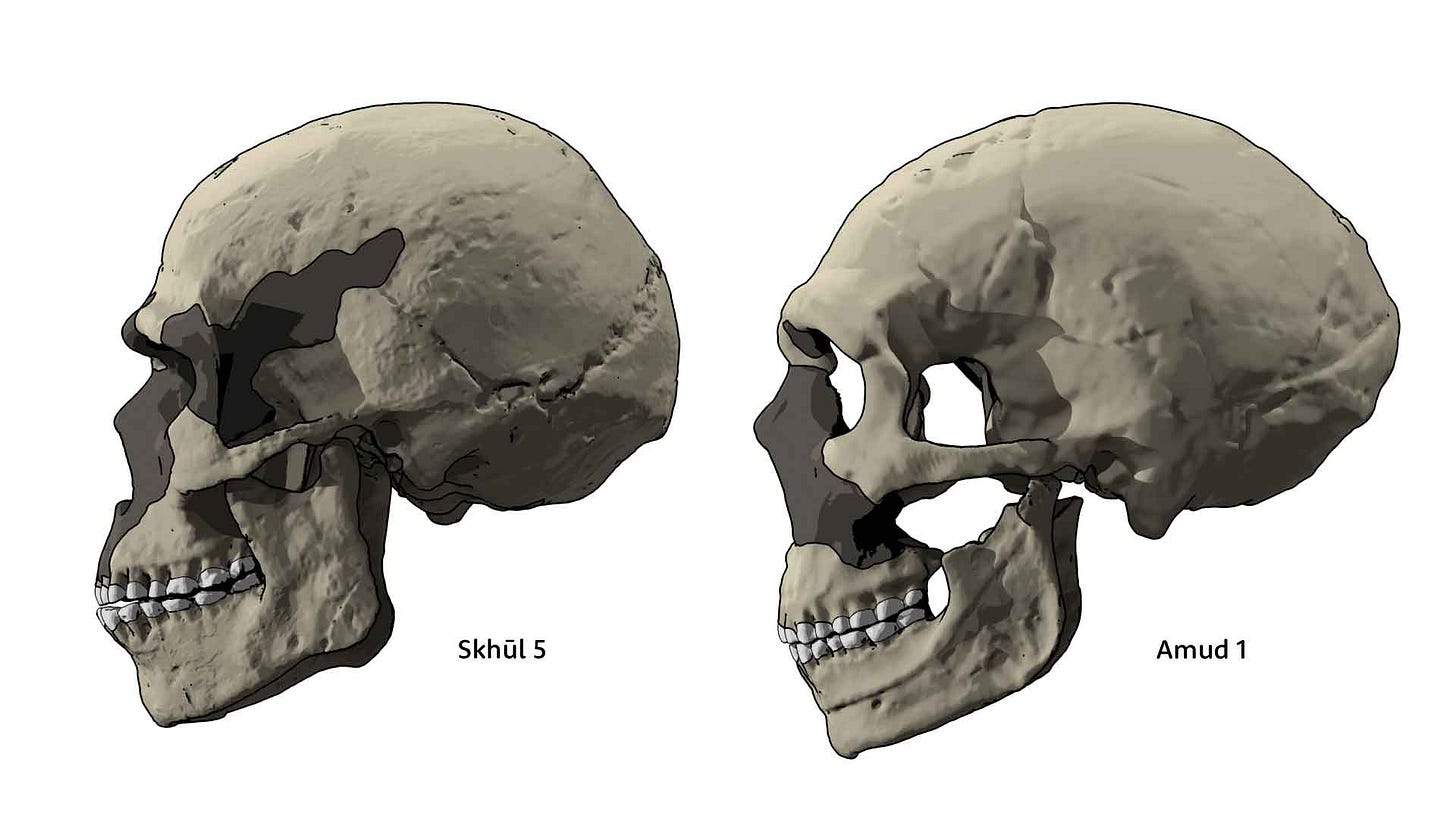

Scientists have long known that anatomical evidence of modern humans in some parts of Eurasia is older than the founder group that gave rise to today's populations. By the 1980s it became clear that fossil evidence attributed to modern humans from Skhūl and Qafzeh Caves, Israel, is earlier than 90,000 years. In more recent research, Misliya Cave, Israel, and Apidima, Greece, both have fossils arguably attributable to modern humans, both 160,000 years or older. The most common interpretation of these skeletal remains is that they come from populations whose ancestors dispersed from Africa far earlier than 50,000 years ago.

A different way of interpreting the same data is that modern-looking fossils may come from groups with local roots, which experienced gene flow from Africa resulting in similar anatomical characteristics to their African contemporaries. These are subtly different reads: the first a tree of African-derived groups, the second a network of African-influenced groups.

There is an idea that these earlier groups were not connected to the founder population that later dispersed throughout Eurasia and beyond. That idea comes from the fact that some parts of southwest Asia were inhabited by Neandertals in the period between 90,000 and 50,000 years ago. Sites like Amud, Dederiyeh, Kebara, and Shanidar all represent Neandertal-like fossils in this time interval. Archaeologists have tended to interpret this period of Neandertal occupation as the cork in a bottle, stopping modern people from dispersing beyond the threshold of Africa.

That's probably wrong. It's true that geneticists have not yet recovered DNA from modern-looking fossils such as those from Skhūl, Qafzeh, Misliya, or Apidima, taking the strongest test of their affinities off the table. However, ancient DNA evidence from Neandertals does show that gene flow entered their populations at least intermittently from sources that were more closely related to African modern humans. If they did interbreed before 100,000 years ago, and they did interbreed after 50,000 years ago, it's hard to imagine that they could not have interbred in between those dates.

A network of evolutionary change

It is in the light of this complexity within southwest Asia that I look at the growing Late Pleistocene evidence from China, southeast Asia, Wallacea, and Sahul. In the fossil record of this region between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, two things stand out: not only the growing number of modern-looking fossils, but also the lack of evidence of “archaic” fossil people. This later record contrasts with the period between 350,000 and 150,000 years, during which sites like Hualongdong, Xujiayao, Harbin, and Dali abundantly represent archaic forms of humans.

Anthropologists for the last fifteen years have fixated on whether the Middle Pleistocene fossils came from Denisova-like populations, setting up a parallel with Neandertals in the western part of Eurasia. The names Homo longi, “Julurens”, and Denisovans all have been pitched as east Asian coevals of Neandertals in western Eurasia. But these fossils in the east are not contemporaries of the vast majority of known Neandertal fossils, which come from the later period between 130,000 and 40,000 years ago.

This later time, the heyday of the Neandertals in the west, corresponds mostly to modern-looking fossils in China: Zhirendong, Luna Cave, Fuyan Cave, Huanglong Cave. Looking further toward the south, Tam Pà Ling and Lida Ajer lie in this time period. Across all of eastern and mainland southeast Asia, only the site of Xuchang has produced evidence of archaic cranial anatomy in this time period, and only at the very earliest end, before 100,000 years ago.

Two lines of evidence about the early modern habitation of east and southeast Asia contradict each other. Genetic data shows that the ancestors of today's populations dispersed into the region after 50,000 years ago. Morphology of fossils before 50,000 years ago suggests that modern configurations of anatomy were already present. I think this contradiction gives rise to a more interesting view of evolution in this region during the Late Pleistocene.

On the one hand, sites like Tam Pà Ling, Fuyan Cave, Zhirendong, and others may represent descendants of a Misliya-like ancestral group. This would be an early-dispersing population with modern morphology, pushing into the geographic range occupied by a variety of different archaic peoples. A 50,000-year timeline for the founding of today's modern populations of Eurasia don't show this idea is wrong. That timeline just shows that such early-dispersing groups ultimately had little or no direct genetic input into today's gene pool.

But I think there's a more likely possibility. Fossils from sites like Zhirendong, Fuyan, and Tam Pà Ling do share anatomical features found in modern people. But that doesn't mean their ancestry was uniquely inherited from southwest Asia. Late Pleistocene hominins in eastern Eurasia may have evolved along the same anatomical trends found in African populations, for similar reasons. One or more lineages with Denisova-like genetic heritage may have appeared modern in many aspects of their anatomy.

To be sure, gene flow from Africa and southwest Asia probably played a part in this evolutionary trend. We do not have DNA evidence from any of these Late Pleistocene groups of southeast Asia or southern China, and there is really no reason to assume they were isolated from each other or from contemporaries further to the west. If genes could flow from southwest Asia north and west into Neandertals before 100,000 years ago, certainly genes could also have flowed eastward.

In island southeast Asia, the key behavioral innovations were those that enabled dispersal between islands. While most archaeologists have assumed that modern humans were the first to cross to Sahul, there are already hints that Denisova-like populations preceded them. At least one Denisova-like population mixed with the ancestors of today's people in Papua within the last 30,000 years. The most likely place for this mixture is within Sahul itself, as modern ancestors of today's Papuan groups arrived and encountered earlier inhabitants.

The barrier to thinking about networks and connections in this part of the world has been the assumption that “behavioral modernity” is uniquely connected with “anatomical modernity”. Releasing this assumption enables us to see that there is no contradiction in finding anatomical similarities among fossil groups prior to the arrival of founders of recent populations.

There are interesting questions that emerge from this point of view. Did the environments of east and southeast Asia provide pathways of selection toward the modern anatomical configuration? What was the nature of geographic or ecological barriers that maintained high variety among earlier Denisova-like lineages? And most interesting, how did the wave of advance of founders of today's populations make headway into a region with so much anatomical and behavioral overlap?

We can address these questions with study of more recent populations, many of them abundantly evidenced by DNA and skeletal data. It will be an exciting decade for the study of human evolution in this part of the world.

Notes: The revisions to the timeline of Neandertal mixture are more or less in line with today's understanding of mtDNA and Y chromosome haplogroup ages. The complexities of mutation rate that I mention in the post are not entirely resolved.

References

Allen, J., & O’Connell, J. F. (2020). A different paradigm for the initial colonisation of Sahul. Archaeology in Oceania, 55(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/arco.5207

Bergström, A., Stringer, C., Hajdinjak, M., Scerri, E. M. L., & Skoglund, P. (2021). Origins of modern human ancestry. Nature, 590(7845), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03244-5

Clarkson, C., Jacobs, Z., Marwick, B., Fullagar, R., Wallis, L., Smith, M., Roberts, R. G., Hayes, E., Lowe, K., Carah, X., Florin, S. A., McNeil, J., Cox, D., Arnold, L. J., Hua, Q., Huntley, J., Brand, H. E. A., Manne, T., Fairbairn, A., … Pardoe, C. (2017). Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago. Nature, 547(7663), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22968

Détroit, F., Dizon, E., Falguères, C., Hameau, S., Ronquillo, W., & Sémah, F. (2004). Upper Pleistocene Homo sapiens from the Tabon cave (Palawan, The Philippines): Description and dating of new discoveries. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 3(8), 705–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2004.06.004

Freidline, S. E., Westaway, K. E., Joannes-Boyau, R., Duringer, P., Ponche, J.-L., Morley, M. W., Hernandez, V. C., McAllister-Hayward, M. S., McColl, H., Zanolli, C., Gunz, P., Bergmann, I., Sichanthongtip, P., Sihanam, D., Boualaphane, S., Luangkhoth, T., Souksavatdy, V., Dosseto, A., Boesch, Q., … Demeter, F. (2023). Early presence of Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia by 86–68 kyr at Tam Pà Ling, Northern Laos. Nature Communications, 14(1), 3193. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38715-y

Fu, Q., Mittnik, A., Johnson, P. L. F., Bos, K., Lari, M., Bollongino, R., Sun, C., Giemsch, L., Schmitz, R., Burger, J., Ronchitelli, A. M., Martini, F., Cremonesi, R. G., Svoboda, J., Bauer, P., Caramelli, D., Castellano, S., Reich, D., Pääbo, S., & Krause, J. (2013). A Revised Timescale for Human Evolution Based on Ancient Mitochondrial Genomes. Current Biology, 23(7), 553–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044

Iasi, L. N. M., Chintalapati, M., Skov, L., Mesa, A. B., Hajdinjak, M., Peter, B. M., & Moorjani, P. (2024). Neandertal ancestry through time: Insights from genomes of ancient and present-day humans (p. 2024.05.13.593955). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.13.593955

Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Mittnik, A., Renaud, G., Mallick, S., Kirsanow, K., Sudmant, P. H., Schraiber, J. G., Castellano, S., Lipson, M., Berger, B., Economou, C., Bollongino, R., Fu, Q., Bos, K. I., Nordenfelt, S., Li, H., de Filippo, C., Prüfer, K., … Krause, J. (2014). Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature, 513(7518), 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13673

Oktaviana, A. A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B., Burhan, B., Sardi, R., Adhityatama, S., Hamrullah, Sumantri, I., Tang, M., Lebe, R., Ilyas, I., Abbas, A., Jusdi, A., Mahardian, D. E., Noerwidi, S., Ririmasse, M. N. R., Mahmud, I., Duli, A., Aksa, L. M., … Aubert, M. (2024). Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature, 631(8022), 814–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07541-7

Sümer, A. P., Rougier, H., Villalba-Mouco, V., Huang, Y., Iasi, L. N. M., Essel, E., Mesa, A. B., Furtwaengler, A., Peyrégne, S., de Filippo, C., Rohrlach, A. B., Pierini, F., Mafessoni, F., Fewlass, H., Zavala, E. I., Mylopotamitaki, D., Bianco, R. A., Schmidt, A., Zorn, J., … Krause, J. (2024). Earliest modern human genomes constrain timing of Neanderthal admixture. Nature, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08420-x