Flexed burials on the right: A sign of Neanderthal-modern exchange?

New work at a site of similar age to Skhūl and Qafzeh suggests cultural sharing among groups of different biological ancestry.

Earlier in 2025, Yossi Zaidner and coworkers released a fascinating analysis of the cultural materials from Tinshemet Cave, Israel. This was the first major release of information from new excavations that began at the site in 2017.

Tinshemet is today a small cave, located in the Nahal Beit Arif around 5 km east of Ben Gurion Airport. The cave was surveyed in the 1940s by the archaeologist Moshe Stekelis, who identified Middle Paleolithic artifacts there. The cave’s small chambers are flanked by a larger terrace outside the current cave. At the time of occupation this terrace was likely covered with cave roof that has since collapsed.

In this new paper, Zaidner and collaborators report that the excavation layers both inside and outside the cave date to the period between 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. That places the site into the same 50,000-year interval as evidence of human burials represented from Qafzeh Cave and Skhūl Cave, both around 100 km to the north. Burial is a key topic of this new paper, because Zaidner and collaborators report that they have uncovered the remains of at least five ancient human individuals from the Middle Paleolithic, at least two of them apparently burials.

Back in 2020, Josie Glausiusz profiled Israel Hershkovitz, principal author on the current paper and project leader for Tinshemet. At that time, the work on preparing one of the fossil human burials from the site was well underway.

“This is probably one of the most important human fossils ever found — the earliest intentional burial that we know of. The skeleton is fully articulated and lies on its side in the fetal position, which suggests that the burial was organized. We don’t know yet if it’s a modern human, an archaic Homo or a Neanderthal, because it will take at least 18 months to expose the bones.”—Israel Hershkovitz

The article gives a great mid-Covid profile of Hershkovitz's work. Still, if there's one thing for certain in hominin evolution research, it's that no “earliest” instance of a behavior will likely hold that title for long. The significance of these burials is not that they are the “earliest”—I've helped describe some that are much earlier—but that they contribute more information to a pattern that may reflect cultural exchanges.

Burials on one side?

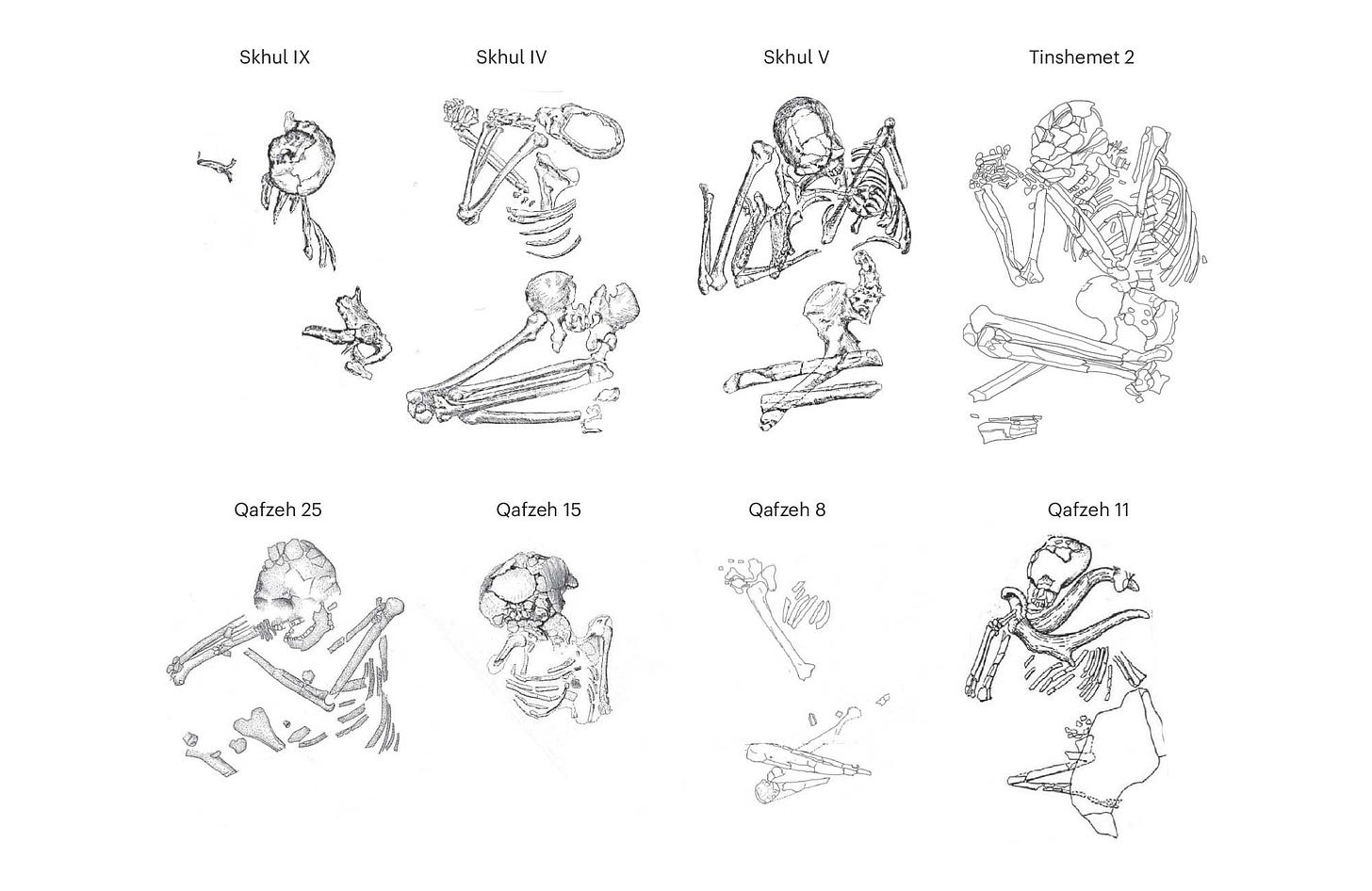

Zaidner and coworkers note an interesting coincidence among many of the burials from this 50,000-year span of time, Skhūl, Qafzeh, and Tinshemet: Bodies were buried in a flexed position, laid on their left sides. They provide an image that shows eight features from these sites that have been interpreted as cultural burials.

Is this a pattern? I have to point out that this illustration omits several burials, including the Skhūl 1 infant and the double burial of Qafzeh 9 and Qafzeh 10, both on their left sides. My feeling is, you shouldn't omit from the illustration the cases that don't fit the pattern. The task of fitting a body to a shallow hole does often lead to a flexed burial with legs to one side or the other, and putting knees to one side will tend to incline the pelvis and torso. Once we admit this shared mechanical reality, we reach the question of how much of a bias toward one side or the other is a statistical uncertainty. Eight out of eleven probably isn't.

Still, it's not the pattern of burial so much as the fact of burial that ties together many sites across this region. Several sites with skeletons interpreted as Neandertals, Amud, Kebara, and Tabun, as well as Dederiyeh in Syria, also are interpreted as burials. These sites tend to be somewhat later, mostly between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago, with the exception of Tabun where the age of the Tabun 1 skeleton may be earlier.

Shared cultural information

Back in the 1990s, the cultural evidence from sites like Skhūl, Qafzeh, Tabun, Amud, and Kebara was a centerpiece of the debate over modern human origins. Many researchers understood that if modern humans had dispersed from Africa, southwest Asia must have been their first stop. The evidence from Skhūl and Qafzeh, which in the 1980s had been attributed dates in the range of 120,000 to 90,000 years ago, were the earliest modern people in Eurasia known at that time. They were earlier than many of the Neandertal skeletal remains from other sites in the same region.

Yet these “modern” humans and the Neandertals had been found in archaeological contexts with stone artifacts that hardly differed from each other. Both kinds of skeletons seemed to occur in sites with Middle Paleolithic toolkits, with scrapers and points made from large Levallois flakes. Those were generally like tools that Neandertals made many other places. Those toolkits didn't include many clear similarities with the stone industries that would be carried by early modern humans who entered Europe. That seemed puzzling to many archaeologists, who expected that modern humans should have brought some technological advantage over the Neandertals with them from Africa.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Geoffrey Clark and John Lindly wrote a series of articles that considered this puzzle. They noted that what seemed to have been a biological transition—from Neandertals to “modern” humans and back again—had unfolded with a cultural continuity over time. For Clark and Lindly, this observation posed a strong challenge to the idea of modern human superiority. Certainly when I read their work I was impressed with the possibility that cultural and biological change seemed to follow different, somewhat distinct, trajectories.

One possible interpretation was cultural sharing among the different biological groups. That is the interpretation that Zaidner and coworkers prefer in the current paper on Tinshemet Cave. At Tinshemet, like Skhūl, Qafzeh, and other contemporary sites, the stone artifacts follow the same kinds of patterns. Zaidner and collaborators further point to the presence of more than 7000 fragments of ochre nodules in the deposit. They

“The exploitation of distant sources suggests that great efforts were invested to obtain these materials, hinting at the importance of ochre in the human activities at the site.”—Yossi Zaidner and coworkers

Who were these people?

Southwest Asia in the period between 120,000 and 60,000 years ago was a complicated human terrain. We have a lot of evidence from sites across the region that Neandertals were present at some places during this span. Evidence—mostly from different sites—also shows that one or more populations aligned with African modern humans were present at some times and places. This seems to have been a crossroads of different peoples where genetic exchanges likely happened.

Six months ago, I might have said that genetic exchanges “certainly” happened across this time in southwest Asia. However the most recent assessments of Neandertal DNA ancestry in living and ancient modern people suggest that the prime time for population mixture was between around 51,000 and 43,000 years ago. I wrote about those estimates earlier this year: “A hard ceiling on modern human dispersal”.

Tinshemet Cave, like Skhūl and Qafzeh, represents people who lived more than 30,000 years before the major dispersal of modern humans throughout Eurasia. Some archaeologists have argued that this pre-dispersal population had little or nothing to do with the founder population that would eventually spread from southwest Asia throughout the world. Zaidner and coworkers do not reveal what they think about the identity of the Tinshemet hominins. Maybe they're Neandertals, maybe modern, maybe—as Hershkovitz has suggested for Nesher Ramla—something neither clearly one nor the other.

From one point of view, the current work from Zaidner, Hershkovitz, and their collaborators have made this question less urgent. If we know these groups were sharing information and cultural knowledge with each other, then it is a mistake to think that we can predict very much about the behavior of any given group by knowing what biological ancestry they had. From my perspective, I wonder whether there is really any point in trying to define these skeletons as different groups at all.

Still, a clear demonstration of how cultural change and biological change were, or were not, related may be within reach in this part of the world. Ancient DNA must be such a high priority I cannot imagine they are not throwing every resource at it. Maybe DNA preservation is not likely. This is a part of the world where the oldest DNA preservation does not reach the age of the Tinshemet Middle Paleolithic evidence.

If it were me, I would take all the budget, and borrow against everyone’s house, to get a clear genome from such a site.

Notes: The Tinshemet Cave Project has a great website with details about the work and many photographs.

References

Clark, G. A., & Lindly, J. M. (1988). The Biocultural Transition and the Origin of Modern Humans in the Levant and Western Asia. Paléorient, 14(2), 159–167.

Clark, G. A., & Lindly, J. M. (1989). Modern Human Origins in the Levant and Western Asia: The Fossil and Archeological Evidence. American Anthropologist, 91(4), 962–985. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1989.91.4.02a00090

García, P., Zaidner, Y., Nicosia, C., & Shahack-Gross, R. (2025). Site Formation Processes at Tinshemet Cave, Israel: Micro-Stratigraphy, Fire Use, and Cementation. Geoarchaeology, 40(1), e22023. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.22023

Glausiusz, J. (2020). Picking away at fossilized skeletons. Nature, 581(7806), 112–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01319-3

Zaidner, Y., Prévost, M., Shahack-Gross, R., Weissbrod, L., Yeshurun, R., Porat, N., Guérin, G., Mercier, N., Galy, A., Pécheyran, C., Barbotin, G., Tribolo, C., Valladas, H., White, D., Timms, R., Blockley, S., Frumkin, A., Gaitero-Santos, D., Ilani, S., … Hershkovitz, I. (2025). Evidence from Tinshemet Cave in Israel suggests behavioural uniformity across Homo groups in the Levantine mid-Middle Palaeolithic circa 130,000–80,000 years ago. Nature Human Behaviour, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02110-y