The Kebara 2 hyoid speaks for itself, but is it a Neandertal?

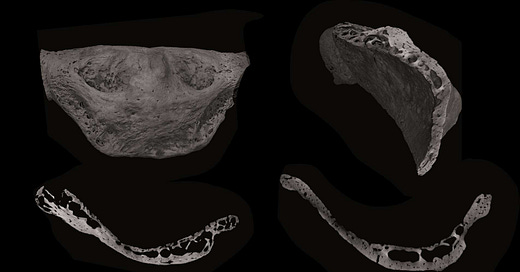

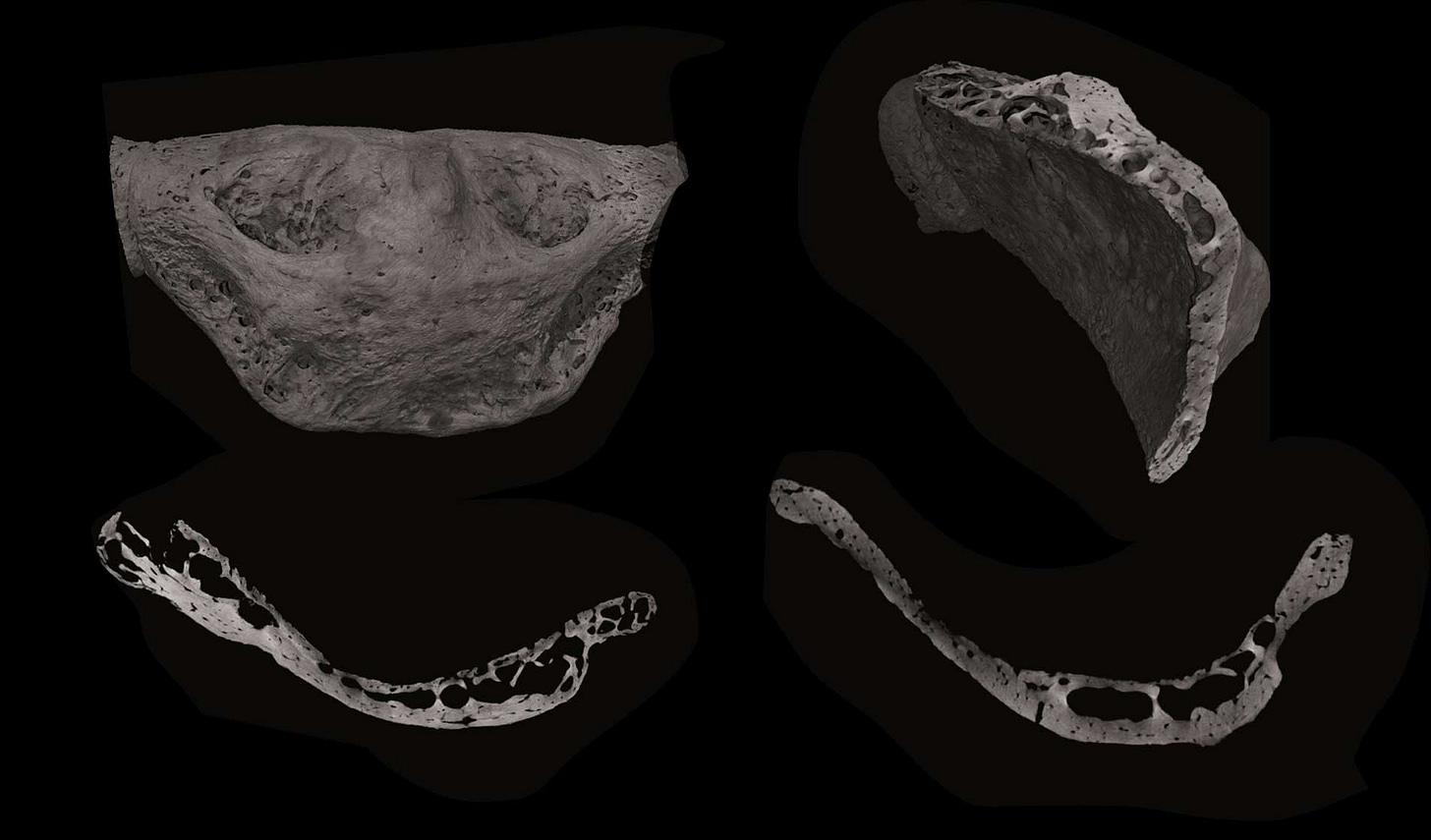

An analysis of the internal bone distribution of the Kebara 2 hyoid bone shows a pattern of forces similar to speakers of modern languages.

In an open access article in PLoS ONE, Ruggero D’Anastasio and colleagues take a closer look at the internal structure of the hyoid bone from the Kebara 2 Neandertal skeleton. The abstract is very straightforward:

The description of a Neanderthal hyoid from Kebara Cave (Israel) in 1989 fuelled scientific debate on the evolution of speech and complex language. Gross anatomy of the Kebara 2 hyoid differs little from that of modern humans. However, whether Homo neanderthalensis could use speech or complex language remains controversial. Similarity in overall shape does not necessarily demonstrate that the Kebara 2 hyoid was used in the same way as that of Homo sapiens. The mechanical performance of whole bones is partly controlled by internal trabecular geometries, regulated by bone-remodelling in response to the forces applied. Here we show that the Neanderthal and modern human hyoids also present very similar internal architectures and micro-biomechanical behaviours. Our study incorporates detailed analysis of histology, meticulous reconstruction of musculature, and computational biomechanical analysis with models incorporating internal micro-geometry. Because internal architecture reflects the loadings to which a bone is routinely subjected, our findings are consistent with a capacity for speech in the Neanderthals.

Those of us who remember the 1990s will remember the silly arguments that arose about whether the morphology of the Kebara hyoid was really humanlike, or whether anyone could even tell humanlike from apelike morphology. One specialist shamefully reported that pig hyoids resemble humans moreso than the Kebara 2 hyoid does.

Thank goodness those dark days have passed and everyone now acknowledges the behavioral sophistication of the Neandertals!

I’m far more likely to be critical of a different issue: the identification of the Kebara 2 skeleton as a Neandertal.

Sure it is robust in its upper limb morphology; it has a long pubic ramus, and it has a mandible with no distinct chin and a retromolar space. Those are all similarities with European Neandertals. But are those features enough to diagnose it as a Neandertal?

Many other specimens from Israel have been called Neandertals, such as the Tabun 1 and Amud 1 skeletons, but they don’t have the same combination of features as European Neandertals. Amud 1 in particular shares only a relative handful of characteristics with Neandertals, meanwhile it has a chin and limbs that make it taller than any other Neandertal skeleton. The Kebara skeleton is a striking specimen, but it actually presents less evidence for Neandertal affinities than these other specimens. It is missing its cranium and lower limbs, leaving mainly the mandible and thorax as evidence for Neandertal similarity.

Initially, physical anthropologists considered the Levantine samples of ancient humans to represent a mixture of Neandertal and modern traits. The interpretation of this mixture has changed over time. McCown and Keith suggested that the population was one “in the throes of evolution” from a more modern-like form to a more specialized, Neandertal-like form. Dobzhansky argued that the population was a hybrid mixture of Neandertal and modern ancestors. Later, Howell argued that the Skhul sample were possible ancestors for the early Upper Paleolithic people of Europe, “proto-Cro-Magnons”. This latter characterization is the one that has been repeated most widely, but not without dissenters.

We now know from genetics that the population we have been calling “Neandertals” across western Eurasia was much more genetically diverse than has often been assumed. At least one Neandertal population mixed into the ancestral population of present-day Eurasians and North Africans. Other apparent Neandertal populations were at least as different from each other as any of today’s Eurasian populations are from each other. We have no ancient DNA evidence at all from Israel, either from specimens widely considered “anatomically modern” or from those considered to be Neandertals.

Maybe that Levantine fossil sample represents a very different population from European or Central Asian Neandertals. Or a substantially mixed population. Or a population with North African roots that bears similarities with modern humans because of ancient gene flow within Middle Stone Age Africans. Or…

…or any number of things. I suggest that we cannot dichotomize this fossil sample into Neandertal and modern moieties. The fossils stretch for more than 40,000 years, maybe more than 60,000 years, from the Tabun skeleton, through Skhul and Qafzeh up to Kebara and Amud. The genetics now suggest that Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia saw multiple complex dispersals of people across much less time than this. Why would we assume that the crossroads of African and Eurasian peoples was like slow-motion trench warfare for 60,000 years?

The hyoid at least is clear. This skeleton belonged to an individual who used his throat in ways that involved a similar pattern of forces on the hyoid bone as those exerted by speakers of modern languages.

References:

Arensburg, B., Tillier, A. M., Vandermeersch, B., Duday, H., Schepartz, L. A., & Rak, Y. (1989). A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone. Nature, 338(6218), 758-760. https://doi.org/10.1038/338758a0

Arensburg, B., Schepartz, L. A., Tillier, A. M., Vandermeersch, B., & Rak, Y. (1990). A reappraisal of the anatomical basis for speech in Middle Palaeolithic hominids. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 83(2), 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330830202

D’Anastasio, R., Wroe, S., Tuniz, C., Mancini, L., Cesana, D. T., Dreossi, D., ... & Capasso, L. (2013). Micro-biomechanics of the Kebara 2 hyoid and its implications for speech in Neanderthals. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e82261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082261