The circumstances of the Taung discovery

The textbook story of the fossil leaves out a wider context in which scientists interpreted the first evidence of Australopithecus.

The recognition of the fossil child from Taung, South Africa, was one of the momentous events in science. One little skull was the first fossil evidence that our ancestors’ place in the Tree of Life began in Africa. The discovery helped to motivate exploration of fossil deposits across the continent, and this exploration would over time confirm the central place of Africa in human origins. This month marks the one-hundredth anniversary of publication of Raymond Dart’s description of the fossil, which gave it the name Australopithecus africanus.

Most striking to me from today’s perspective is how fast it all happened. Dart extracted the face from the rock on December 23, wrote his manuscript and sent it to London on January 6, and Nature printed it in the February 7 issue. No revisions, straight out to subscribers.

Then on February 14 Nature printed comments invited from four British experts: Arthur Keith, Grafton Elliot Smith, Arthur Smith Woodward, W. L. H. Duckworth. Wielding polite academic language like stilettos, the four sliced at the Taung story. The very name Australopithecus, wrote Smith Woodward, was “barbarous”.

What a world that was!

Often people tell the story of the Taung discovery as an academic fable. Out of nowhere, a young upstart from Australia newly transplanted to South Africa makes an unexpected discovery. The grand pooh-bahs of British anatomical science, (including Dart's own advisor!) were under the spell of the Piltdown hoax. They dismissed Dart's findings and eventually suppressed his longer manuscript describing the find.

After a decade of discouragement, Dart would ultimately be vindicated by more discoveries by Robert Broom, first at Sterkfontein and then at Kromdraai and later Swartkrans. Almost everything Dart had said about the tiny child's skull would be confirmed by dozens of fossils. By 1947 the ringleader of the pooh-bahs, Keith, admitred his error for the ages.

“I am now convinced, on the evidence submitted by Dr. Robert Broom, that Prof. Dart was right and that I was wrong; the Australopithecinæ are in or near the line which culminated in the human form.”—Arthur Keith

There is truth to this fable. Scientists can be some of the least persuadable humans on the planet. Few who make unexpected discoveries persevere through the years in the wilderness that it takes for their ideas to reach acceptance. Discoveries matter precisely because they are unexpected.

An interest in Africa

Still, the retelling of the fable over the years has disseminated some myths and misconceptions. For instance, it's a myth that scientists were not looking to Africa for discoveries like the Taung skull. Many rich finds from deep time had already come from Africa.

From his arrival in South Africa in 1897, Robert Broom began describing significant fossils from the Permian and Triassic beds of the Karoo. The British establishment celebrated his work, honoring him in 1913 with the prestigious Croonian Lecture for the Royal Society, which Broom delivered on the origin of mammals. At the opposite end of Africa, German, British, American, and French expeditions all worked in the Fayum fossil deposits of Egypt. They outlined the transition from marine Eocene to terrestrial Oligocene deposits and discovered early catarrhines including Propliopithecus—which was then interpreted as a possible common ancestor of living apes and humans.

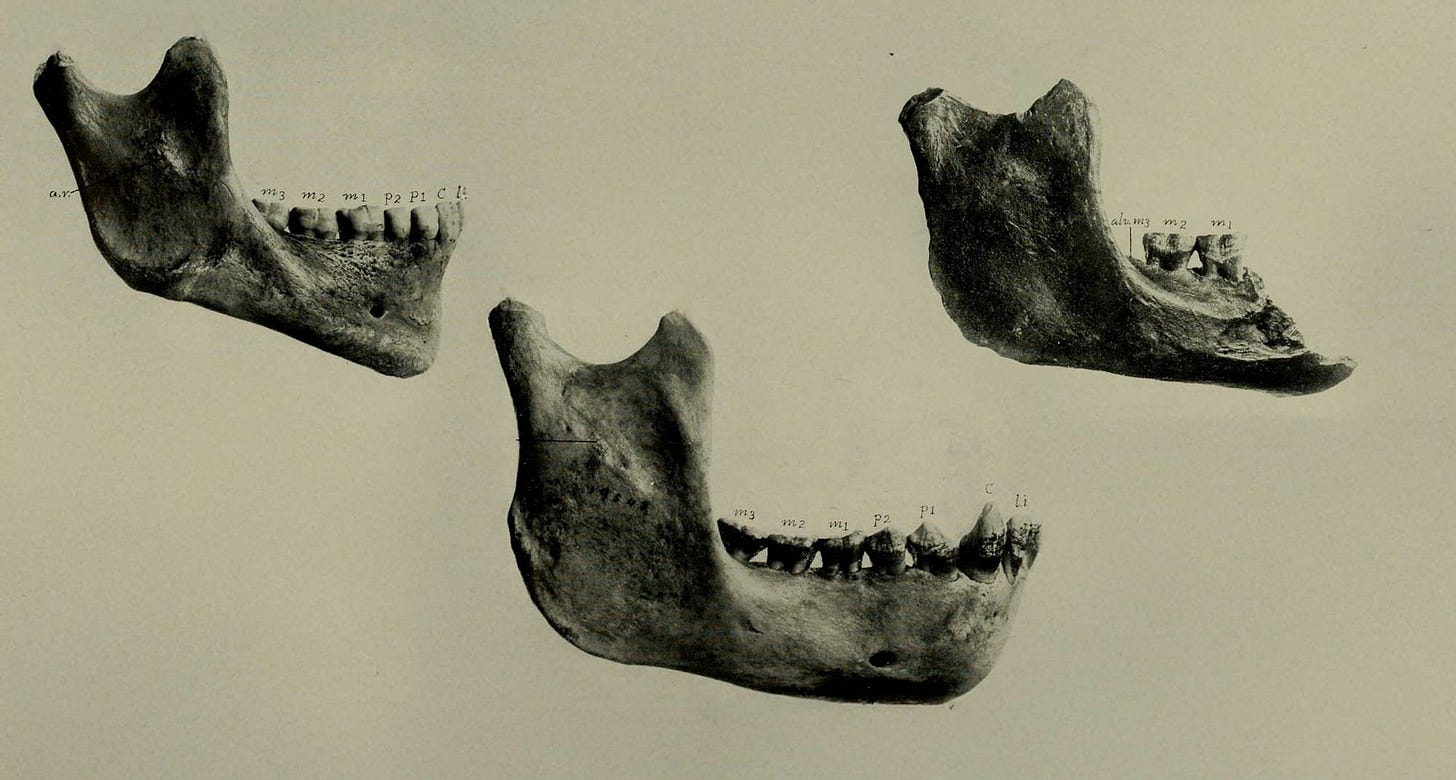

Closer to humans, in 1914 a German paleontological expedition led by Hans Reck reported on the fossil beds at Olduvai Gorge. Their finds, including an ancient human skeleton, were seen as highly significant to the deep ancestry of humankind. Later in 1921, miners in Zambia (then called Northern Rhodesia) found a skull and other bones that were sent to London, where Arthur Smith Woodward described them as Homo rhodesiensis.

Not only fossils but also the African Stone Age archaeological record was fast emerging. As in Europe, the oldest archaeological evidence recognized from Africa were large core tools from gravel pits or other river terrace deposits. In river basins across the continent, the Nile, Zambesi, Orange, and Vaal, handaxes and other artifacts revealed that the ancient artifacts found in European sites could also be found in Africa. Some archaeologists had begun to consider that Africa might be the source of ancestral tool industries.

All this was in the air when Dart arrived in Johannesburg to take up his post in January 1923. He dived in almost immediately, and Nature eagerly published the article describing his first discovery in October 1923.

That find wasn't Taung. It was something else.

Fog of racial thinking

Today we suffer enormously from hindsight when looking back at the anthropology of the 1910s and 1920s. Students learn about the handful of fossil discoveries from the period that have stood the test of a century of research. Out of the many spurious finds, most students learn only about the worst of them: the fossil fakes from Piltdown. The experts who lived in those decades had to sift through dozens more cases of mistaken identity. These were not outright fakes, but researchers misunderstood their age or identity, creating a fog of confusion.

Dart's first Nature paper was one of these.

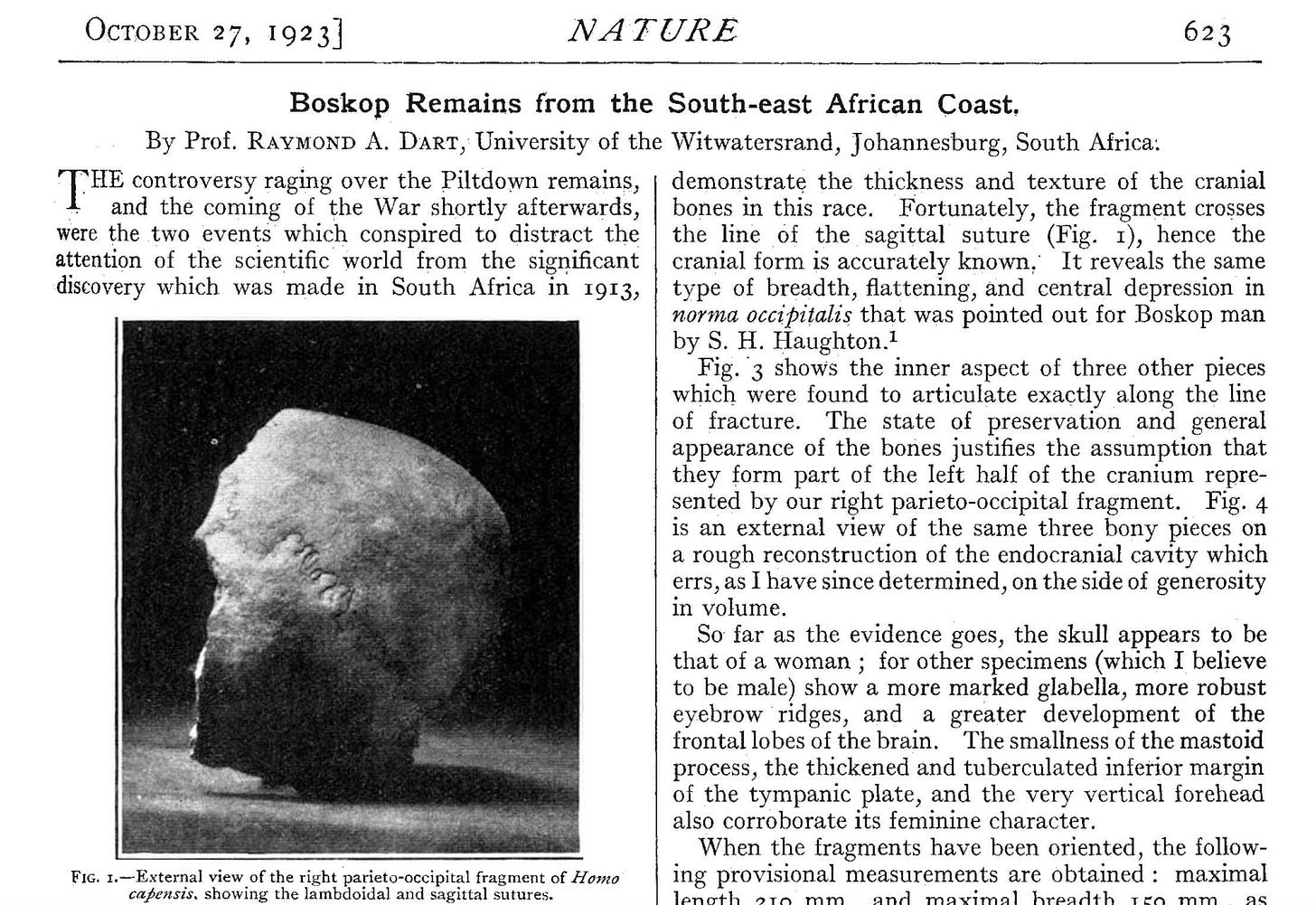

In 1923 Dart received a shipment of skeletal remains dug by F. W. FitzSimons from a rockshelter near Tsitsikamma along the southern coast of South Africa. A decade earlier, FitzSimons had involved himself with a partial skull that had been found during the excavation of a drainage ditch near Boskop, south of Bloemfontein. FitzSimons, supported by the naturalist Louis Péringuey at the South African Museum, became convinced that the Boskop fragments represented an extinct race that was a southern African equivalent of the Cro-Magnons of Europe. They described the fragmentary skull as having a massively large brain. Later, Robert Broom examined it and provided a new species name, Homo capensis. As the 1910s drew to a close, South African researchers identified several skulls from other sites as members of this purported race, the “Boskops”.

In the Tsitsikamma rockshelter, FitzSimons thought he had the proof that the Boskops race had come before the ancestors of recent Khoesan-speaking peoples of South Africa. The so-called “Boskops” skeletal pieces were from deeper parts of the deposits, under other skeletons that he considered more representative of recent groups.

Dart agreed. His Nature announcement of the find, “Boskop Remains from the South-east African Coast”, accepted the notion that a Cro-Magnon-like race had existed in southern Africa. He further suggested that the rock art of the region might reflect the prehistoric influence from this “big-brained” race.

To be clear, none of these skeletal remains were what Dart, Broom and others suggested. By the 1950s scientists accepted that the so-called “Boskops” were an illusion that came from singling out only the largest skulls from the Late Stone Age-era archaeological ancestors of recent Khoesan people. Racial thinking had made a fake race.

Later in his life, Dart would write that the problems of race formation and race mixture had been central to his interests when he took up his work in South Africa. He was far from alone. South Africa was becoming central to many scientists' notions about human races. The history of interaction and mixture of peoples from different parts of the continent, three hundred years of colonization by Europeans, and the voluntary and involuntary immigration of people from Asia all contributed to anthropologists' interest in the region. An anatomist like Dart saw an unparalleled opportunity to study racial differences and mixture.

The antiquity of modern races

Dart's interest in race was typical for the 1910s and 1920s. The two central ideas of anthropology were race and culture, and the aim of the field was to understand their interrelations.

From the 1840s onward into the 1940s, most anthropologists assumed that the living races of humans must have originated very deep in the past. This notion came from noticing that sites a few thousand years old tended to have skeletons that resembled living people from the same region. Arthur Keith's 1915 book, The Antiquity of Man, lay out the argument in clear language:

“From what we have seen in Egypt, in Europe, and in North America it is certain that a human type can persist for many thousands of years. A human type changes very slowly. Therefore, we must make a liberal allowance of time for the mere differentiation of the modern type of man into distinct racial forms…. I do not think that any period less than the whole length of the Pleistocene period, even if we estimate its duration at half a million of years, is more than sufficient to cover the time required for the differentiation and distribution of the modern races of mankind.”—Arthur Keith

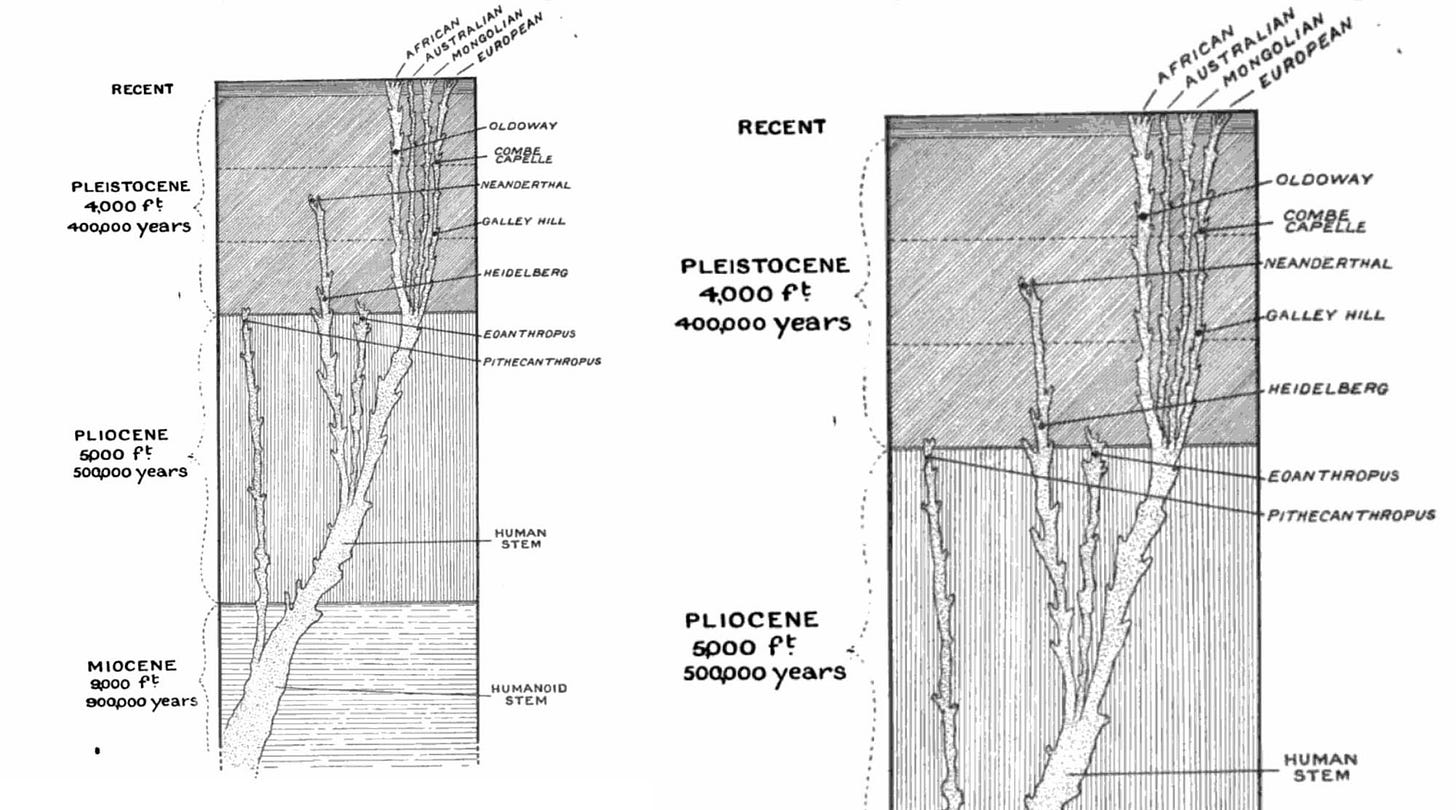

By the turn of the twentieth century, the chronology of fossil humans older than a few thousand years was giving mixed results. On the one hand were the Neandertals. By 1925 these ancient people had been found in Germany, Gibraltar, Belgium, France, and Croatia. Anthropologists accepted that Neandertals were more different from modern people than any of the living races from each other. Most were from caves or rockshelters, where archaeologists often found them with Mousterian stone tools and extinct animals.

Gravel and sand mining into the river terrace deposits in Germany, France, Belgium, and England yielded frequent discoveries of extinct animal fossils and artifacts. The succession of extinct animal species in the terraces and intervening windblown loess deposits helped reveal to geologists the chronology of Pleistocene glaciations and interglacials. Archaeologists could correlate Neandertal sites with this timeline, most of them dating to the last glacial or last interglacial.

Modern humans, too, had been found in caves from the last glacial, especially in France from sites like Cro-Magnon and Combe Capelle. These seemed to be later than most Neandertals. But from various gravel pits were skeletal remains of modern humans that researchers judged to be much older. These clouded the picture.

Today most of these supposed ancient remains are deservedly forgotten. None were truly ancient. Keith's Antiquity of Man drew attention to what he and others considered to be “pre-Mousterian” evidence of modern people: from Galley Hill, Foxhall, and Ipswich in England, from Moulin Quignon and Clichy in France, from Olmo in Italy, and others. In every case, later research would eventually establish that none of these skeletal fragments were as ancient as thought. Some were Roman-era or later.

Only one fossil from Europe known in 1925 that was much earlier than Neandertals is still accepted today. The fossil jawbone from Mauer, near Heidelberg, Germany, was found by workers in a sandpit in 1907. Today geologists think this jaw is around 600,000 years old. Otherwise, the evidence was dominated by supposedly ancient fossil evidence of modern races.

Adding to this confusion was Piltdown. Yet another gravel pit discovery, this one was faked by the collector Charles Dawson. In this find, British anatomical establishment found confirmation of some of their pet ideas about human origins: especially the idea that the main line of progress happened in the temperate and not tropical regions of the world. Nature was the epicenter of Piltdown research, the journal published more than a dozen articles and letters on the find in this period. So epochal was it for Keith that his book bore a gilded image of Piltdown on its cover.

Few researchers in other countries were so completely taken in by the hoax, although they naturally had to rely on what their British colleagues reported. In retrospect the hoax was obvious, the broken jawbone of a recent orangtuan still bearing obvious marks from Dawson's rough filing down of its teeth.

Keith's placement of the Piltdown find was more or less the consensus of those who accepted it as genuine. According to this point of view, Piltdown showed that the jaw of distant human ancestors had been apelike, while the skull already had nearly the brain size of living people. Piltdown was thought to be late Pliocene in age.

The oldest genuine hominin known at the time, Pithecanthropus erectus, preserved no evidence of jaw form at all. The brain of Pithecanthropus was substantially smaller than living people or Neandertals, and its femur showed that it stood and walked bipedally. With its small brain and apelike brow, Keith and most other anthropologists placed Pithecanthropus on a distant line. This, as its name implied, was some kind of ape-man.

A heretical fossil

Australopithecus, and the Taung skull specifically, could not fit into this model of human origins. Dart knew it. Keith knew it.

First, the Taung skull had a small brain, equivalent or smaller than a gorilla of the same dental age, just a bit bigger than a chimpanzee’s brain size. Second, its teeth were humanlike with a twist: Taung has quite large molar teeth, with a generally humanlike shape, and deciduous incisors and deciduous canine teeth that are small without any space separating the canines. These are all different from jaws and teeth of young gorillas and chimpanzees. Third, the species walked upright: The endocast and preserved face enabled Dart to estimate the size and shape of the base of the skull, in particular the position where the spine would support the skull, and this showed that the head was carried with an upright posture. Playing off the view of Pithecanthropus as an ape-man, Dart called the Taung skull a man-ape.

On the details Dart got the fossil correct, and while the reviewers would quibble on some of them, they broadly accepted the evidence.

But they and other researchers differed on their approach to classification. Today we recognize that only derived traits, newly evolved in a lineage, can support evidence of relationship. By this way of thinking, the humanlike characteristics of Taung's brain and teeth provide evidence of a relationship with humans, albeit distant, and should determine its classification. But in the early twentieth century, most biologists accepted all traits as valuable in classification, including those that were shared among the distant ancestors of an entire group of species. The four reviewers all saw the small brain and form generally like juvenile apes as guides to its classification. Perhaps it was a humanlike ape in a few ways, even a “remarkable ape”, as Keith put it, but an ape nonetheless.

Dart made the argument that we understand to be correct today: Shared traits with humans point to a common ancestry with humans, irrespective of other traits that can be found more widely among apes and other primates. This was very much a modern biological viewpoint, and it strikes me even today across Dart’s work.

At the time of first publication Dart could only speculate about the skull's geological age. One hint was that baboons had been found from the same place. Robert Broom quickly approached Dart and examined the skull. Just over two months after Dart's Taung paper appeared, Nature published Broom's comments. He had no first-hand knowledge of the Taung site, but to him the baboons pointed to a Pleistocene age.

“I think it can be safely asserted that the Taungs skull is thus not likely to be geologically of great antiquity—probably not older than Pleistocene and perhaps even as recent as the Homo rhodesiensis skull.”—Robert Broom

Reaching this conclusion, Broom added that the geological age of the specimen was irrelevant to its placement as a “missing link”. Its phylogenetic position, in other words, did not depend upon its chronological position.

Yet other scientists raised the objection that a fossil like Taung could not be an intermediate between ape and human, because it was a latecomer. As noted above, Keith and most other specialists thought that the modern races of humans already existed by the early Pleistocene. If Australopithecus lived after this time, they thought, it surely did not play a big role in human ancestry.

Bottom line

I've long admired the clarity of the Taung description and the series of letters that followed. Dart had been right about the anatomical and evolutionary placement of the skull; Broom was correct that the geological age did not detract from its phylogenetic position.

Still, having the right side of the argument did not win the day. It took more fossils to convince other researchers about Australopithecus. Broom’s work starting in 1936 at Sterkfontein brought to light more Australopithecus-like fossils. These were real, and they were old. Dart had argued based on the skull that Australopithecus was a biped, and Broom’s discoveries at Sterkfontein confirmed their bipedal status with much more of the skeleton. These South African fossils began to look to many scientists more like a stage of human ancestry.

By the time Keith recanted in 1947, the status of Australopithecus was widely accepted. Dart began a research renaissance. Students including Phillip Tobias and James Kitching renewed investigations of the Makapan valley sites, finding many fossils to add to those that Dart had examined in the late 1920s. From the breccia dumps began to come fossil Australopithecus, joining the growing sample that Broom and John Robinson were recovering from Sterkfontein.

The rest, as they say, is history. Of course, so was all that came before.

Notes: Recent books by Alan Morris and by Christa Kuljian have really good reviews of the context of discovery of archaeological and human remains in southern Africa during the early twentieth century. To coincide with the hundredth anniversary of the Taung discovery, the South African Journal of Science has published a special issue with articles about the discovery and its legacy. These articles especially emphasize some of the social and historical aspects of Dart's work and anthropology more broadly in South Africa.

Nature also has covered the one-hundredth anniversary of Taung. A news article by Elsabe Brits provides a starting point to their collection of papers and resources.

It was Wilfred Le Gros Clark who most clearly understood that the early disagreement about the Taung fossil was rooted in different approaches to classification. Clark was one of the few British researchers from the first half of the century who traveled to South Africa to examine the evidence first-hand.

References

Broom, R. (1925). Some Notes on the Taungs Skull. Nature, 115(2894), 569–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/115569a0

Clark, W. E. L. G. (1960). The Antecedents of Man: An Introduction to the Evolution of the Primates. Quadrangle Books.

Dart, R. A. (1923). Boskop Remains from the South-east African Coast. Nature, 112(2817), 623–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/112623a0

Dart, R. A. (1925). Australopithecus africanus The Man-Ape of South Africa. Nature, 115(2884), Article 2884. https://doi.org/10.1038/115195a0

Keith, S. A. (1915). The Antiquity of Man. Williams and Norgate.

Keith, Arthur, Elliot Smith, Grafton, Woodward, Arthur Smith, & Duckworth, W. L. H. (1925). The Fossil Anthropoid Ape from Taungs. Nature, 115(2885), 234–236. https://doi.org/10.1038/115234a0

Kuljian, C. (2016). Darwin’s Hunch: Science, Race and the Search for Human Origins. Jacana Media.

Morris, A. G. (2022). Bones and Bodies: How South African Scientists Studied Race. NYU Press.