Pounding water chestnuts on Jordan's ancient banks

New research highlights starch grains from many kinds of plants that were processed by pounding tools at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov.

One of the most exciting and informative Acheulean archaeological sites is Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. On a bank of the Jordan River upstream of the Sea of Galilee, the site preserves a patch of landscape upon which ancient hominins lived some 780,000 years ago. With waterlogged sediments near to the river, the site has preserved abundant evidence of plant remains—including some that were roasted or cooked by ancient people and lost within the coals of the fires they tended.

The processing of plant foods like nuts and hard starchy plant parts has been a topic of attention from Gesher Benot Ya'aqov for a long time. Naama Goren-Inbar and coworkers in a 2002 paper described the tools pitted from pounding impacts, and the array of hard seeds and nuts from the site, including pistachios, acorns, water chestnuts, and wild almonds.

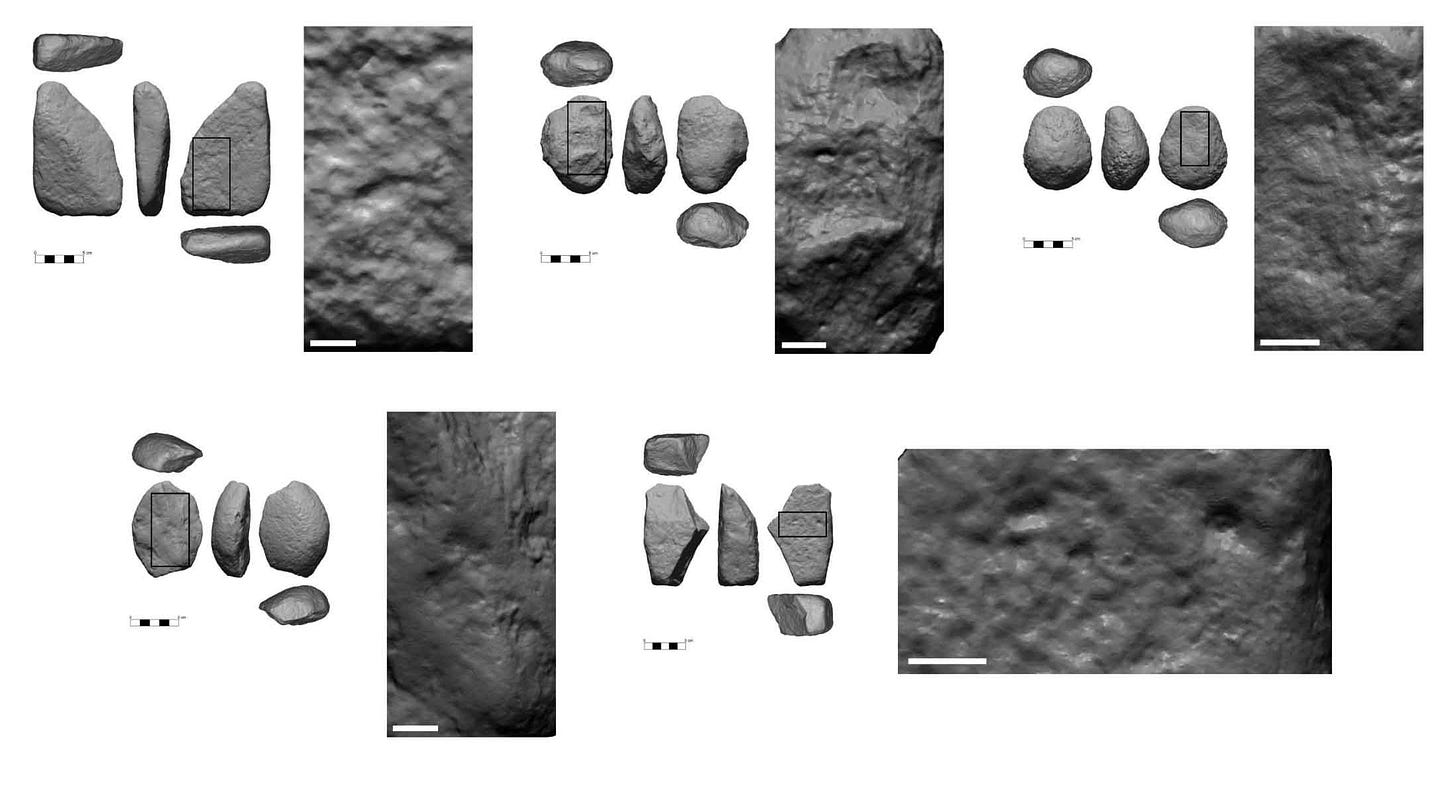

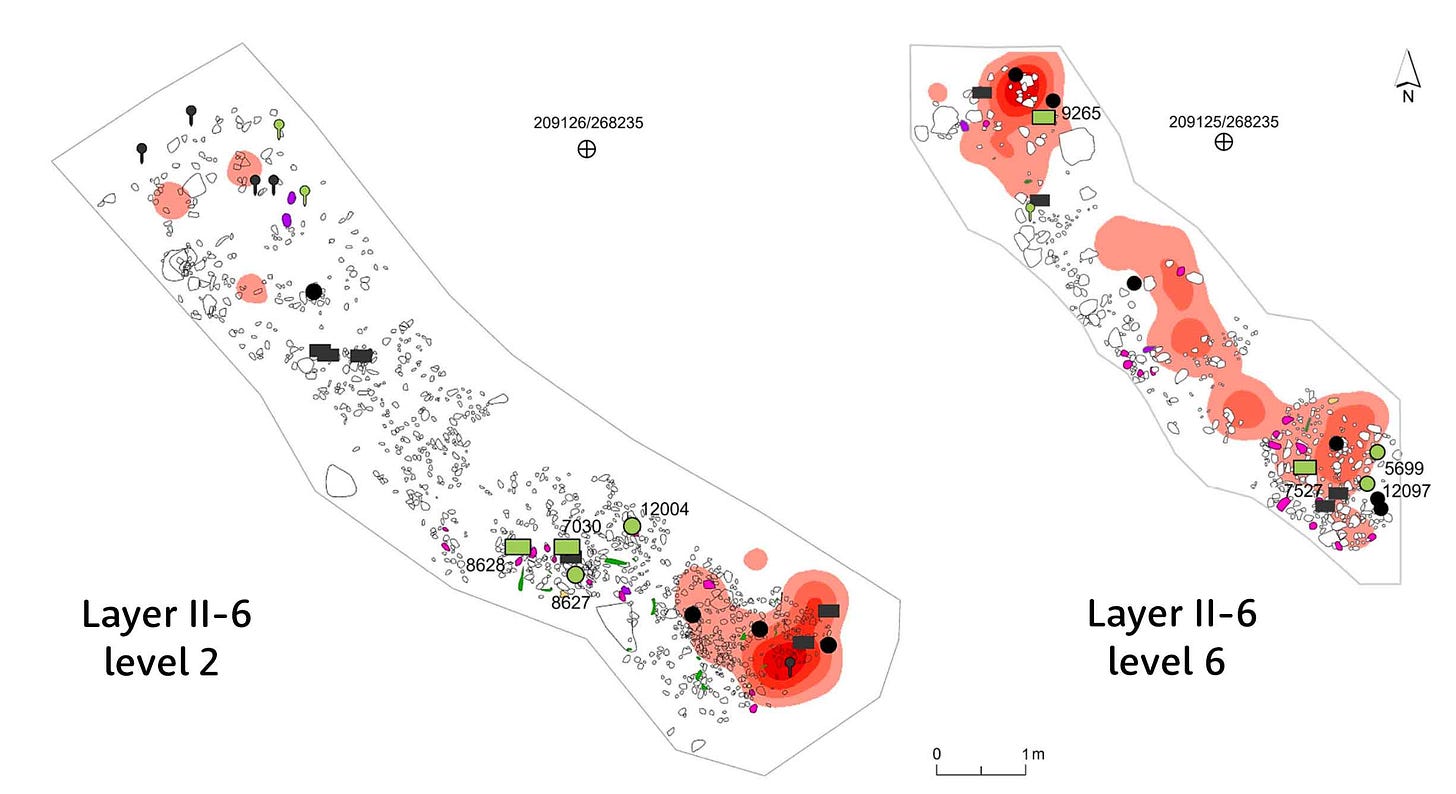

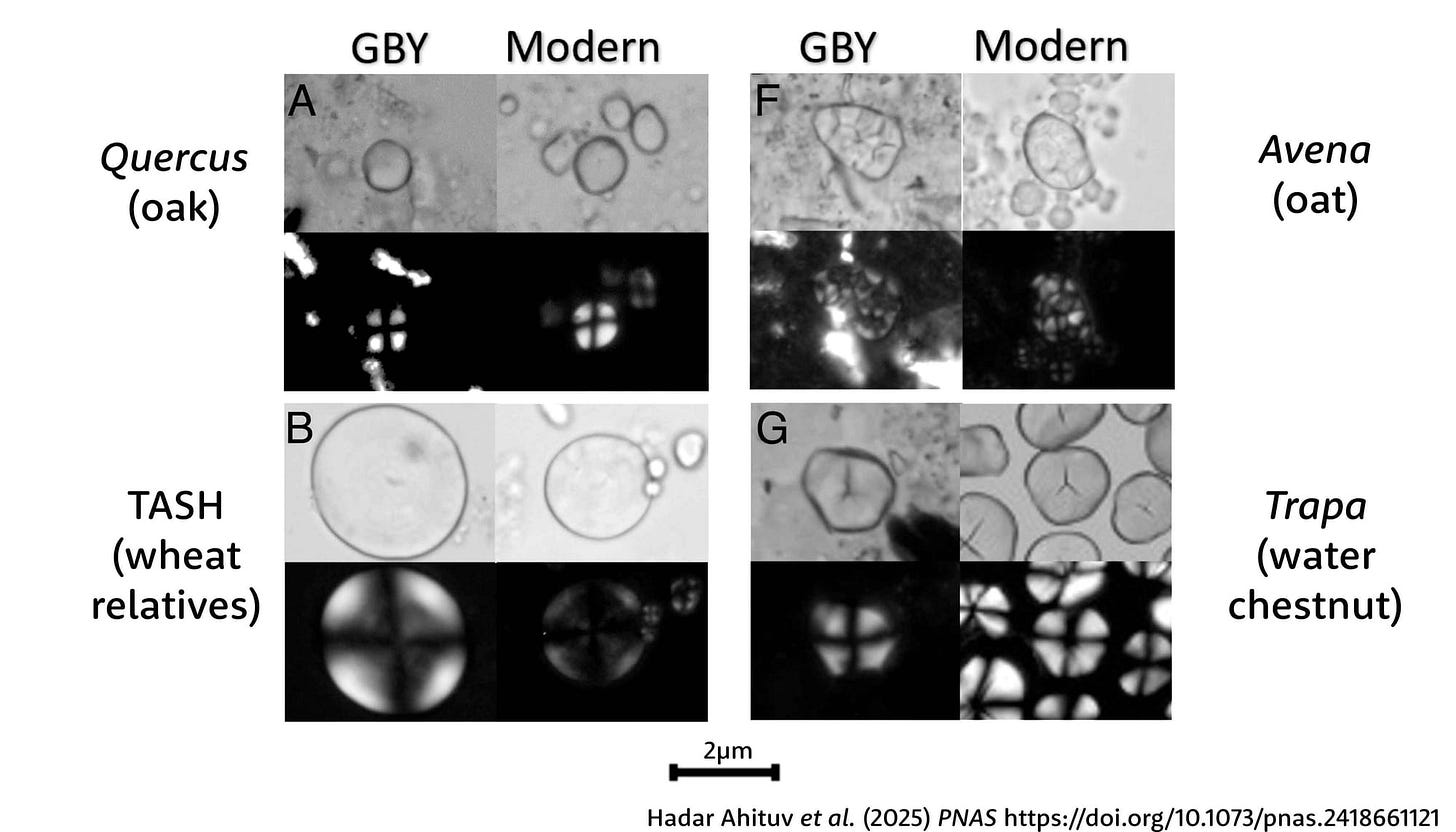

This year, Hadar Ahituv and collaborators have added a new dimension to the plant record from this important site. They did microscopic studies of the surfaces of many stone artifacts, looking for traces of plant starches that still adhere to them. Many of these artifacts were hammerstones or anvils that had been used for pounding. They discovered a fascinating mix of different plant starches on the ancient tools.

The data give a view of a remarkably varied utilization of starchy and protein-rich plant foods. On the pounding surfaces of the tools, Ahituv and coworkers found starch from acorns, lily bulbs, water lily rhizomes, oats, other grains, water chestnuts, and legumes.

In their study the researchers had to consider the possibility that starch grains might be common enough in the sediments from the site to leave traces on every artifact, even without pounding anything. To test this, they took sediment samples from various parts of the site and examined them under the microscope. They did find a few acorn starch grains in sediment samples. But the surfaces of the pounding tools had dozens of times more. Other kinds of starches were almost completely absent from the sediment samples, while hundreds of grains were on the tools. It's strong evidence that the starch grains did result from ancient food processing.

This evidence of starches expands the picture of plant use at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov. Yoel Melamed and coworkers in a 2016 paper reported on edible plant remains across many archaeological layers of the site, putting them into the broader context of edible and nonedible plants from the region. They identified tens of thousands of plant traces in the archaeological levels, and these were much more likely to include edible food plants when compared to geological layers without artifacts.

“The remains of the key food plants are 10 times more abundant in the archaeological layers than in the geological ones.”—Yoel Melamed and coworkers

The pitted stones and remains of hard plant parts like nuts and seeds, including some charred in the hearths, are very important to the picture. An additional clue about the use of plants is an intentionally-shaped wooden plank in one of the archaeological levels. The function of this wooden artifact is not known, but it may have been involved in the preparation of foods, for example as a platform for mixing mashed foods together.

Starch evidence

The study of ancient plant starches has advanced markedly in the last 15 years. Some of the most important evidence has come from samples of dental calculus from ancient hominin teeth. This approach has been widely applied to recent human groups and to ancient Neandertals. As a result, we have a much better appreciation today of the range of plant foods used by Neandertals, at least in a few parts of their ancient geographic extent. The starches in some calculus samples have signs of alterations that occur consistently in cooked starches, pointing to food preparation methods in these ancient societies.

Calculus can include other plant tissues beyond starch granules, including phytoliths, chemical residues, and small pieces of plant tissues. All of these have become important to understanding the dietary and nondietary uses of plants.

Other avenues of identifying organic remains of plants from more recent archaeological sites have been applied more and more in Pleistocene contexts. A great example is Border Cave, where many charred rhizomes and other botanical evidence were uncovered in levels dating back to 160,000 years. Starch residues on stone tools have been an important avenue of evidence also. A notable case is Ngalue in northern Mozambique, where Julio Mercader recovered starches from grass seeds on stone artifacts apparently used in grinding.

One thing I've learned by talking with people who do research on ancient starch evidence is that they don't always accept each other's results at face value. Much of this is healthy skepticism from insisting on high standards of evidence. Starch granules can be present in environmental samples that were not sites of hominin food processing. While starch grains are highly resilient, they can sometimes be damaged by burial conditions or age in ways that may be hard to tell from cooking. These kinds of alterations can lead to a challenge with equifinality: starch grains may be in a sample and present certain patterns of alterations for multiple reasons.

Questions about the work from the early 2000s has led to a growing field of study of experimental verification of starch residue analysis. Some researchers have examined the environmental presence of starches in archaeological settings, considering how to distinguish starches associated with processing by hominins from those incidentally present in soils and sediments. Work today has benefited from the growth of these experimental studies.

Starches and hominins

On the whole, studies of the trace evidence from ancient plants is helping to correct a long-standing bias in archaeology. Discussions about ancient diet once focused on the selection of prey animals by hunters and scavengers, and gave minimal consideration to where plant foods fit into ancient strategies. Those discussions were driven by a record made up largely of animal bones and teeth. Stone tools from sites were once routinely washed or scrubbed clean of sediment to better examine them. This treatment exacerbated an already-biased record, making it impossible to re-examine much of the evidence from sites excavated years ago.

The nutritional value of starch has been recognized for a long time. The archaeologist John Speth focused over many publications upon the nutritional challenges of meat as a food source. Especially during seasons of nutritional stress, humans who consume lean meat from wild animals require fat or carbohydrates to make possible the dietary utilization of protein. A 2015 review paper by Karen Hardy and coworkers describes the evolutionary importance of starches for hominins. A sign of this importance of starches to ancient hominins is the early evolution of copy number duplications of the genes for amylase, a key enzyme involved in starch digestion. The chronology of starch use suggests that a broad consumption of starchy plants was part of hominin dietary strategies from at least the beginning of the Pleistocene, and possibly much longer.

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov is a valuable signpost within this deeper history. The site's remarkable diversity of plant foods is a hint at the varied diet across the much broader hominin geographic range. The direct evidence of processing these foods, including pounding, grinding, and cooking, tells us about a system of technology that was coordinated with the foods that were selected. That full context is missing from other archaeological contexts, but sites where we have some parts of this system like Gesher Benot Ya'aqov let us understand how these components of behavior come together.

Notes: The work on amylase by Yilmaz and coworkers was included in my Top 10 stories in 2024 about ancient people from DNA.

References

Ahituv, H., Henry, A. G., Melamed, Y., Goren-Inbar, N., Bakels, C., Shumilovskikh, L., Cabanes, D., Stone, J. R., Rowe, W. F., & Alperson-Afil, N. (2025). Starch-rich plant foods 780,000 y ago: Evidence from Acheulian percussive stone tools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(3), e2418661121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2418661121

Goren-Inbar, N., Sharon, G., Melamed, Y., & Kislev, M. (2002). Nuts, nut cracking, and pitted stones at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(4), 2455–2460. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.032570499

Hardy, K., Brand-Miller, J., Brown, K. D., Thomas, M. G., & Copeland, L. (2015). The Importance of Dietary Carbohydrate in Human Evolution. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 90(3), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1086/682587

Melamed, Y., Kislev, M. E., Geffen, E., Lev-Yadun, S., & Goren-Inbar, N. (2016). The plant component of an Acheulian diet at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(51), 14674–14679. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607872113

Mercader, J. (2009). Mozambican Grass Seed Consumption During the Middle Stone Age. Science, 326(5960), 1680–1683. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1173966

Yilmaz, F., Karageorgiou, C., Kim, K., Pajic, P., Scheer, K., Human Genome Structural Consortium, Beck, C. R., Torregrossa, A.-M., Lee, C., & Gokcumen, O. (2024). Reconstruction of the human amylase locus reveals ancient duplications seeding modern-day variation. Science, 386(6724), eadn0609. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn0609