Did scientists miss a fake Neanderthal for 25 years?

An investigation claims dozens of cases of misdated bones in Rheinland-Pfalz, including the purported Ochtendung Neanderthal.

Over the last several weeks, news sources in Germany and the UK have been reporting on an apparent archaeological scandal. German authorities are investigating allegations of fraud affecting well-known archaeological finds, mostly in the Rhine valley. One is a partial skull once identified as a 160,000-year-old Neanderthal. In reality this skull may be less than one percent of that age.

The Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate) Ministry of Interior and Sports issued a press release in late November pointing to “concrete indications that archaeological finds steeped in history were deliberately manipulated by a senior employee of the GDKE (General Directorate for Cultural Heritage)”. According to the ministry, the investigation had already concluded that 21 skulls or fragments were incorrectly dated, with 18 more open cases.

Many of the sites are from Roman or Bronze Age periods in Germany. The Neanderthal case, involving a partial skull from Ochtendung, Germany, caught my direct interest. From the ministry press release:

“The case of the ‘Neandertaler of Ochtendung’ was subjected to an age determination in an external laboratory using scientific methods (Radiocarbon method/C14). This showed that the skull fragment dates to the early Middle Ages (7th or 8th centuries C.E.) and not the Paleolithic. This means a difference of 160,000 to 170,000 years younger than previously assumed.”

The press release did not name the senior employee under investigation, but a news story last week in Der Spiegel named the archaeologist Axel von Berg. According to Der Spiegel, von Berg has denied any allegations.

A lot of people who read about this story may wonder how it could be possible. Could anthropologists around the world really misidentify a recent skull as a Neanderthal for more than 25 years? I decided to write about the Ochtendung case to try to answer that question. I also hope to give some perspective on how such a revelation would matter to our understanding of the Neanderthals.

I emphasize that the facts in this case—including details about the radiocarbon assessment of the Ochtendung skull—have not been revealed to the public for examination. Without this I cannot independently assess the accuracy of the public statement from the Rheinland-Pfalz Ministry of Interior and Sports. I also emphasize that even if this skull is recent, this fact alone does not necessarily imply any wrongdoing, and I give all people named in the story the presumption of innocence.

Discovery of the skull

Von Berg brought the purported Neanderthal skull to light in 1997. Several years later he told the story of the discovery in a 2002 article for Archäologie im Deustchland, a popular magazine reporting on excavations across Germany. The article is written like a series of entries in an excavation diary:

“28. 3. 1997 (Good Friday): Very cloudy, light rain, cold. Arrived at the lava pit at around 8:25 a.m.; The excavator is again in front of the profile. Further removal of the remaining fill is expected immediately after the Easter holidays. About a third of the sediment in the hollow is currently gone. A piece of bone protrudes from the sediment directly above the excavator bucket. The fragment is exposed with a trowel and part of it is removed. An initial assessment on site suggests that it is a hominid. As there is a risk that the site will be lost due to excavation work, the existing profile is cleaned, roughly recorded and the skull pieces are removed from the profile section. The exact location is marked for a detailed recording after the holidays. With a Neanderthal in the pack, we head home at around 12.10 p.m.” (my translation)

The East Eifel volcanic field is a fascinating geological feature of the Rhine valley. A major series of volcanic events followed the eruption 215,000 years ago of the Wehrer Volcano west of the present Rhine between Bonn and Koblenz. For thousands of years following this eruption, basalt flows and smaller cinder cones emerged nearby, forming the East Eifel volcanic field. The pyroclastic deposits of scoria and volcanic ash covered soils dating to the interglacial period just before these eruptions.

A recent book chapter by Gerhard Bosinski and Nicholas Conard gives an overview of the archaeological importance of this area. Like almost every other landscape buried by volcanic activity, parts of the East Eifel volcanic field have been compared to Pompeii. Geologists have identified some remarkable instances of preservation, including imprints of plants. Although these ancient landscapes have been known for more than 150 years, no archaeological sites have yet been identified upon them.

Instead, the archaeology is up on the cinder cones themselves. After these cones formed, Neanderthals climbed them. According to Bosinski and Conard, they “lugged heavy quartz and quartzite pebbles” up to the craters for making stone flakes, and also brought finished tools made from other kinds of rock of the surrounding region. Here and there, these artifacts and other evidence of activity including remains of prey animals were deposited. These were later covered as the cinder deposits eroded and loess deposits blew in, building up sediment layers within the volcanic craters. By Roman times people began to quarry the lava flows and other volcanic deposits. Larger-scale quarrying during the twentieth century led archaeologists to notice the Middle Paleolithic sites within and around craters. Many sites around these quarries were investigated by archaeologists during the 1970s and 1980s.

One of those sites was within a quarry on the Wannenköpfe hill, outside the town of Ochtendung. There, work by Antje Justus during the 1980s had uncovered a site with stone tools and butchered horse remains from the period after the cinder cone formed and began to erode. Because of this archaeological work, the Wannenköpfe was already known as an interesting area with potentially more finds to uncover as quarrying continued. It therefore wasn’t unusual that von Berg should have been looking around the area before the Easter weekend of 1997.

Age of the specimen

Exactly where within this quarry area von Berg identified as the location of the skull find is ambiguous from the published record. In a 2017 paper, Daniel Richter and coworkers tried to improve the precision of the geological age estimate for the Neanderthal skull. That paper did not include any map or images of the context of the discovery, and the authors noted:

“The Neanderthal partial neurocranium was recovered during quarrying operation [sic], which prevented a precise documentation of the context. The find location is not consistently reported in the two publications providing more detailed account of the find circumstances, both authored by the discoverer Axel von Berg.”

Indeed, as I reviewed the early publications, I found that two different papers had marked two different locations on maps for the skull discovery. I’ve highlighted those two locations on the satellite image from Google Maps.

The descriptions agree in localizing the find near the top of a thick tephra layer and not from younger layers higher in the sequence. In their 2017 attempt to add precision to the age of the fossil, Richter and coworkers followed earlier investigators in developing estimates of geological age for the sedimentary layers, finding that the last volcanic activity on the Wannenköpfe had been around 190,000 to 180,000 years ago. The skull was younger than this age, but not much younger, based upon the idea that the skull was recovered from the top of a tephra layer and not from the sediments above.

Probably at this point, readers may be wondering why radiocarbon dating was not applied to the skull after its discovery. None of the early papers discuss this aspect but it is not hard to answer: If the skull really was from the location von Berg indicated, within layers that were in the range of 170,000 years old, there is no possibility that radiocarbon methods would provide any useful information. Archaeologists don’t destroy hominin bone without a substantial probability of an informative outcome.

But at least one destructive method was applied to the skull: amino acid racemization (AAR). In a 2004 paper, Reiner Protsch von Sieten, writing with von Berg and Stefan Flohr, reported an absolute date for the skull fragment based on sampling of isoleucine:

“A few milligrams of bone were selected for Amino-Acid-Dating from the most anterior section of the diploë of the largest of the three fragments.…The absolute age was calculated to bet- ween 160.000 to 170.000 years B. P. (Fra/Cal-A/a-21). This date is in good agreement with the absolute 40 Ar / 39 Ar dating (A-2-Dating) of the stratigraphy and is also in agreement with the geological dating of the various layers.” (Flohr et al., 2004: 6-7).

Reiner Protsch von Sieten

At this point I must digress to write a few words about Reiner Protsch. Less than a year after the publication of the 2004 paper on Ochtendung skull, the reputation of Reiner Protsch von Sieten began to unravel. He had long promoted himself as a specialist in radiocarbon dating. But by the early 2000s some colleagues in Germany started to suspect that Protsch's numbers did not add up. As Thomas Terberger and Martin Street began to pursue the question, they found many cases of misdating. Bones that Protsch had dated as some of the earliest modern people in Germany, from the Upper Paleolithic era, actually turned out to be from much later time periods.

According to the reporting of the time, what precipitated the investigation by Goethe University Frankfurt was that Protsch allegedly tried to sell part of the university's collection of chimpanzee skeletal material.

A good English-language account can be found in the Guardian by Luke Harding in 2005:

“‘It's deeply embarrassing. Of course the university feels very bad about this,’ Professor Ulrich Brandt, who led the investigation into Prof Protsch's activities, said yesterday. ‘Prof Protsch refused to meet us. But we had 10 sittings with 12 witnesses.

“‘Their stories about him were increasingly bizarre. After a while it was hard to take it seriously. You had to laugh. It was just unbelievable. At the end of the day what he did was incredible.’

“During their investigation, the university discovered that Prof Protsch, 65, a flamboyant figure with a fondness for gold watches, Porsches and Cuban cigars, was unable to work his own carbon-dating machine.”

The December 7 article in Der Spiegel about the Rheinland-Pfalz government investigation discusses the connection between von Berg and Protsch. According to the article, for a second doctorate, von Berg worked with Protsch as his supervisor, and this relationship ended upon the 2005 investigation that ended Protsch’s career. Readers who want to know more about that history should read the article, which includes some quotes from Stefan Flohr with his view of the situation.

Morphology

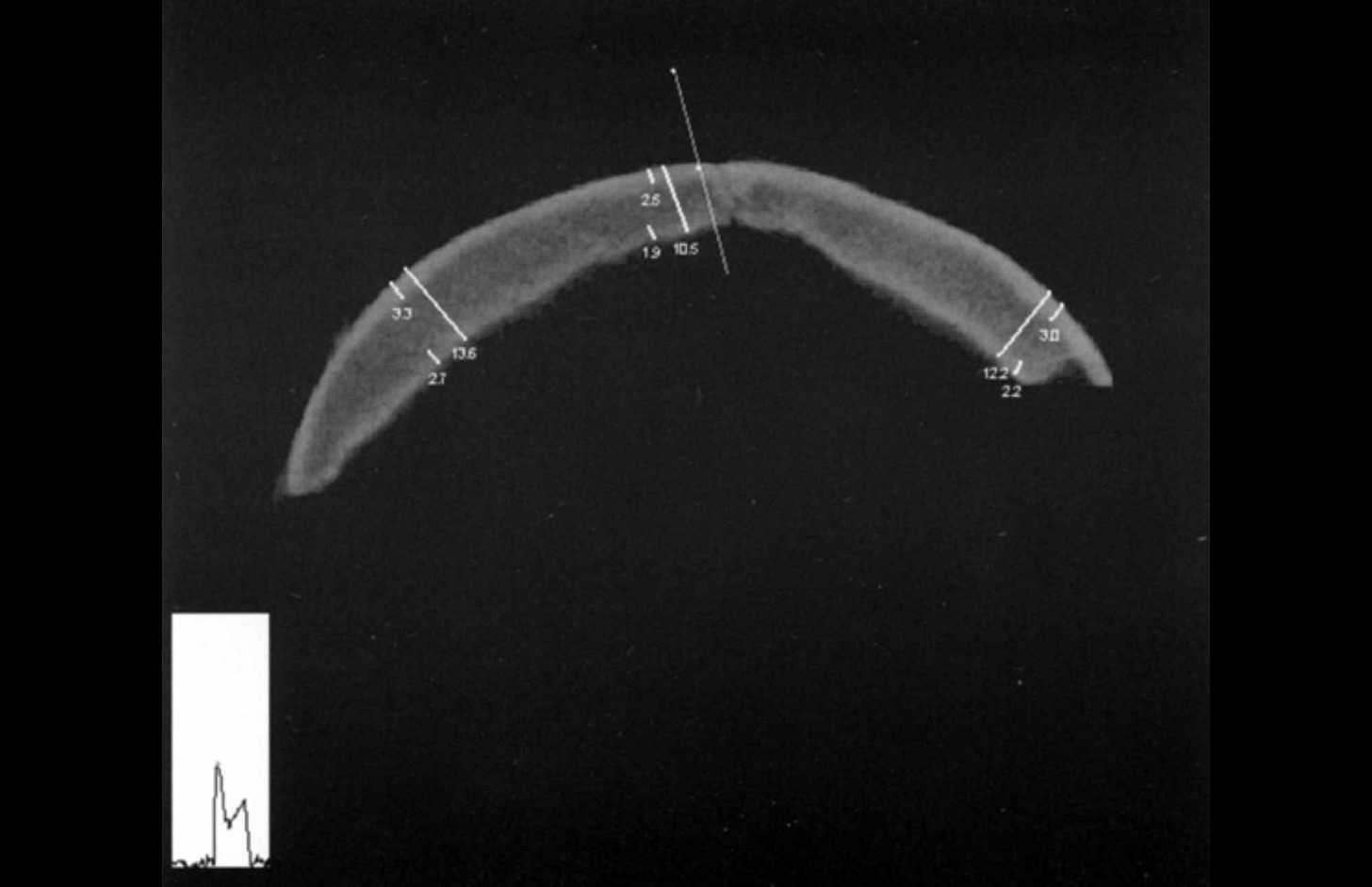

The preserved portion of Ochtendung skull includes parts of both parietal bones and part of the frontal bone. There’s not much anatomical information in this part of the skull to distinguish different human populations from each other, ancient or recent.

Two anatomical studies of the skull were undertaken during the decade following its discovery. Having so little to work with, both analyses started from the assumption that the most interesting aspect of the skull was its age. It was older than most of the fossils then identified as Neanderthals, falling into a range with fossils sometimes called “pre-Neanderthals” or “early Neanderthals”. Whether the skull might actually be modern was simply not a question that the researchers considered. Instead, they closely examined the question of whether the skull was a Neanderthal or something earlier.

Silvana Condemi, who described the remains in a 1997 museum publication and then in a paper with von Berg and Manfred Frechen in 2000, emphasized that the preserved part of the skull had relatively little curvature and that the bones were quite thick. Condemi assessed both these qualities as unusual for recent human skulls, and the low curvature suggested to Condemi that the overall skull shape had been more similar to Neanderthals. Von Berg, Condemi, and Frechen’s 2000 paper concluded that the Ochtendung skull “represent[s] an early phase in the evolution of the Neanderthals, which is defined as ‘late pre-Neanderthals’.” In other words, the fossil fit its age.

The other analysis of the morphology was by Stefan Flohr, who was lead author of the 2004 paper with von Berg and Protsch. Like Condemi, Flohr also focused on the relatively low curvature of the preserved skull portion, using a Microscribe device to plot profiles. He compared this in profile to several Neanderthals and one earlier skull from Petralona, Greece. The paper also compared thickness data between Ochtendung and skulls of Homo erectus and other Neanderthals. The study found significant overlaps among these fossil samples in the area corresponding to the Ochtendung skull, and concluded: “It is possible to assign the individual anywhere between Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis.”

Again in this case, the study was limited to the examination of fossil samples. The variation of living or archaeologically recent people was simply not included within the comparative sample. The bottom line on the morphology of this fragment is that not enough is preserved to test whether the fossil was part of a Neanderthal skull. Only the skull’s geological context made it potentially informative, and even then it could fit into any fossil group.

There was one other twist in the study by Flohr, Protsch, and von Berg: the identification of possible marks on the broken edges of the skull fragment:

“Contrary to this it is much easier to identify some tracks at the borderline of the calotte as artificial. It is thus also possible to assume that the calotte was reworked in order to use it as a tool. Another indication for the correctness of this observation is the rounded edges in the lateral area. We can thus be sure that the anterior edge of the fragment shows evidence and traces of usage and that it was probably used as a punching or even as a striking tool.”

That paragraph echoes von Berg’s description of the skull in his brief 2002 article describing the discovery, in which he likewise suggested that the skull fragment was used as a tool or worked in some way. Later in 2006, Martin Street, Thomas Terberger, and Jörg Orscheidt published “A critical review of the German Paleolithic hominin record”. This paper was an attempt to clear the radiocarbon fog that had been left by Protsch, but their discussion of the Ochtendung skull did not pick up any sign that it might be misplaced in time. But they did extend a critical eye toward von Berg’s suggestion that the skull was deliberately altered, noting that there were other processes that might abrade the edges of a skull fragment.

From today’s perspective, the idea that the edges of the skull fragments might have tool marks is intriguing. If the skull did indeed originate somewhere other than the Wannenköpfe hill, tool marks might give some hint about how a skull from another context was modified to make it look like it could really be 160,000 years old and not a medieval modern human.

Bottom line

To end the story, I return to the question I started with. How could anthropologists identify this skull as Neanderthal for twenty-five years or more? This answer is obvious: Aside from the skull’s apparent discovery context there is hardly anything to go on. The morphology of the preserved portion, on its own, does not diagnose this skull fragment as a Neanderthal, modern human, Homo erectus, or other human group.

Without much evidence from morphology, researchers who examined the skull leaned on what they understood to be its context. With any skull around 170,000 years old from central Europe, the key questions revolve around the origin of the Neanderthal lineage, the connections of Neanderthals with earlier groups—then identified either as Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis—and the relation of these groups to the archaeological evidence. Those questions determined a certain pathway of analysis and guided the choice of other fossils that the researchers included in their work.

Sadly this pathway of analysis is not very different from those applied to many discoveries. Researchers tend to focus very closely on the particular fossil samples that they think will address the questions they are examining. They tend to exclude or ignore fossils from further afield, even well-preserved ones, that they view as less relevant to their specific question.

That's a mistake. In a field with so few informative fossils for some places and times, it is crucial for anthropologists to include all comparisons, not just the ones they think are important.

It has been even more rare for anthropologists to include large samples of recent humans in their studies of prehistoric hominins. Today's human variation provides the closest biological analogue to variation in ancient hominins, but specialists too rarely examine large datasets of modern human variation. By omitting modern variation, researchers can end up producing typological work that emphasizes differences between a fossil and a typical human, instead of where the fossil may sit within the entire range of human variability. The kind of answers produced by the typological approach are the kind that you see in the Ochtendung Neanderthal case.

How would it affect scientific interpretations of this period of time in Europe, if this skull turns out not to be a 170,000-year-old Neanderthal? To be honest, if all we have to go on is the shape of the fossil, this skull fragment never had much to say.

Still, we live in an era of ancient DNA sampling. Some fossil fragments of this age have great potential to tell us about population history of early Neanderthals, if DNA is preserved. The Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in southwestern Germany has produced a Neanderthal femur, around 120,000 years old, that DNA data suggests is the most divergent lineage of western Neanderthals. The two skulls from Apidima, Greece, one looking very much like a Neanderthal and the other with a posterior cranium similar to modern humans, with a minimum age around 160,000 years ago fall right into this period. Neither has produced DNA, but together they feed the growing understanding that Neanderthal populations were connected across western Eurasia, and had recurrent networks of interactions with Africa. Any 170,000-year-old Neanderthal from this region has the potential to be extremely interesting in a world with molecular evidence.

People may ask, is there a lesson in this case for the publication process? None of the published research on the Ochtendung skull fragment was outside the norm of paleoanthropology in the 1990s and early 2000s. Most of the research was peer-reviewed in respected field-specific venues. Today for some parts of this research, it would be more routine to report more information: The amino acid dating procedure is an example where more supporting data would ordinarily be presented. But much of the content of these studies might be published today in basically the same form.

The future of research must be more open. Confidence in research comes from the ability to replicate results and trace a discovery to its source. Better research has more inclusive comparisons. Better research distributes more data to more people. It's remarkable how little information about the Ochtendung fragment has been disseminated in 27 years, that few photographs and no 3D data are readily available, and that comparisons of the specimen with skulls of recent humans are not easy to carry out by any student in the field.

Notes: Translations of German language passages into English within this post are mine, with help from Google Translate.

It's always tricky to write about ongoing investigations, particularly when all the facts have not been released to the public. The people who are subjects of the investigation have the presumption of innocence. In this post I have relied upon published information to help people understand how scientists can examine cases where the geological age or archaeological context of a fossil human may be in question.

The amino acid racemization method had a period of popularity as one of several methods capable of pushing beyond the limits of carbon-14, but challenges became clear in the 1990s and early 2000s that tempered the application of the method. Today it is starting to return as proteomic methods including peptide detection in ancient samples and amino-acid specific stable isotope analyses are becoming more mature.

References

Anonymous. (2005). Insider: Look Before You Date. Archaeology 58(3, May-June 2005) https://archive.archaeology.org/0505/newsbriefs/insider.html

von Berg, A. (2002). Der Neandertaler aus dem Eifelkrater. Archäologie in Deutschland, 6 (November-December 2002) 18–19.

von Berg, Axel, Condemi, Silvana, & Frechen, Manfred. (2000). Die Schädelkalotte des Neanderthalers von Ochtendung/Osteifel—Archäologie, Paläoanthropologie und Geologie. Eiszeitalter Und Gegenwart, 50, 56–68.

Condemi, S. (1997). Preliminary study of the calotte of the Ochtendung cranium. Berichte zur Archäologie an Mittelrhein und Mosel, 5 (Trierer Zeitschrift Beiheft 23), 23-28.

Harding, L. (2005, February 19). History of modern man unravels as German scholar is exposed as fraud. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/feb/19/science.sciencenews

Justus, A., Urmersbach, K. H., & Urmersbach, A. (1987). Mittelpaläolithische Funde vom Vulkan Wannen bei Ochtendung, kreis Mayen-Koblenz. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 17(4), 409-417.

Lippl, Martina. (2024). Zwei spektakuläre Funde wohl gefälscht – Deutscher Archäologe im Fokus. Frankfurter Rundschau (online) November 29, 2024. https://www.fr.de/panorama/zwei-spektakulaere-funde-wohl-gefaelscht-deutscher-archaeologe-im-fokus-93433538.html

Rheinland-Pfalz Ministerium des Innern und für Sport. (2024). Archäologische Verdachtsfälle werden systematisch abgearbeitet. (press release) https://mdi.rlp.de/service/pressemitteilungen/detail/archaeologische-verdachtsfaelle-werden-systematisch-abgearbeitet

Richter, D., Klinger, P., Schmidt, C., van den Bogaard, P., & Zöller, L. (2017). New chronometric age estimates for the context of the Neanderthal from Wannen-Ochtendung (Germany) by TL and argon dating. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 14, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.05.032

Schlak, Martin. (2024). Der Knochenskandal von Koblenz. Der Spiegel (online) December 7, 2024. https://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/mensch/skandal-in-der-archaeologie-der-knochenfaelscher-von-koblenz-a-73db70b2-ae78-4b2c-9361-5dfdf529e744

Street, M., Terberger, T., & Orschiedt, J. (2006). A critical review of the German Paleolithic hominin record. Journal of Human Evolution, 51(6), 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.04.014