“Lucy”, superstar of evolution, at fifty

Today's science has broadened enormously since the 1970s but the iconic fossil still has an important place in understanding our ancient past.

November 24, 2024 is the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of the “Lucy” skeleton. I gave a presentation for local sixth-graders this week and as we ran through the different human relatives, I let them know about this special anniversary. They all knew who Lucy was. Many of them remembered the name that scientists had given her species: Australopithecus afarensis.

The fossil is famous around the world. She has traveled to some far-flung places, thousands of miles from the place her remains were found, the area of Ethiopia known as Hadar.

I didn’t ask the kids whether they knew the other names for the fossil. Most people near the Hadar site speak the Afar language, one of Ethiopia’s five official languages. The skeleton there is sometimes known as Heelomali, translated as “she is special”. But she has not returned to Hadar for many years. In Addis Ababa, where Amharic is the most common language, many people use the name Dinkinesh, translated in English as “you are marvelous”.

We will never know the name her family had for her. I do think she had a name, a vocal sign that others knew. A few things have been revealed about the vocal communication of Au. afarensis, especially from a young child’s skeleton from Dikika, not far from Hadar, which includes the hyoid bone. Configured like the hyoids of gorillas and chimpanzees, the evidence suggests that Au. afarensis had long-distance, resonant calls. Lucy’s calls would have been recognized by those she knew.

Her third molars hadn’t been more than a few years when she died. In other species of African apes, and in many human groups, female individuals who are reaching adulthood often transfer from the group where they were born into another group. She may have left her mother, possibly joining a nearby group where a sister already lived. Or possibly she continued to reside among her birth relatives, helping her to transition to her mature adult life sooner.

In either case, at her age, she likely had a child.

If a child was old enough when Lucy died, she may possibly have been fostered by other members of her group. Orphan gorillas above weaning age often survive their mother’s death; but orphan chimpanzees are not so successful. In these living species the most common caregivers are older siblings, and with Lucy’s comparatively young age it’s not likely she had a child old enough to substitute for mom. But Lucy's child may have had a wider network of care if—as some researchers have proposed—adult males were also helping to care for young children. Or if Lucy had still been resident in her birth group, where grandmother or aunts may still have lived.

What we know about her death suggests it was sudden. In 2016 a group of researchers studied the bones with microCT imaging for the first time, finding fractures on several of the skeleton’s bones that may have happened around the time of death. They suggested a catastrophic fall. Whatever caused Lucy's death, her body was quickly buried in a sandy stream bottom, apparently untouched by scavengers or carnivores, with the possible exception of a small puncture mark on her pubis. Maybe her family saw the fall and inspected the body, as many other primates do, perhaps even protecting it for some time.

Then again, maybe no one ever knew what happened until Donald Johanson and Tom Gray first saw the remains 3.2 million years later.

Because the Lucy skeleton is so widely known, there are a lot of misconceptions about why it was important. I was chatting with a journalist, and I pointed out that scientists had already been studying Australopithecus for fifty years when Lucy was discovered. Most of the features evident in the Lucy skeleton—the humanlike pelvis anatomy, canine tooth reduction, big molars and premolars, apelike brain size, small body size—were already well known in the South African Australopithecus record. The geological age of the Hadar fossils, spanning from around 3.4 million to 3.0 million years ago, was older than could be demonstrated at that time for any of the South African fossils. Still, they were far from the oldest known. Pieces of even earlier hominins had already been found during the 1960s in the southern Turkana Basin of Kenya.

“Why, then”, my interviewer asked, “was the Lucy discovery important? Why does Lucy get so much press?”

Marketing matters—especially when American science is involved. Investment in science in the postwar U.S. included several expeditions to Africa in search of human origins, led from institutions like the University of California, University of Chicago, and Harvard University. None of these efforts came close to the fossil richness found by South African researchers in their cave sites, or the finds made by Louis and Mary Leakey at Olduvai Gorge.

By contrast the Hadar expedition started on a comparative shoestring, led by young American and French researchers. In just a few years their work generated a sample of fossil hominins that rivaled any other known site in numbers and representation. The Lucy discovery in particular made an indelible image that seemed to mark a generational change in the progress of science. The team danced in the night to celebrate, listened to the Beatles, and looked to the stars.

The Lucy find would be just the beginning. In 1975 scientists located a place in the large Hadar field region with parts of the bodies of at least thirteen individuals near each other. They designated the place as AL 333, and the bones showed both the impressive variation of what may have been a single group. Combined with the evidence that Mary Leakey gathered from Laetoli, Tanzania, including the remarkable series of footprint trackways, research on the Hadar fossils sketched out a better understanding of how early human relatives moved.

Some of the most famous artistic images of Lucy show her creating one of the footprint trails from Laetoli, Tanzania. To be sure, Lucy herself never walked in that freshly fallen ash. She lived a thousand miles to the north, more than 300,000 years later. For these images, as in many other things, her role as the most complete individual known for her species enables Lucy to stand in as a representative for her southern neighbors.

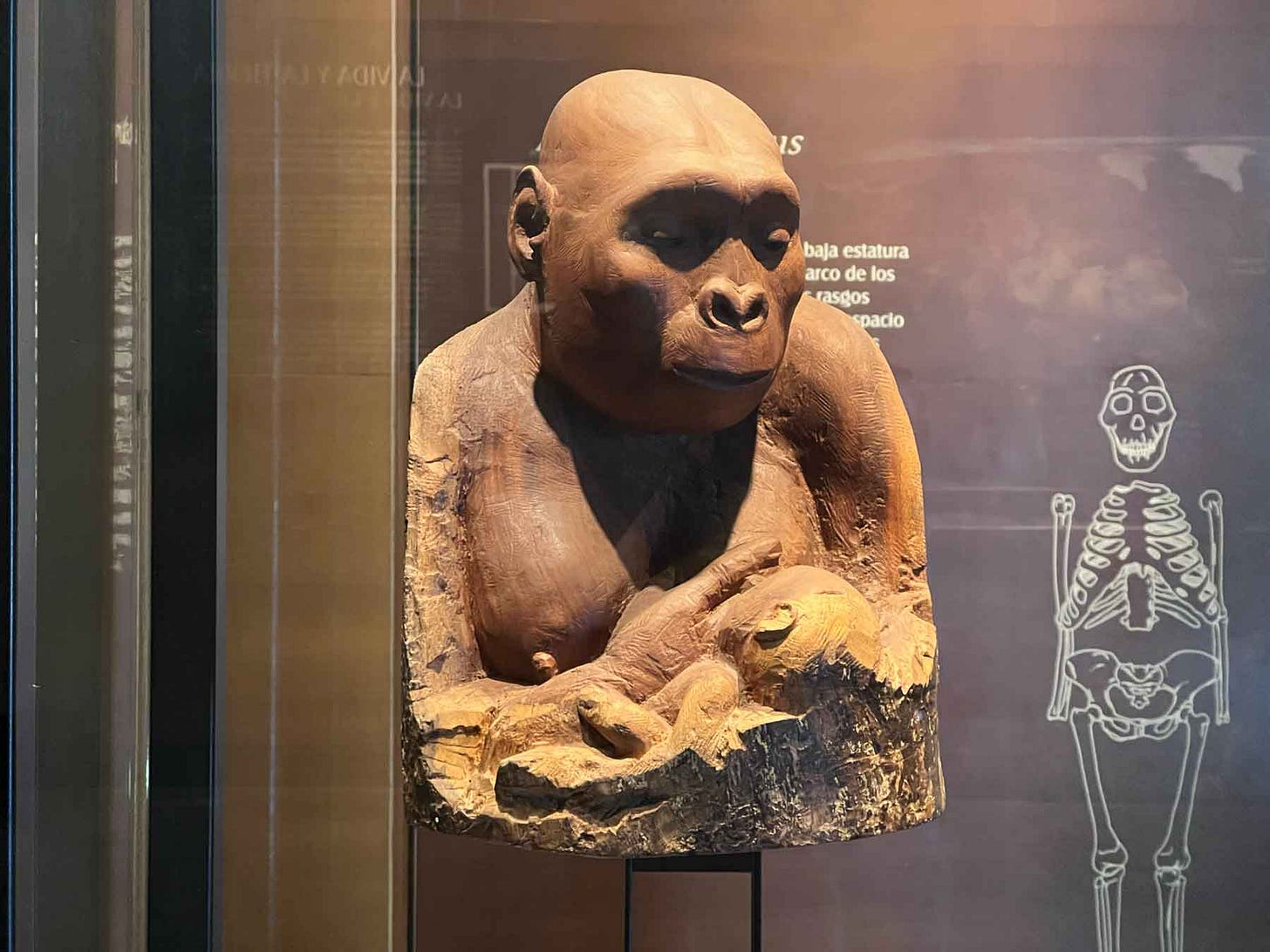

Laetoli has been just one of several fossil sites that have yielded information about Lucy's species. During the last quarter-century, other research teams have uncovered two impressive partial skeletons: the Kadanuumuu skeleton of a larger adult and the Dikika skeleton, who died as a child of around two or three years. At Hadar, too, more new discoveries emerged during the 1990s and later. Skulls such as the very large AL 444-2 and smaller adult AL 822-1 and AL 417-1 have removed some of the mystery attached to this part of the skeleton. The last of these, preserving much of a face and lower jaw, has become a common reference for artists as they create new “Lucy” life models.

How was Lucy connected with us? When researchers first defined Au. afarensis, back in the late 1970s, they hypothesized that all the known fossils from the same era would have belonged to a single lineage. In this way of thinking, Lucy was a grandmother of humanity.

At the time, there were other scientists who pointed to differences among the fossils in the teeth and in other parts of the bodies. Some thought that close relatives of our own, members of the genus Homo, may already have arisen at the time Lucy lived.

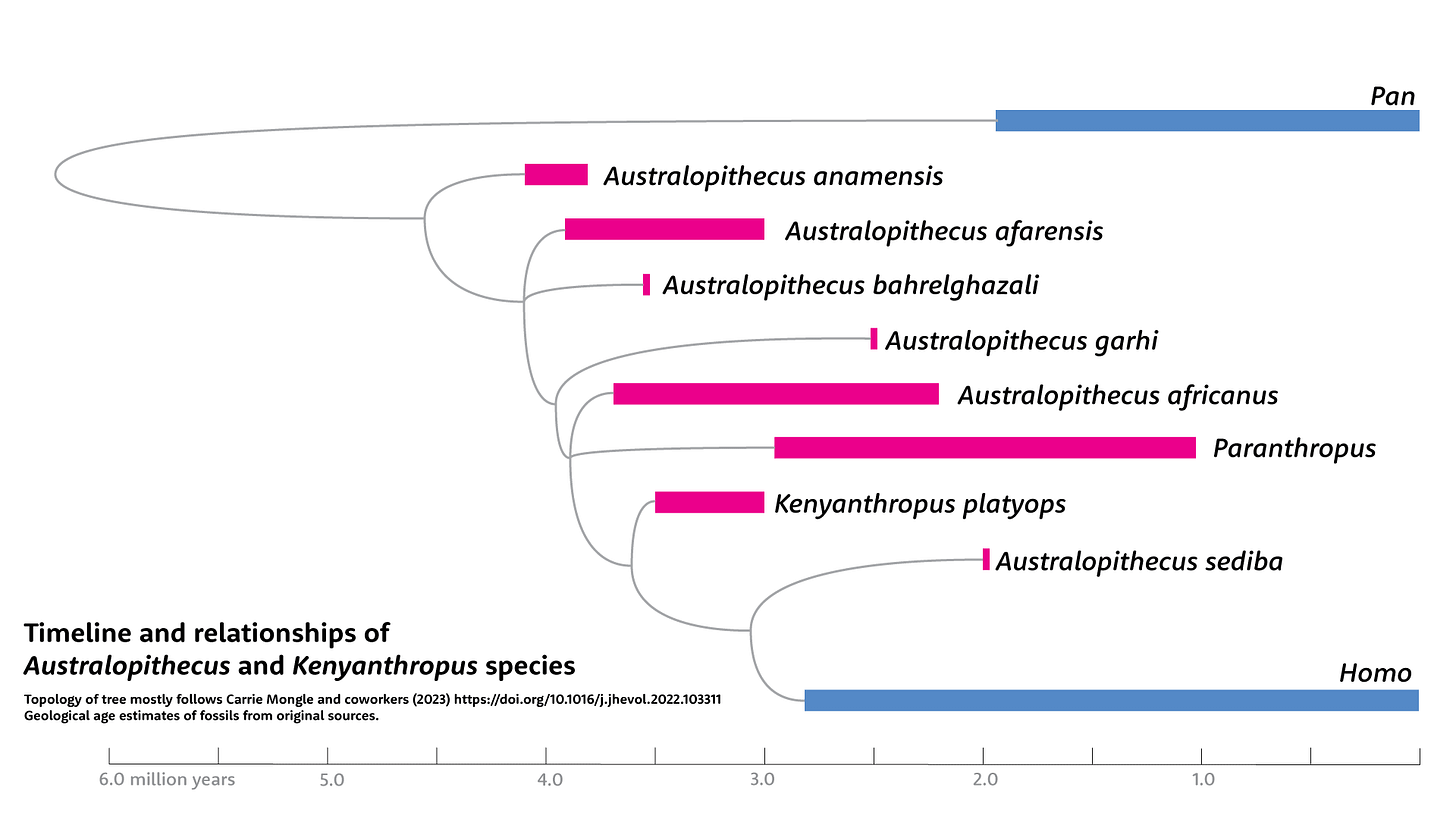

Our best understanding today is that Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, shares a common ancestry with us dating much earlier than Lucy’s lifetime, somewhere in the neighborhood of 4 to 4.5 million years ago. She, like most of the other fossils we study, were cousins of today’s people. The last common ancestors that she shared with today's humans were some of the earliest upright-walking hominins. Their new way of movement spurred other changes in lifestyle that enabled descendants like Au. afarensis to span the African continent.

Over the last quarter-century, several findings have led to the idea that Africa was crowded with hominins during Lucy's time, between 3.6 to 3.0 million years ago.

According to Yohannes Haile-Selassie, another of our relatives, Australopithecus deyiremeda, lived within the Afar region where Hadar and other Au. afarensis sites also occur.

In the Turkana Basin, scientists led by Meave Leakey attributed many fossils from the same era to Kenyanthropus platyops.

In South Africa, recent research by Darryl Granger and collaborators has suggested that some of the earliest finds of Australopithecus africanus may also fall in the same time range as Lucy's species.

There is even a tantalizing hint that these different species may sometimes have crossed the same landscape. The 3.6-million-year-old Laetoli footprint trails, attributed since their discovery to Au. afarensis, include one trackway made by peculiar-looking short and blunt feet. If these mark another form of hominin, as argued by Ellison McNutt and coworkers, then Au. afarensis and another species may have both seen each other passing.

Yet it would hardly be paleoanthropology if there wasn't debate. Each of these lines of evidence about other possible species has drawn its own share of detractors. Some researchers maintain that any notion of species diversity may be inflated. In a commentary last year, Zeresenay Alemseged included a more skeptical appraisal of the claims for various species, especially K. platyops and Au. deyiremeda. Other researchers have been strongly critical of the idea that any South African fossils are as ancient as Lucy's species.

I wonder whether it makes much difference. Geneticists during the last fifteen years have documented the extent of mixing among the latest branches of the hominin tree, showing that hybridization is a big part of today’s story of human origins. Our family tree had many vines extending from one branch to another. If Lucy herself sat in a tree and watched as a strange group came down to the opposite bank of the ancient Awash River, would she even have noticed the slight differences in their faces or their way of moving?

Maybe it's not Lucy who would have cared. Maybe it's us.

On my visit with the Madison sixth-graders, I showed some of the many images that artists have created of Lucy and her species. As the first of these images came on the screen, the whole class shrieked in surprise. I showed slides with varied reconstructions, following one after another like a parade of ancient faces. Each of them was a subject of fascination. Could we have really come from beings that looked so different from us?

We did.

All of us around the world today are so much more alike than any of us are with these distant ancestors and relatives, millions of years ago. Our heritage today traces back to them. Their lives, grandmothers, cousins, and sisters, made our lives possible. If Lucy could see us now, walking down to the river, I hope she might also feel how we honor her memory.

Notes: There are many excellent resources for people who would like scholarly reviews of research on Lucy and Australopithecus afarensis that are newer than the popular books of the 1980s. The 2009 review by William Kimbel and Lucas Delezene is now fifteen years old but summarized the first 35 years of research in one place. Last year's brief review in Science by Zeray Alemseged has an up-to-date snapshot of the various claims about species diversity in the Au. afarensis timeframe. This piece accompanied a research article by Philipp Gunz and coworkers, which pictured reconstructions of several Au. afarensis skulls and discussed the developmental biology of the species.

My own guide to the species of Australopithecus and its close relatives provides some more pathways to learn about these ancient hominins.

Guide to Australopithecus species

References

Alemseged, Z. (2023). Reappraising the palaeobiology of Australopithecus. Nature, 617(7959), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05957-1

Alemseged, Z., Spoor, F., Kimbel, W. H., Bobe, R., Geraads, D., Reed, D., & Wynn, J. G. (2006). A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature, 443(7109), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05047

Campbell, R. M., Vinas, G., Henneberg, M., & Diogo, R. (2021). Visual Depictions of Our Evolutionary Past: A Broad Case Study Concerning the Need for Quantitative Methods of Soft Tissue Reconstruction and Art-Science Collaborations. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.639048

Granger, D. E., Gibbon, R. J., Kuman, K., Clarke, R. J., Bruxelles, L., & Caffee, M. W. (2015). New cosmogenic burial ages for Sterkfontein Member 2 Australopithecus and Member 5 Oldowan. Nature, 522(7554), Article 7554. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14268

Granger, D. E., Stratford, D., Bruxelles, L., Gibbon, R. J., Clarke, R. J., & Kuman, K. (2022). Cosmogenic nuclide dating of Australopithecus at Sterkfontein, South Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(27), e2123516119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2123516119

Gunz, P., Neubauer, S., Falk, D., Tafforeau, P., Le Cabec, A., Smith, T. M., Kimbel, W. H., Spoor, F., & Alemseged, Z. (2020). Australopithecus afarensis endocasts suggest ape-like brain organization and prolonged brain growth. Science Advances, 6(14), eaaz4729. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz4729

Haile-Selassie, Y., Gibert, L., Melillo, S. M., Ryan, T. M., Alene, M., Deino, A., Levin, N. E., Scott, G., & Saylor, B. Z. (2015). New species from Ethiopia further expands Middle Pliocene hominin diversity. Nature, 521(7553), Article 7553. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14448

Kimbel, W. H., & Delezene, L. K. (2009). “Lucy” redux: A review of research on Australopithecus afarensis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 140(S49), 2–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21183

Leakey, M. G., Spoor, F., Brown, F. H., Gathogo, P. N., Kiarie, C., Leakey, L. N., & McDougall, I. (2001). New hominin genus from eastern Africa shows diverse middle Pliocene lineages. Nature, 410(6827), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/35068500

McNutt, E. J., Hatala, K. G., Miller, C., Adams, J., Casana, J., Deane, A. S., Dominy, N. J., Fabian, K., Fannin, L. D., Gaughan, S., Gill, S. V., Gurtu, J., Gustafson, E., Hill, A. C., Johnson, C., Kallindo, S., Kilham, B., Kilham, P., Kim, E., … DeSilva, J. M. (2021). Footprint evidence of early hominin locomotor diversity at Laetoli, Tanzania. Nature, 600(7889), Article 7889. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04187-7