Lida Ajer, early modern human remains in island Southeast Asia

A site first investigated by Eugene Dubois is rediscovered by Kira Westaway and collaborators.

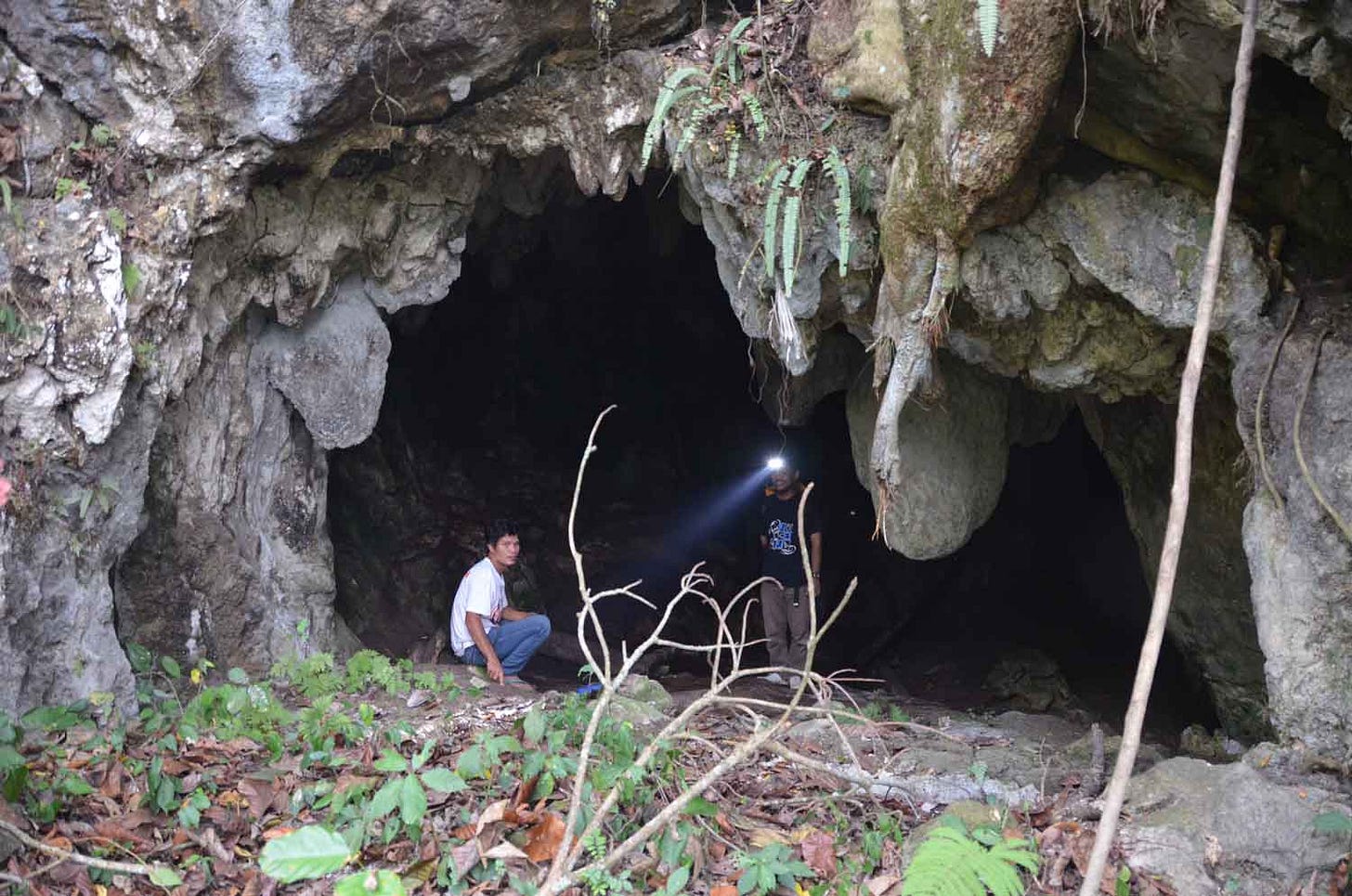

In August of last year, Kira Westaway and colleagues published new dating results from Lida Ajer, Sumatra: “An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73,000–63,000 years ago”. The cave has a fossil-bearing breccia that was excavated by Eugene Dubois during the late 1880s.

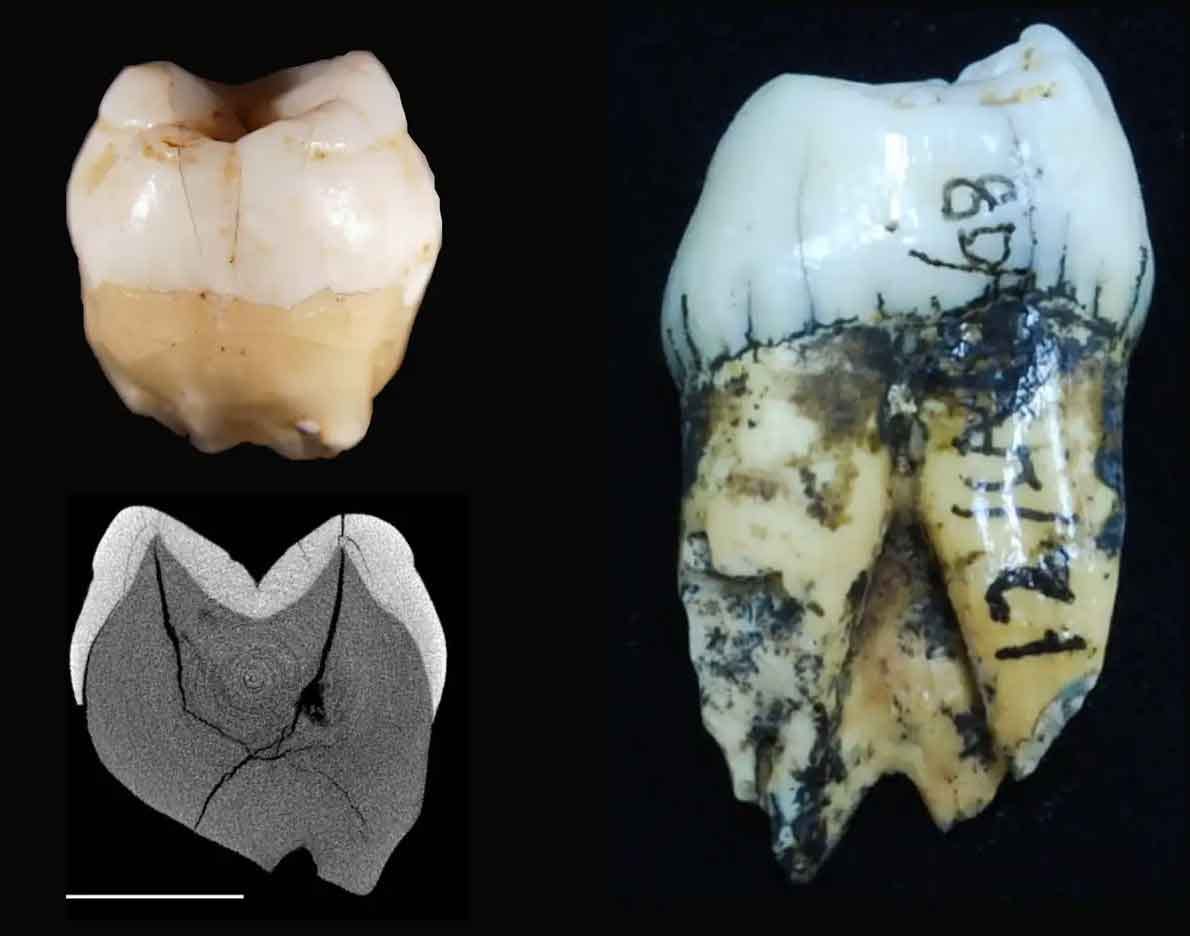

Dubois lost interest in excavating Sumatran caves because he believed the fossils were too recent to document the “missing link” he sought. In 1948, D. A. Hooijer described some of the orangutan teeth from Dubois’ collection from Sumatra, along with two human teeth from Lida Ajer. He concluded that these two teeth, an upper central incisor and a likely second upper molar, were indistinguishable from modern human samples.

Westaway and colleagues were able to relocate the Lida Ajer cave by using Dubois’ notes, while they have been unable to find other caves that Dubois investigated.

Gilbert Price, one of the team members, has put a short video on YouTube giving some context of the team’s initial reinvestigation of the site.

It is great to be able to see the site’s surroundings and a bit of the fossil context in this way.

Hooijer had speculated that the fossil assemblage might have originated as a porcupine accumulation. The collection is nearly entirely teeth and some of them–including the two human teeth–bear evidence of porcupine gnawing. Westaway and coworkers agree with this assessment and further suggest that the fossil-bearing breccia may have flowed into its current location as a mass and later lithified.

The conclusion that the teeth are modern human rather than some archaic human form or Homo erectus is clear enough.

The Lida Ajer teeth are smaller than fossil orangutans and east and southeast Asian Homo erectus/archaic Homo sapiens (Extended Data Fig. 3). They show greater affinity to east Asian Late Pleistocene H. sapiens than to southeast Asian Late Pleistocene to mid Holocene H. sapiens (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). The relative enamel thickness of the incisor is most similar to mean values for modern humans, and exceeds the extant orangutan range (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5). Relative enamel thickness of the molar is intermediate between mean values of living humans and living and fossil orangutans. Discriminant function analysis of molar enamel–dentine junction morphology classifies it as H. sapiens (Extended Data Figs 4, 5, 6). Both teeth have a simple external morphology typical of H. sapiens. They lack traits that characterize east and southeast Asian H. erectus/archaic H. sapiens and Homo floresiensis. Furthermore, derived H. sapiens features are found in both teeth, such as incisor double shovelling (Supplementary Information). The combination of their small size and external and internal morphology demonstrates that they are anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

Westaway and coworkers have added substantially to Hooijer’s description by adding the microCT observations, including the enamel-dentin junction (EDJ) and data on enamel thickness. These teeth do not differ from the teeth of Late Pleistocene East Asian human samples, which include the very early teeth from Tam Pa Ling, Laos, and Liujiang, China, along with somewhat later Chinese, Vietnamese, and other archaeological sites.

Based on the authors’ model of site formation, they assume that the breccia deposit formed in a short period of time and does not sample fossils from across substantial geological time. They obtain estimates of geological age from the breccia in four ways: Uranium series dating of flowstones and other speleothem samples, uranium series dating of fossil teeth, ESR dating of the fossil teeth, and red thermoluminescence dating of quartz grains in the breccia.

All of these methods arrive at a similar picture. The U-series dates on the fossil teeth provide minimum ages, and these are all over 40,000 years ago, and most age estimates including ESR and red TL within the range from 80,000 to 60,000 years ago. The flowstones that bracket the top and bottom of the authors’ stratigraphic profile of the breccia are 71,000±7 and 203,000±17,000 years old. None of the U-series dates from within the breccia are nearly as old as the underlying flowstone.

As I read the paper and supplementary information, I kept looking for documentation to convince me that Dubois actually collected the two human teeth from within the breccia in the stratigraphic position shown by the authors. To me, the provenience of these two teeth is a critical question. I don’t have any specific reason to doubt that they come from within the breccia where they are reported, but with any site excavated so long ago, we do need to ask the question. The human teeth have no direct date, look like those of modern humans, while lacking the mineral staining seen on some of the faunal remains that they have pictured.

The cave has no evidence of stone tools or other artifacts. The authors discuss this in their supplementary text:

No evidence of archaeology was observed in the cave or surrounding region. Hooijer did “not consider the two teeth described above as evidence of human inhabitation in the prehistoric Sumatran caves”. Hooijer’s comments were made in reference to what he considered a non-occupation cave. No excavations have been conducted in the front of the cave, and whether or not prehistoric peoples used the cave remains to be demonstrated. Nevertheless, the assemblage reflects the fauna that were present on the landscape, humans included. Furthermore, we note the presence of human remains but an absence of archaeological evidence is a common feature in other Asian caves, such as Thum Wikin Nakin in Thailand, Punung in Java, and Fuyan in southern China.

It’s typical to hear that archaeological sites vastly outnumber sites with hominin remains. From that generalization, it might seem reasonable to suppose that archaeological sites document the dispersal of human populations with more fidelity than hominin bones and teeth.

But most time intervals are poorly represented by archaeological sites in most regions of the world. Southeast Asia and island Sundaland have a very sparse archaeological record, even though hominins were likely there in large numbers through most of the Pleistocene.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have expressed many ideas about that sparse record. Some of the area was forested during large spans of time, and many anthropologists have expressed the idea that hominins could not penetrate forested habitat effectively until the last 20,000 years.

Lida Ajer is the earliest hominin discovery in rainforest anywhere in the world [but see UPDATE below]. I don’t think that’s because hominins weren’t in these forests, I think it’s because these areas have not been explored with the intensity of lake edge sites and caves in arid and temperate habitats.

During the last fifteen years, there have been remarkable discoveries in island and mainland Southeast Asia, and I expect that to continue as people keep going.

UPDATE (2018-01-08): I have an e-mail from John de Vos informing me that I should investigate the Punung site on the island of Java.

Punung has a rainforest fauna dated to around the last interglacial (in other words, around 120,000 years ago) and a single human premolar, which is similar to modern humans in its measurements.

I’ll follow up with more information on Punung in a separate post.