Research highlight: Burials by Homo naledi

After two years of intense reviews and revision, the work on burial evidence from this ancient hominin finds acceptance.

Citation: Berger, L. R., Makhubela, T., Molopyane, K., Krüger, A., Randolph-Quinney, P., Elliott, M., Peixotto, B., Fuentes, A., Tafforeau, P., Beyrand, V., Dollman, K., Jinnah, Z., Gillham, A. B., Broad, K., Brophy, J., Chinamatira, G., Dirks, P. H., Feuerriegel, E., Gurtov, A., … Hawks, J. (2025). Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi. eLife, 12 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.89106.2

This week the journal eLife released a new editorial evaluation of our team’s work on burial evidence from Homo naledi. The reviews and editorial assessment are remarkably positive. All of them accept that burial of remains by Homo naledi is a strong explanation for what we have found. They suggest some important lingering questions, which themselves are great suggestions for follow-up work.

One of the really exciting pieces is that some of that follow-up work is already near completion and I expect we will be able to share some of that research very soon.

This research has been a long journey. This latest work relies on data that we started to gather back in 2013, with important updates from fieldwork in 2017, 2018, and 2022. We targeted these explorations to find answers to striking questions that we had been asking from the first days of the Homo naledi discovery.

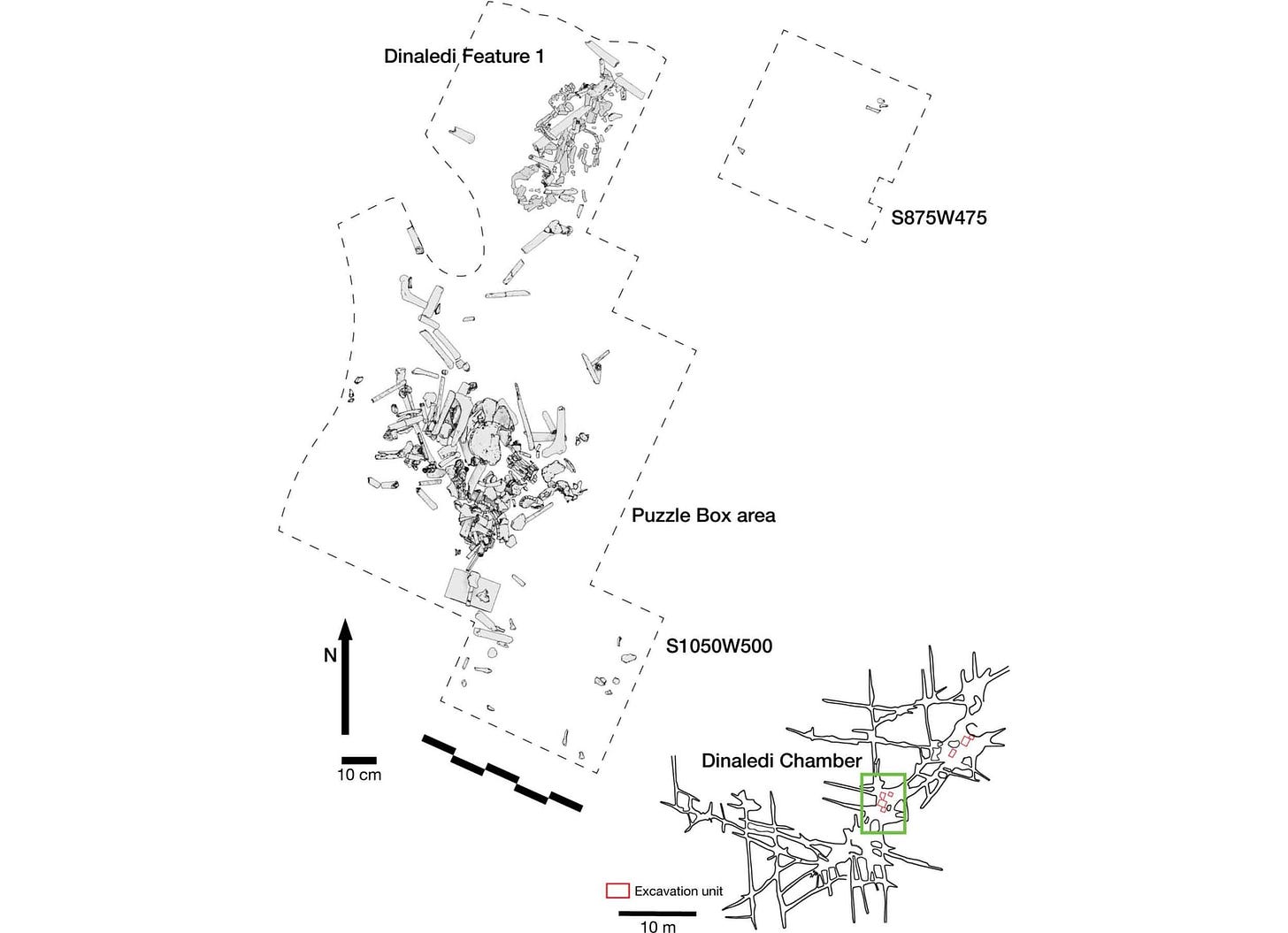

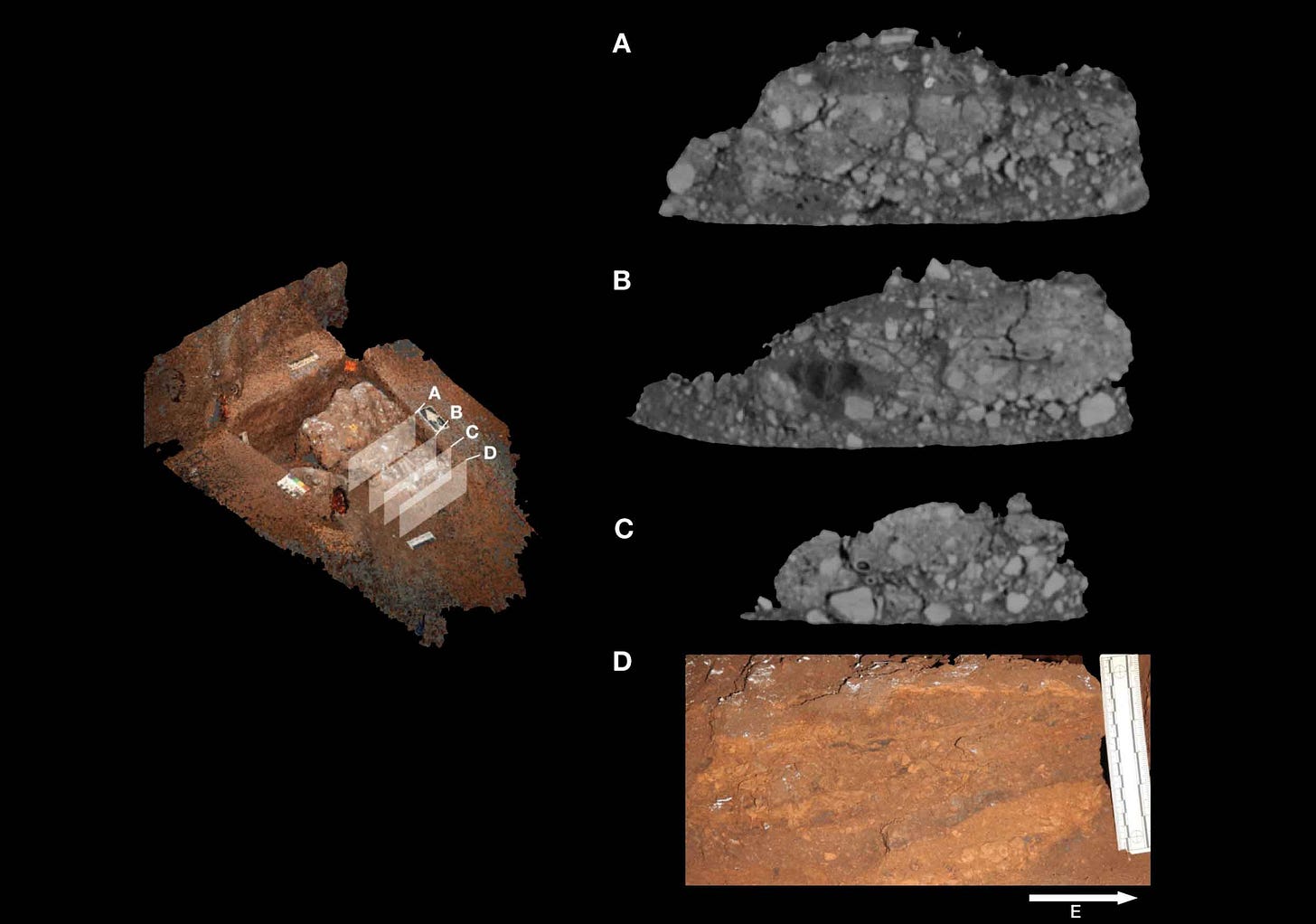

Investigating those answers took the collaboration of a large group of researchers, with 37 coauthors contributing to the study. They include a sequence of incredible teams of explorers and excavation specialists over the last 12 years. We also had teams of people working in the laboratory on the analysis of the skeletal remains and their spatial positioning. A team working with virtual data, including from synchrotron imaging, enabled us to look inside a significant sediment block, revealing fossil material and associated sediment in original context.

Telling the whole story of how we began to appreciate the hints of Homo naledi behavior is much more than one post. There remain quite a number of scientific questions that I’ll highlight in coming weeks.

Here, I want to reflect on the strength of evaluation of this work and how comments and advice from many other experts have shaped the final result. In this, I can of course only give my own perspective and not the perspectives of every one of my collaborators. Coming to this point has been a huge investment from reviewers, editors, and many colleagues through the public channels of comment.

The eLife process

The eLife model adopted in early 2023 differs from the model of review and editorial decisions in most academic journals. At eLife, submitted manuscripts are available to the public on bioRxiv preprints before they undergo any review, and the role of review is to provide expert assessment alongside the preprint, not to “accept” or “reject” it from publication. This is by design an iterative process. Authors can respond to reviews, provide more context, revise their manuscripts and release an updated preprint for evaluation.

Since the whole review process unfolds in public, all the reviews and responses are part of the public record of the research. This is a remarkable strength of the model. Anyone who reads the research can see current evaluations by experts, even as the authors may continue to resolve questions that remain.

Our team has worked with eLife since the first publication on Homo naledi in 2015. We have a great history with the journal, and some of the work I'm most proud of has been published there.

But that work was published under the previous, more traditional, model. The new preprint assessment model was a little intimidating. Could we release a preprint in paleoanthropology in this way, with all the attention it would bring, and not face a storm of criticism? We committed to following the process and working with the reviewers and editors to the end.

At this point I can say that the model worked extremely well. One of the great things about preprints is that not only reviewers and editors, but a very broad array of researchers can choose to engage with the work and provide comments. Over the last two years many people—scientists, academics, and many other interested people—have weighed in with ideas about how the first preprint could be better. Some of their ideas basically repeated the eLife reviewer comments, which themselves were remarkably thorough. Many people added new perspectives of their own that would not have emerged through the normal highly-secretive process of review in most journals.

For our revised preprint, we were able to draw from all these comments. We provided some new analyses to answer specific questions that reviewers asked. People wanted us to add a lot more information from our prior work to help understand the context of the remains in the cave system. That advice helped us to tell the whole story from the beginning, which has made for a stronger paper.

The end result of this revision is a richly detailed presentation of the evidence. The main text and figures take up more than 150 manuscript pages, and the supplemental information added up to more than 100. Up from a relatively small number of main text figures, the revision answering all comments includes thirty.

This has been a highly interdisciplinary process of research. Different parts of the evidence were assessed by experts in different areas of study. That proved to be one of the biggest challenges in the review of the work. Each reviewer brought a different kind of expertise to their assessment. In a few cases they contradicted each other, because an explanation that might seem to work for one kind of evidence could not work for others.

What we had to keep at the forefront at all times is that all the different lines of evidence must address the same events, the same history for these fossils and sediments. I think in the end, the reviews enabled us to revise the work in a way that keeps this interconnection of all the lines of evidence as our guiding star throughout.

Natural and cultural

Many people, including the eLife reviewers and editor, asked us to reframe the paper. They wanted us to present the hypothesis of a “natural” process of deposition, and then use the evidence to reject that hypothesis. The implication was that a “cultural” hypothesis was something extraordinary, only to be accepted after we excluded every noncultural alternative.

The duality of “natural” versus “cultural” would lead us to many new insights as we built our revision. We discussed the reviews and comments, and we found that we could not agree with the idea that “natural process” is the right null hypothesis for this work. We checked the references we had cited, and we found that almost nobody else who has written about burial in modern humans or Neanderthals agreed with that idea, either.

And yet, as we worked to add our own previous research results into the paper’s introduction, we saw that we had written about the Homo naledi skeletal remains in exactly this way. In our earlier papers we had explored almost every kind of noncultural phenomenon to understand what we were seeing. The results of those earlier papers ruled out carnivore involvement, and water transport, and the idea that Homo naledi individuals had been trapped after falling into the cave. We were left with a cultural hypothesis: Homo naledi bodies were likely transported by other members of their group.

That same evidence showed highly selective and localized reworking of the bone materials after they had been deposited. We kept trying to find “natural” explanations for this reworking. Before starting on this new paper, we never considered even for a moment the simple idea that what we were seeing could be easily explained if Homo naledi had dug into the sediments. In retrospect it was striking that we missed this. But the notion that “the null hypothesis is natural” had been so much of a barrier that we didn’t at first recognize when we had left it behind.

Personally, this area of “natural” versus “cultural” has energized me to think about many aspects of the hominin record in ways I hadn't considered before. This topic has already led to many new insights for our team that have spun off into new projects. I’ll write more about this in coming posts.

Would I change the process?

Over the last couple of years, I’ve had a few anthropology and archaeology colleagues ask me whether I would change this process. Some of them think that the very concept of preprints is a terrible idea. They say that researchers should stay silent about their work before a journal has completed a traditional process of review and publication. More of my colleagues like preprints but don't release them for their own work. What they really don't like is having their work placed for everyone to read alongside tough reviews.

I just don’t see it that way. I’ve been in paleoanthropology for a long time. You can't do anything interesting without facing some challenging reviews.

Heck, even after a “high-profile” paper runs the gantlet of review and publication, how many of those will go six months without having some group of critics publish their own post-publication review in another journal? How many journals bulk up their citation counts with “News and Views”-type commentaries that challenge or dismiss published work?

Even when our team followed the open process at eLife, in which anyone can give a public comment on a preprint, we nevertheless had a few colleagues who thought they would bulk up their citation counts by doing “reviews” of our work in other journals! That was one weird moment when I saw the first of those.

All this has helped me to see that the real problem with traditional journal reviews is non-transparency. In the past, one or two tough reviews could keep your work from being read by anyone for years. It's happened to me many times, and I'm not an unusual case. The perfect storm of bad outcomes is when one team of researchers holds back their data hoping for that “high-impact” publication. In those cases, one or two reviewers or editors can keep the rest of the field spinning their wheels.

We don't have to do that anymore.

Public-facing evaluation of research makes much more transparent where discrepancies and disagreements of interpretation exist. The facts will come out in the end, they always do. What we need to support as scientists is for the work to be as transparent as possible, from observation to interpretation. If we can eliminate the culture of fear around releasing new research and data, that would go a long way toward making research more reliable.

I’ve certainly taken that approach with this blog for the last twenty years. I can say from experience that it makes a difference when experts formulate and write comments about research for the public to read. I am a scientist, not a journalist. I follow my own priorities about what I think is important: whether data and interpretations are reliable, how they raise new questions for future work, how they relate to what has come before.

When I work with journalists, and media, and documentary productions, I give my best guidance about how new research relates to previous work, whether it is really changing ideas or just adding new detail, and how reliable the interpretations may be based on the data.

There are very few in this field who are providing their insight to the public in this way. Their work helps both experts and nonexperts to understand better the strengths and limitations of what we know. We need much more of this process to be open. Urgently.