An unusual rate of dental chipping may give clues about Homo naledi's diet

Research by Ian Towle and coworkers finds that Homo naledi may have been eating foods with lots of grit.

I’d like to point everyone to this new article that may give some insight into the diet or behavior of Homo naledi: “Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi”. Ian Towle from Liverpool John Moores University examined the H. naledi dental sample last year and, with his colleagues Joel Irish and Isabelle De Groote, he has shown something very interesting about Homo naledi in comparison to other primates: They chipped their teeth a lot.

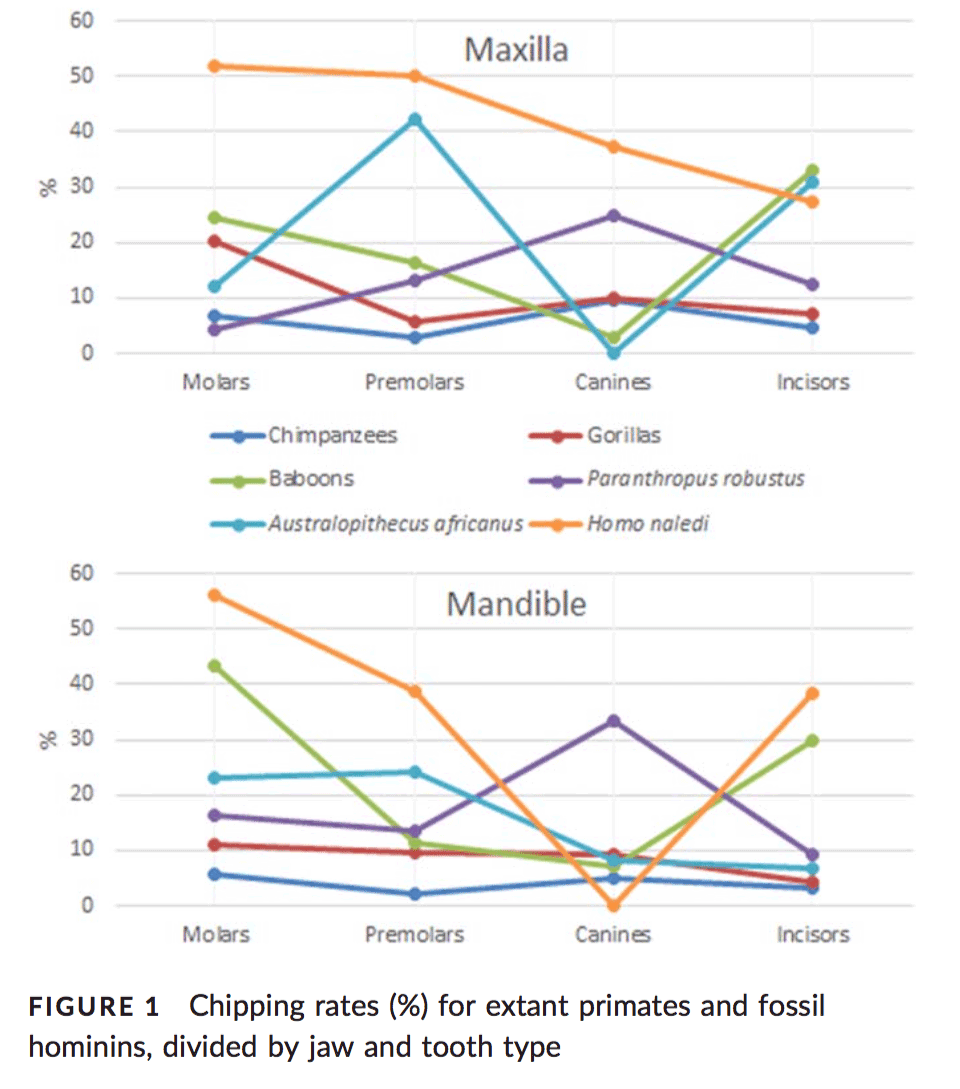

Figure 1 from the paper tells the story:

Compared to chimpanzees and gorillas, extinct hominins like Au. africanus and Paranthropus robustus crunched on things that chipped their teeth a lot more—for mandibular molars, 25% in Au. africanus, versus only 10% for gorillas. For maxillary molars, gorillas crunched a bit more, and P. robustus surprisingly little. So there seems to be a good bit of noise in the data. But H. naledi puts the apes and other hominins to shame, with 50% chipping in maxillary molars and premolars, 60% in mandibular molars, and 40% in mandibular premolars.

Whatever it was eating or doing with its postcanine teeth, H. naledi was chipping them a lot. And those chips are not microscopic things, they are obvious on visual inspection of the teeth:

In other words, these are macroscopic aspects of tooth wear. We have seen on the teeth of H. naledi that there is a very high wear differential between teeth, and they seem to really have distinctive patterns of wear. Towle and colleagues point out that it is not just anything that yields this kind of chipping, it is seen predominantly in populations that incorporate high amounts of grit into their normal diet. For example, baboons:

The extant primate samples may offer more useful comparisons for H. naledi. For example, in a microwear study by Nystrom et al. (2004), baboons in dry environments were reported to consume large amounts of grit. In the present, combined sample of hamadryas and olive baboons, we found similarities to H. naledi, with frequent small chips and a higher rate of chipping among posterior teeth relative to anterior teeth.

And humans that eat things that sometimes contain shell fragments:

A Late Woodland sample from Cape Cod in the U.S.A. has a pattern like H. naledi in terms of frequency and position (McManamon, Bradley, & Magennis, 1986). The overall frequency is 43% and molars are reported as the tooth type most prone to chipping, with interproximal surfaces most affected. Unfortunately, frequencies for tooth types and positions in that study are not reported. McManamon et al. (1986) suggest that the cause of this patterning was the incorporation of sand, gravel, and/or shell fragment contaminants into the food.

Towle and colleagues note also that the Taforalt sample from the Epipaleolithic of Morocco also has high rates of dental chipping, again thought to relate to the incorporation of shells and fruit stones into the diet. These are high quality food sources that have small, hard objects within them.

The fact that there are human samples with frequencies of chipping comparable to that in H. naledi makes this a bit less puzzling. I would suggest we are looking at dietary adaptability within a population that has a relatively high energy density in its foods. That idea is consistent with the fact that H. naledi has relatively small tooth sizes, despite having substantial chipping rates.

What will be interesting is to see what the microwear texture is like in H. naledi. The sampling for microwear has been done, and our team is now working on assessing it. Thus far, microwear studies have given counterintuitive results as applied to robust australopithecines like P. robustus and others like Au. africanus. “Nutcracker man” evidently wasn’t cracking nuts. That result is holding in this study according to chipping—when you look at the most robust dentitions here, in P. robustus, they have among the lowest rates of dental chipping.

Anyway, it is exciting to see these clues emerge. The picture from dental chipping is remarkably consistent across the H. naledi sample, and it is telling us something very interesting about the diet or other uses of the teeth in this species.