An enormous sample sheds light on the Denisovan ancestry of people in Iceland

Laurent Skov and coworkers have measured the very small amount of DNA shared within the Iceland population from Denisovan ancestry and they discuss several scenarios for how it may have gotten there.

Last week in Nature, Laurits Skov and collaborators from Aarhus University and from Kari Stefansson’s research group in Iceland gave a high-resolution look at Neanderthal and Denisovan introgression in the Iceland population. The title of their paper is: “The nature of Neanderthal introgression revealed by 27,566 Icelandic genomes”.

I see this paper as a first step in a new phase of research. Up to now, samples of human genomes used in phylogenomic analysis have been limited in number. The 1000 Genomes Project samples include a hundred or so individuals from just a few populations. Most other studies have had much smaller sample sizes. Ancient genomes by their nature are limited in number.

Small samples do enable geneticists to answer some questions with high confidence. These are the questions where ancient people were very different from each other, and from people living today. “Did they mix at all?”, or “Assuming total isolation between them, when did their populations start to diverge?” But when you start to specify just how strict the assumptions must be to do the math, you start to see how unsatisfying the answers to such simplistic questions really are.

Truly large samples allow us to answer questions that involve small levels of difference between ancient and modern people. Ancient humans were like us in most ways. Nearly all their phenotypes overlapped with those of living populations. They were emphatically not subject to “total isolation”, they mixed repeatedly. How often did they mix? How important was that mixture to their evolution? Those questions take big samples to start to answer.

I’m going to spend some time evaluating this research and pulling out some of the new directions in separate posts. Skov and coworkers are able to identify the fine-scale similarities between haplotypes in the genomes of living people and in three high-coverage ancient genomes. In this case that includes the so-called Vindija and Altai Neanderthal genomes and the Denisova genome.

In this post, I want to focus on the Denisovan component of ancestry.

The advantages of a large-sample approach are abundantly evident when considering the very small amount of genomic DNA that Iceland people have from Denisovans. Skov and coworkers quantified the very small amount (0.1%) of DNA shared within the Iceland population from Denisovan ancestry and they discuss several scenarios for how it may have gotten there.

Finding Denisovan ancestry in western Eurasian samples is not a first-ever result, and similar small fractions of this ancestry have been found in other recent studies. Earlier this year, Anders Bergström and coworkers reviewed the variation found from whole-genome sequencing of many Human Genome Diversity Project samples, and quantified Denisovan-like haplotypes in many populations, including New Guinea populations. Their figure from the supplementary information shows the amount of each population’s genome that they infer to be Denisovan:

Bergström and coworkers estimated that 2.8% of the ancestry of the highland New Guinea sample in their study came from Denisovans. As visible in the figure, the amount of genome identified with high confidence as Denisovan is less than the overall estimate, and amounts to around 25 million base pairs per genome in the highland New Guinea sample.

[As an aside, it is not obvious how this result reported in the Bergström et al. supplement connects to the estimated fraction of ancestry. Twenty-five million base pairs is less than one percent of a genome (and less than half a percent of a diploid genome). For my discussion here, I’m just looking at the fraction of this amount as estimated for other populations.]

If we look at western Eurasian populations here, like French or Orcadian, around 0.1 on the x-axis scale, or 1 million base pairs, are estimated to be Denisovan. Assuming the same 3:1 ratio that seems to apply to the New Guinea sample in that paper, this would suggest around 0.1 percent of the genomes of these samples are Denisovan in origin.

[As another aside, did anybody else notice that the Bergström et al. supplementary figure has more Denisovan ancestry inferred in the San sample than in French? Something with incomplete lineage sorting is surely going on that hasn’t been well quantified here. One problem is that Bergström et al. seem to have assumed near-zero introgression in African populations, and Joshua Akey’s group showed that this assumption is incorrect. ]

Bergström and coworkers (2020) is the most recent analysis of Denisovan introgression into Eurasian populations, but some earlier work from Joshua Akey’s group provide somewhat more resolution of these issues. In 2018, Sharon Browning and coworkers examined Denisovan ancestry in Eurasian populations and inferred two Denisovan source populations for introgressed haplotypes in most Asian populations. I’ll return to this paper below. Earlier this year, Lu Chen and coworkers looked at Neanderthal ancestry in sub-Saharan African samples. In the course of this analysis, they also quantified Denisovan-like genome segments in 1000 Genomes Project samples. They found a similar amount of Denisovan-like haplotypes in African and Eurasian population samples, around 1 megabase on average. Chen and coworkers interpreted this result as a baseline for incomplete lineage sorting for their purposes, which was to identify Neanderthal ancestry in sub-Saharan Africa. But it is interesting in the context of identifying true Denisovan introgression in all these populations.

So the Iceland result found by Skov and coworkers, using a vastly bigger sample of living people, seems to be pretty close to what other populations in western Eurasia have. If anybody was wondering if Denisovan ancestry in Iceland is a sign of a transoceanic migration from Melanesia to Iceland, that hypothesis isn’t necessary.

OK, let’s look more closely at what Skov and collaborators find from their enormous Iceland sample. This is a figure showing the distribution of introgressed haplotypes across all the chromosomes:

This figure is one of those nutty diagrams that shows a logogram of every chromosome split into 4 panels that each are marked up with colored blocks representing the location of introgressed haplotypes. Together these add up to around 40 percent of the genome with some evidence of introgression within the modern sampled individuals.

According to the results, the Iceland population has something like 0.1 percent Denisovan-like ancestry across their genome. Skov and coworkers went to some effort to try to understand where this Denisovan component came from.

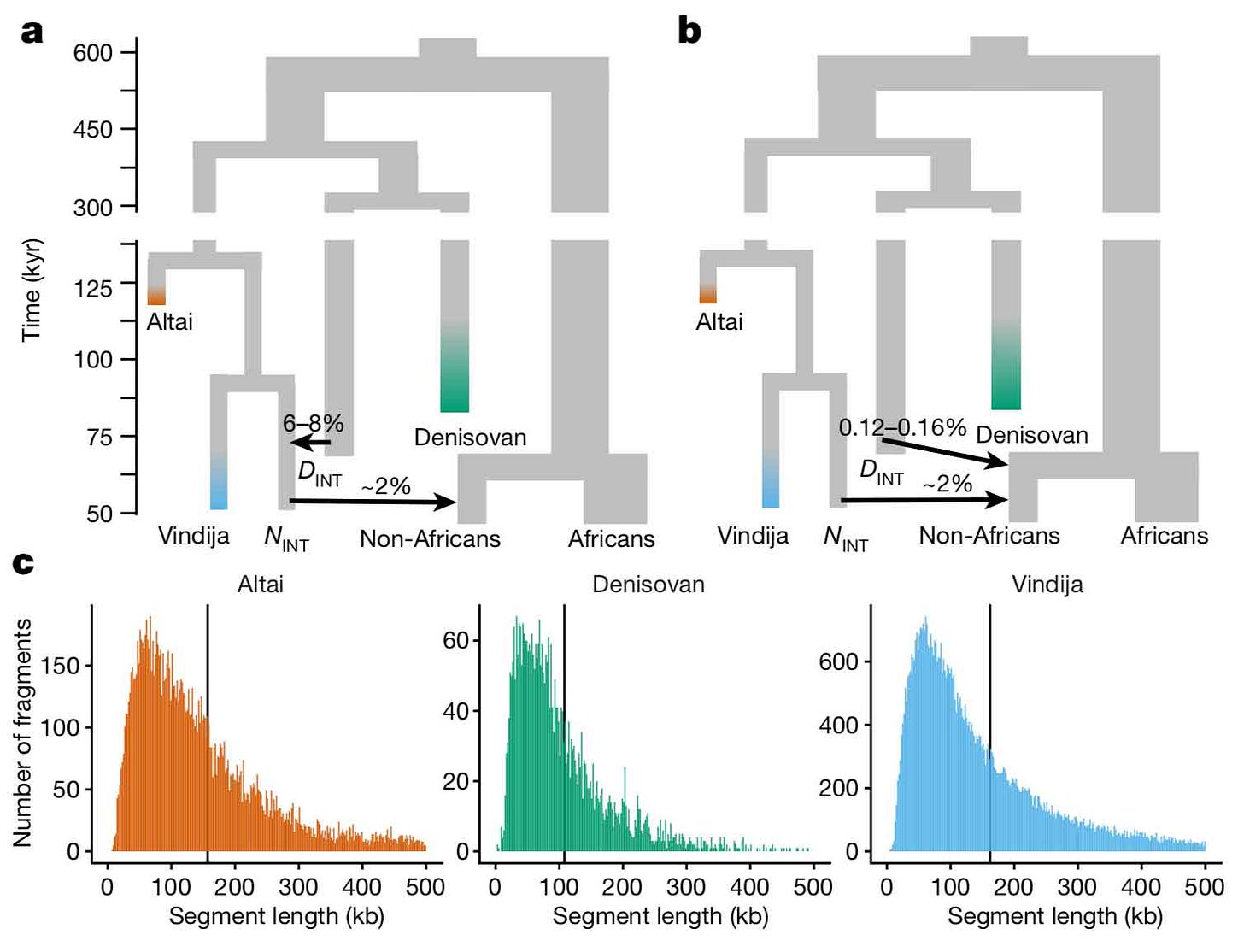

Denisovan ancestry may come from direct mixture of early modern people with a Denisovan group; or alternatively, Denisovan ancestry in Icelanders may have come indirectly from Denisovan mixture with Neanderthals that happened before early modern humans mixed with Neanderthals. Skov and coworkers provide a figure that shows the difference between the direct and indirect models:

Notice that in the direct model, non-African peoples get around 0.12-0.16% of their ancestry directly from a divergent Denisovan group. In the indirect model, the “introgressing Neanderthal” group gets 6-8% of its ancestry from Denisovans, and then gives 2% to the ancestors of today’s non-African peoples.

Because the Denisovan component of ancestry is so small, it is difficult to test the difference between these scenarios. The two scenarios (direct versus indirect) do predict slightly different things about the Denisova-like haplotypes. If these all came indirectly into modern humans from a Neanderthal population after Denisovan-Neanderthal introgression, then recombination should have connected many of them directly to haplotypes that otherwise resemble Neanderthals, creating a recognizable pattern. This puts a constraint on how early the Denisovan-Neanderthal mixture could have been. But if such Denisovan-Neanderthal introgression happened within the period just before modern-Neanderthal introgression, it would be very hard to tell the scenarios apart. And the sizes of these populations matter – the survival of distinct Denisovan lineages after introgression within a Neanderthal population is more likely in a larger population than a smaller one. All this means that there are a lot of ways that a different sequence of events might lead to a similar outcome.

One thing that the study concludes for certain is that this Denisovan component of Iceland genomes does not come from incomplete lineage sorting alone. These are not ancient African genetic haplotypes that merely resemble Denisovans. They really did come from Denisovans at some stage of prehistory.

A second thing that is clear is that the Denisovan-like haplotypes in Icelanders do not come directly from the Denisovan population sampled at Denisova cave in the Denisova 3 high-coverage genome. Skov and coworkers were able to examine the extent of allele sharing between the Denisova-like haplotypes in Icelanders and the Denisova 3 genome itself:

We find that the amount of derived variant sharing is compatible with a scenario where the introgressing Denisova splits from the sequenced Denisova around 300-350 kya.

That’s a fascinating conclusion. The extent of diversification within Denisovans that this would represent is as great as the greatest divergences among surviving modern human populations that survive today. Their simulations suggest greater uncertainty than reflected in the sentence I’ve quoted here. This range of uncertainty appears to extend from 270,000 years up to 400,000 years ago.

Again, this is an observation that confirms something already known from other work. The paper from Guy Jacobs and coworkers last year on Indonesian population diversity provided good evidence of deep Denisovan diversity. Many people in New Guinea today have a heritage including introgression from two different groups of Denisovans. Both of these Denisovan-like groups continued to exist until the last 40,000 years, it seems from the lengths of the introgressed haplotypes. Jacobs and coworkers denoted these Denisovan-like groups as D2 and D1. They estimated that the D2 group diverged from the population ancestral to both Denisova 3 and D1 around 360,000 years ago, and D1 diverged from the Denisova 3 population around 280,000 years ago. These findings pointed to very deep population diversity within “Denisovans”, more in fact that is present among the most diverse modern human groups.

These estimates of divergence dates are based on simplistic models of divergence with no subsequent gene flow. They are likely to be wrong. If these “Denisovan” populations behaved like modern human and Neanderthal groups, they probably shared some amount of gene flow at times after their divergence. That would make the “divergence date” estimates appear more recent than the real initial diversification of these populations.

It is not clear whether other Asian or island Southeast Asian populations may also have mixture from the “D2” population. The 2018 work from Browning and coworkers established that today’s Asian populations have Denisovan ancestry from at least two “waves” of introgression. One of those, accounting for around a third of the Denisovan-like ancestry in East Asian people today, looks to have been genetically similar to the Denisova 3 genome. The other wave was genetically quite divergent from this Denisova-3-like population. In the analysis by Browning and coworkers, they were able to find evidence for both waves in samples of living people originating from China, Japan, and Vietnam, including several ethnic groups in China. They even found a trace of the Denisova-3-like wave in Finland. But they found only the divergent wave in South Asian populations, and they did not identify either Denisovan wave in European populations other than Finland, or in samples with Native American ancestry. Browning and collaborators did not estimate a divergence date for this population, and Jacobs and coworkers did not establish whether this mainland Asian divergent wave was the same as either the D1 or D2 introgression source that they identified. So the identity of this divergent Denisova-like introgression wave at the moment is up in the air.

It is reasonable to ask whether the divergent Denisova-like wave that Browning and colleagues found in Asians might be the same as the Denisova-like ancestry that Skov and colleagues identify in Icelanders. It’s also reasonable to ask whether both of these represent the same source as the D2 population identified by Jacobs and coworkers.

I’m not convinced that they are the same, for reasons I’ll go into below. But it’s not a bad idea to start with the hypothesis that they might be the same, and think about how to test that. So I’ll propose that these signals all equate to the same divergent population, and that they originate from a Denisova-like population in South Asia.

In this hypothesis, most of the D2 component of ancestry in Sahulian populations actually reflects introgression from this divergent Denisovan group. The ancestors of today’s Sahulians would have encounted the D2 population as they transited South Asia. Later, they picked up ancestry from the different D1 population, which might come from a Wallacean or island Southeast Asian source.

Meanwhile, southwest Asian Neanderthals also had a small component of D2 ancestry. They got this from introgression or gene flow with the South Asian D2 population. That gene flow was not small, it had to be something like 6 to 8 percent of the genome of the southwest Asian Neanderthal population. The out-of-Africa wave of modern humans then picked up a small fraction of this D2 ancestry when they mixed with the southwest Asian Neanderthals. That component provides the measurable Denisovan ancestry in most of today’s people, including Icelanders. It also is present in New Guinea, but accounts for a much smaller amount of the D2 signature in this population.

This hypothesis leaves the timing of these events somewhat flexible. Today’s Sahulian groups are more divergent from other non-African populations than any of those populations are from each other, and they may have picked up their extra D2 ancestry anywhere along the road to Sahul. Jacobs and coworkers (2019) inferred the time of D2 mixture into New Guinea populations at 46,000 years ago, with an error interval going up to the time they estimate that these populations first differentiated from the stem out-of-Africa groups, around 51,000 years ago. These dates are contingent on a variety of assumptions in the article, and we cannot take them as “real” dates that we can test hypotheses with. They just give an indication of where this introgression is relative to the divergence of the New Guinea ancestral population from other populations today. Likewise, the models examined by Skov and coworkers looked at introgression among Neanderthal, Denisovan, and modern populations at or around 45,000 years ago. Their analyses provided some demonstration of how Denisovan introgression may have originated, but they could not differentiate the direct and indirect hypotheses from each other, much less provide real confidence intervals for the date of Denisovan introgression.

How could we test this hypothesis? What is needed is some further large samples of other populations to test whether the small component of Denisovan ancestry can really come from a single source. 27,000 people might be overkill for testing that, but more than a few thousand will be needed.

The observation by Browning and coworkers that South Asian peoples today have more detectable ancestry from the “divergent wave” of Denisovans than European or other groups is very interesting. Bergström and coworkers this year also found more evidence of Denisovan-like ancestry within their South Asian samples than in European samples. Meanwhile, those same samples showed more Neanderthal ancestry in European groups than in South Asian groups. This set of observations was not designed to examine the question of Denisovan ancestry via introgression from Neanderthals, so I don’t want to take the results too far out of context. But on the surface this doesn’t look like a simple Denisovan-via-Neanderthal-introgression hypothesis can work for all the “divergent wave” component. The ancestors of South Asian people seem likely to have mixed directly with divergent Denisovans in addition to any divergent Denisovan ancestry they may trace to Neanderthal introgression.

OK, this is all quite complicated, because none of these studies were really designed to answer this question, and most of them are underpowered to examine the difference between direct and indirect mixture scenarios. But someone will have to get into these details with larger sample soon, because the alternative is that there were possibly many mixtures with many different divergent Denisovan groups.

For me, disproving the hypothesis that a single D2 population can account for all this Denisovan ancestry would be a welcome conclusion. After all, what reason do we have to assume that nature was parsimonious with its Denisovans? Much of what we know makes me expect to find more diversity among past peoples, not less. The divergence of the Denisovans from Neanderthals was definitely before 430,000 years ago, constrained by the fact that the Sima de los Huesos genomic samples are already on the Neanderthal population branch. According to estimates by Alan Rogers and coworkers, the Denisovan origin was likely soon after the stem Neanderthal-Denisovan common ancestors parted ways from sub-Saharan Africans, possibly close to 700,000 years ago (see my 2017 post, “How long ago did Neandertals and Denisovans part ways?”).

Four populations that only began diverging after 400,000 years ago would seem to be a paltry sampling of the Denisovan diaspora. If there weren’t other Denisovans, we’ll need to explain why.