A sad end for the Journal of Human Evolution

A joint statement announces the resignation of the entire editorial board, while disclosing for the first time the use of AI in article production.

Note: Elsevier has released a statement about this editorial board resignation, in which the company states that the editors' claims about AI are inaccurate, and AI is not used in Elsevier's production process. I have posted an update at the bottom of this post.

This week the editorial board of the Journal of Human Evolution issued a press release announcing their joint resignation, leaving the journal without any evident future. The journal has been a property of the publishing conglomerate Elsevier since the company acquired Academic Press more than twenty years ago.

In their statement, the editors explained several conflicts with Elsevier that led them to their decision. An important issue seems to have been the level of compensation for the joint editors-in-chief. They also discuss Elsevier’s persistent demands to reduce the number of associate editors, failure to give new editorial board members access to the system and the exclusionary cost of open access options for authors.

The most explosive revelation is in a footnote to the announcement: Elsevier has been using AI tools in its production process that—according to the statement—consistently introduce errors that require “extensive author and editor oversight” to correct.

The editors shared the press release on several social media sites, and Retraction Watch has provided a copy of the statement as PDF.

Many researchers have published valuable work in the Journal of Human Evolution. Over the years I’ve been an author of seventeen articles in the journal, the first back in the Academic Press days, adding up to hundreds of pages of research in the journal’s pages and in supplementary online materials. It's a place where I’ve sent some fundamental work, and the journal has been important for many of my coauthors to build their academic records. I don't have any count of the number of manuscripts the journal has asked me to review, but I'm pretty sure I haven't ever turned one down.

As an author I was shocked to read the editors’ statement on how AI has affected their process. The press release says that editors were not told in advance about the use of AI when it was introduced in 2023. They write that the formatting of basic scientific terms, such as names of epochs, countries, and species, were changed. As they write:

“This was highly embarrassing for the journal and resolution took six months and was achieved only through the persistent efforts of the editors. AI processing continues to be used and regularly reformats submitted manuscripts to change meaning and formatting and require extensive author and editor oversight during proof stage.”—Editors of Journal of Human Evolution

I’ve published four articles in the journal during the last two years, including one in press now, and if there was any notice to my coauthors or me about an AI production process, I don’t remember it.

The Journal of Human Evolution Guide for Authors says nothing about AI in the editorial process. But it does extensively address the use of AI by authors. The journal forbids the use of “generative AI or AI-assisted tools” in images or figures. The journal allows the use of AI-assisted technologies in writing and editing, but clearly requires authors to declare such uses of AI in their work.

“The use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in scientific writing must be declared by adding a statement at the end of the manuscript when the paper is first submitted.”—Elsevier Guide for Authors

It seems to me that if the journal followed its own policy, all published articles since 2023 would include a disclosure that AI-assisted technologies were used in the final product!

I can understand the editors’ frustration from so much wasted effort and embarrassment. But the real lapse is a more basic matter of ethics. Authors should be informed at the time of submission how AI will be used in their work. I fully support the decision of the editors to protest and ultimately resign, and this issue alone would be enough. In my opinion it was wrong for Elsevier not to disclose this to potential authors. I would have submitted elsewhere if I was aware that AI would potentially be altering the meaning of the articles.

Some reading this might wonder, what's the big deal? These changes in scientific publishing are to some degree inevitable. The tedious transcription of manuscripts into formatted journal pages is one task that should absolutely be the easiest for machine approaches. Heck, it's hard for me to believe that a publisher like Elsevier would rely on such slipshod automation when other publishers already have much better capacity.

But not all uses of machine learning are equal.

In my opinion it's good for scientists to use AI to amplify and enhance their research, and for publishers to use AI to make work easier to disseminate. There is no question we are moving toward a future where machine approaches will be applied more and more, not only to the production of scientific work but also to its evaluation. I don’t think this is a dystopian future. There is a lot to gain from building machine learning based upon the best current scientific findings. I expect we will find ways to use these approaches to single out the weak points in our research and to bring fields together toward synthetic insights.

But it’s bad for anyone to use AI to reduce or replace the scientific input and oversight of people in research—whether that input comes from researchers, editors, reviewers, or readers. It’s stupid for a company to use AI to divert experts’ effort into redundant rounds of proofreading, or to make disseminating scientific work more difficult.

In this case, Elsevier may have been aiming for good but instead hit the exacta of bad and stupid. It’s especially galling that they demand transparency from authors but do not provide transparency about their own processes.

In light of what the editors have shared about the extent of AI-generated errors in the JHE production process, it would be a very good idea for authors of recent articles to make sure that they have posted a preprint somewhere, so that their original pre-AI version will be available for readers. As the editors lose access, corrections to published articles may become difficult or impossible.

I’m sad to see the Journal of Human Evolution come to this end. Maybe Elsevier will try to keep it alive by recruiting a new editorial board, but I would not expect many takers.

But I am much more hopeful now for the future of research in this field. As science moves into a new future of publishing, anthropologists and archaeologists have an enormous opportunity to broaden participation and impact by supporting more open approaches in publishing and dissemination of research.

Update

(Last updated 2025-01-10): Retraction Watch has received and posted parts of a statement from Elsevier about the editorial board resignations from Journal of Human Evolution. The post emphasizes the portion of Elsevier's statement that reacts to the claims about AI in their production process: “Elsevier denies AI use in response to evolution journal board resignations”. I quote the relevant passage here:

We do want to address an important inaccuracy in the statement issued by the outgoing editors, specifically the incorrect linking of a formatting glitch to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in our production processes. We do not use AI in our production processes. The journal trialled a production workflow that inadvertently introduced the formatting errors to which the editors refer. We had already acted on their feedback and reverted to the journal’s previous workflow earlier in 2024.

This seems to me to be a significant statement, and if it's accurate, it alters my view of the story. The editors and entire board are respected scientists in their respective fields, and for them to totally misunderstand the nature of production of articles in the journal seems incredible. Did someone at Elsevier tell the editors that AI was being used in this production workflow? Or did the editors release the public statement with such a significant error?

Science has also reported on the story, indicating that both resigning editors and one former editor all confirm that Elsevier told them in 2023 that implementation of AI had caused errors in the production workflow. In my view this places the responsibility for any miscommunication within Elsevier.

As I wrote above, one of the biggest ethical problems is that the editors didn't inform authors that AI was being used, as soon as they knew. As an author, I expect the journal's editors to be candid about their processes.

This week, Springer Nature has announced two different initiatives to introduce AI into their editorial process for journals. The use of automated processes using machine learning in the evaluation of scientific research is clearly on the agenda for many scientific journals.

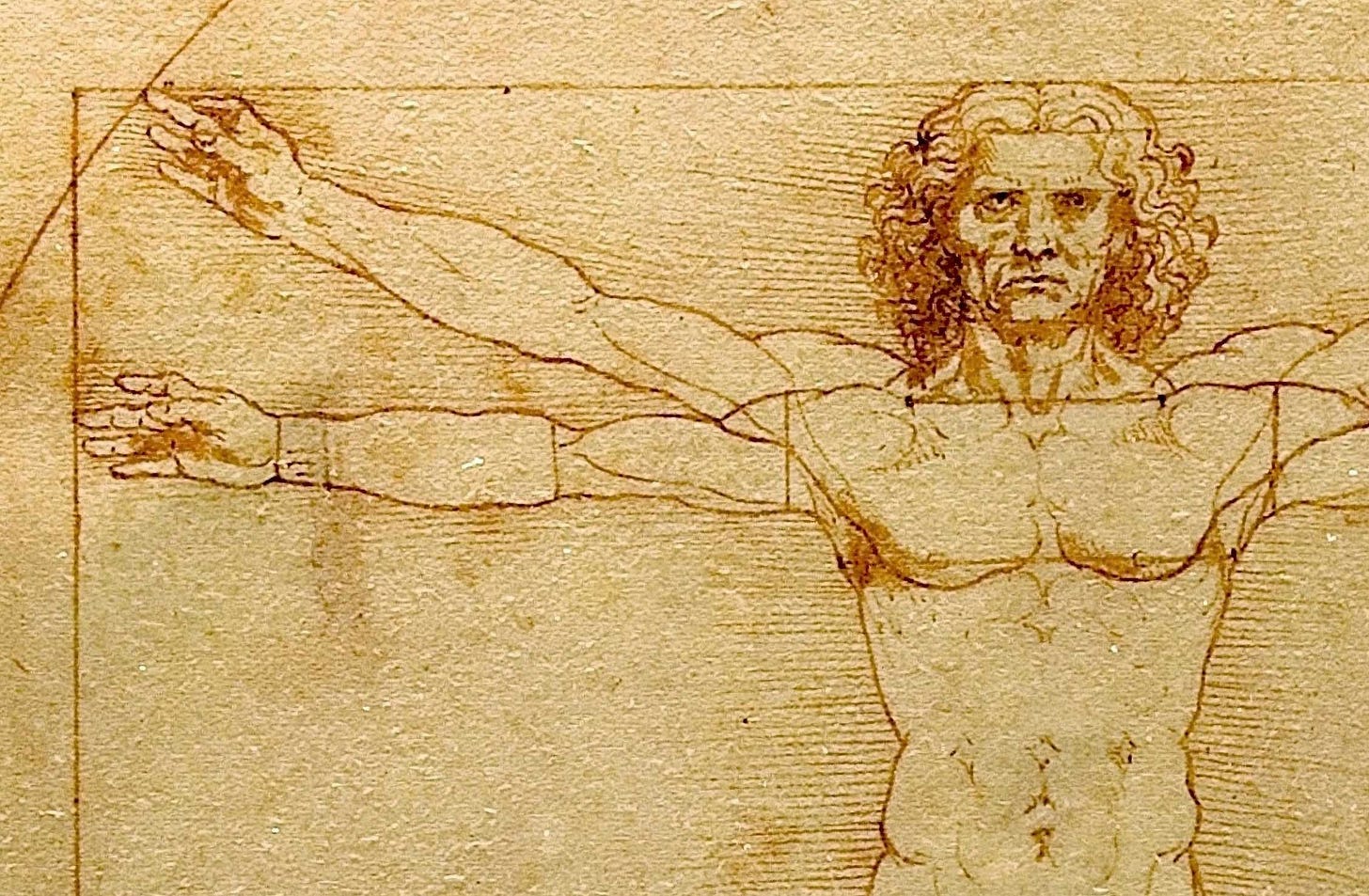

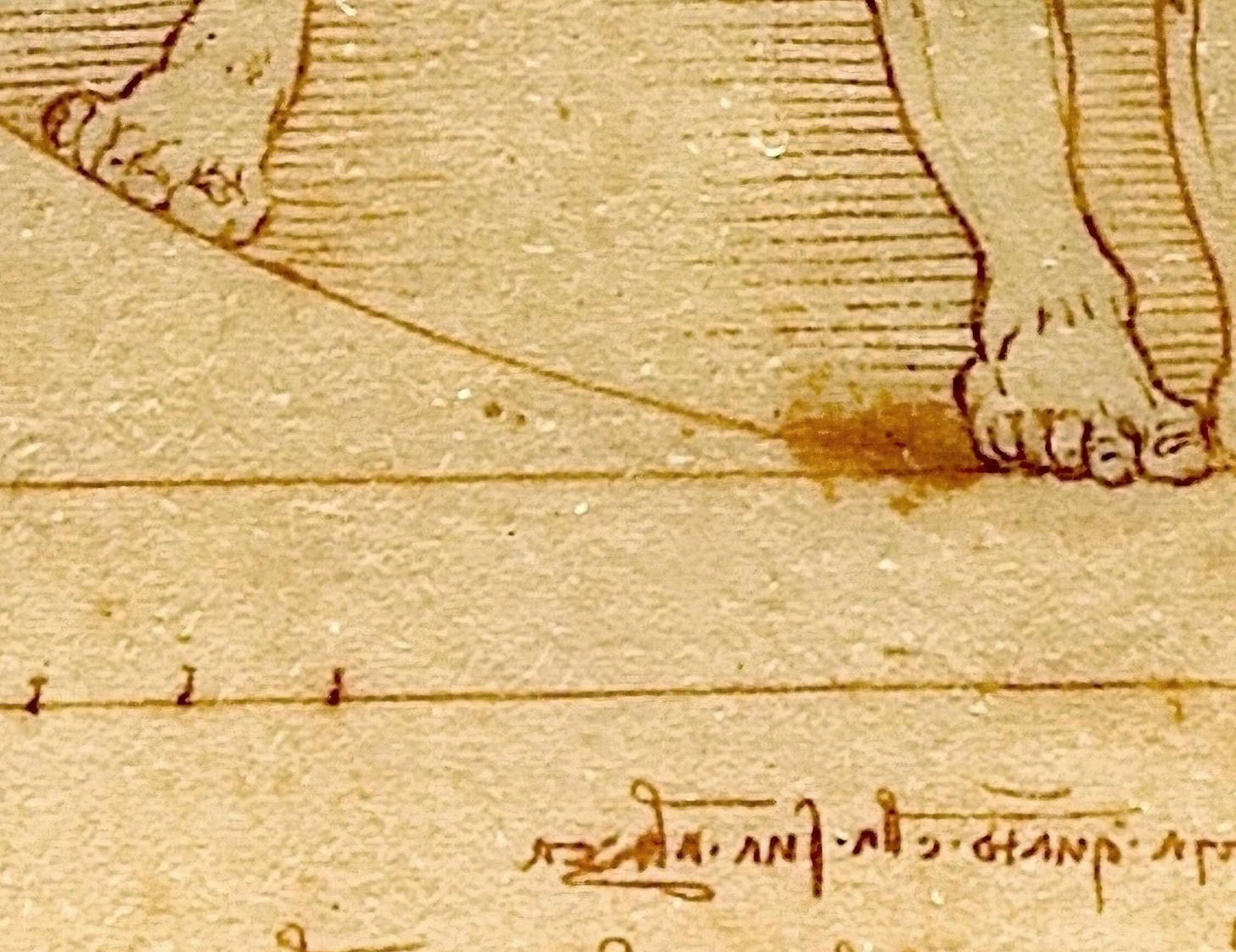

Notes: The images in the post pay tribute to the Academic Press days when the cover of every issue of the Journal of Human Evolution had a simplified Vitruvian Man.

The mass resignation of editors raises other issues that I haven’t addressed in this post. I have already seen a number of my colleagues around the world commenting on the challenges in publishing new research with the loss of the Journal of Human Evolution. I care deeply about making scientific work available to everyone regardless of their geographic location or connections to institutions. I think we stand at a moment of opportunity, and will comment more on this in a later post.

March 6, 2025: Elsevier has now published a “Publisher Note” with some points responding to the resignation of the editorial board and discussing aspects of production of articles going forward.