A look at the Maba hominin skull

Found in 1958, the skull is one of a handful of fossil hominins from southern China that may be connected with the Denisovans.

On the shelf in my office I have a 3D print of the Maba 1 hominin skull. What is preserved from this individual is not that much: only part of the right parietal and temporal, the adjoining part of the occipital bone, a bit more than half the frontal bone, and pieces of the right zygomatic and interorbital pillar. Sometime after the individual's death the brow was chewed by rodents, exposing a large frontal sinus.

Overall, it leaves a striking impression. The thick fragments of vault have a visual heft, even when printed in plastic.

The pieces of this skull were found in a cave in 1958 by farmers who were digging guano for fertilizer. The cave is within one of two abrupt hills known as the Lion Rocks (shizishan) near the Maba village, which is just south of Shaoguan in Guangdong province. Today these hills are part of a park including a museum that commemorates the find. Large apartment blocks have sprung up all around.

For years the Maba skull was one of the few hominin discoveries from southern China. How it might fit together with other fossils was not very clear. The most famous fossil discoveries from China were early Middle Pleistocene in age, including the Homo erectus series from Zhoukoudian, near Beijing.

During the 1980s, early uranium-series dating of a flowstone suggested that the skull dates to the last interglacial, roughly 130,000 years ago. At that age, the skull would be contemporary with the Neandertal fossils from Krapina, Croatia, and the remains of early modern people from Skhūl Cave, Israel. The anatomy of Maba 1 echoes neither of these faraway groups. Some scientists thought of the Maba skull as representing the hominin population of China that lived at the same time that Neandertals lived much further to the west.

Scientific ideas about the skull's antiquity changed with recent work by Guanjun Shen and collaborators in 2014. This team carried out survey of the cave system to try to better understand the overall chronology, and dated a capping flowstone that they suggested was a minimum for deposition of materials in the area where the skull had been found. The time represented by this flowstone, 230 ± 5 ka, is roughly double what scientists previously considered as the age of Maba 1. Still, there is uncertainty. The skull was not excavated under controlled circumstances and its relationship to sediment deposits will always remain uncertain.

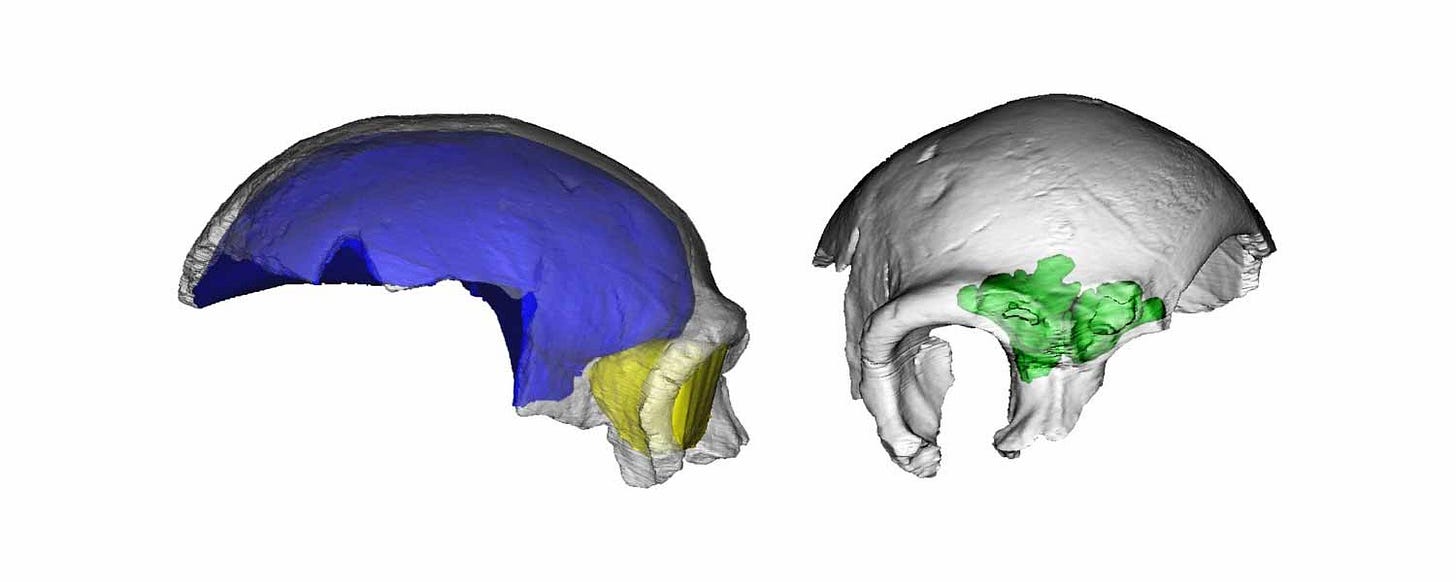

An earlier date does little to change the evolutionary interpretation of the skull. It differs from Homo erectus in its higher forehead, slightly thinner vault bones, and larger brain size. Yet its vault and brow are thicker than in modern people. Examination of the endocranial surface by Emiliano Bruner and Xiujie Wu revealed a frontal lobe anatomy similar to archaic humans. With this in-between form, it's been called “archaic Homo sapiens”, and even Homo heidelbergensis.

In today's way of thinking, Maba 1 is among many fossil individuals from China that might someday be connected with the Denisovans. But unlike many of the Middle Pleistocene fossils from northern and central China, no scientists have yet connected Maba 1 with groups like Homo longi or the Julurens.

No archaeological materials were found with the skull, neither at the time of its discovery nor since. Later exploration of the system by archaeologists in 1960 unearthed part of a human jaw, and excavations in 1984 recovered several teeth. None can be associated with the Maba 1 skull. Recent study of these other human remains by Dongfang Xiao and coworkers showed the jaw and isolated teeth likely came from much later modern humans.

Though the surviving fragments are limited in the information they can provide, it is still possible to say something about the individual's life. The individual was adult at the time of death. Most anthropologists have considered Maba 1 to have been a male individual, based on the thickness and the brow and general size and thickness of vault bones, but this is not certain.

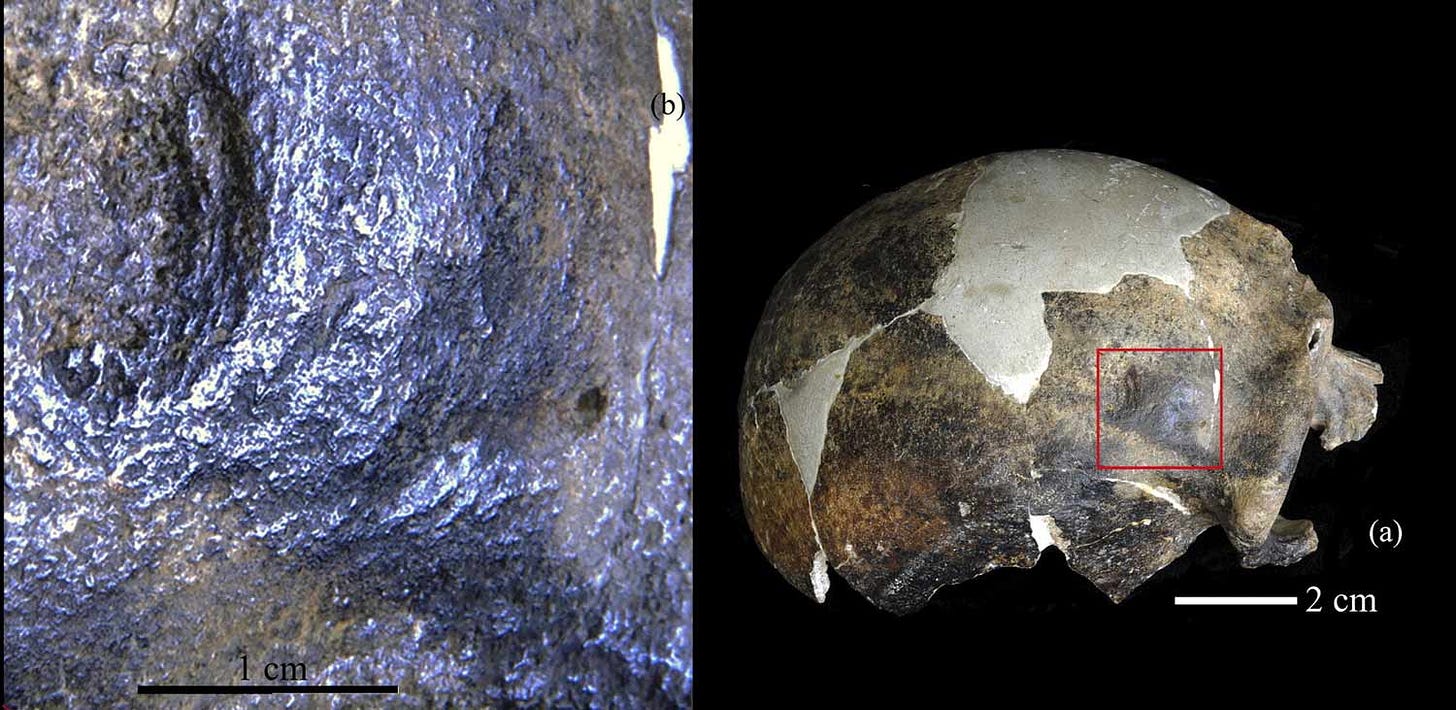

The left side of the frontal bone reveals what may have been a startling moment of violence during the individual's life. On the bone's external surface a semicircular depression, nearly a centimeter in diameter, is lined with concentric ridges of healed bone. On the internal surface of the frontal, just opposite the depression, is a raised bump. Examined with CT scans by Xiujie Wu and coworkers in 2011, the structure also disrupts the spongy structure within the bone, known as diploë.

This combination of evidence shows that the individual received a severe blow to the head, sufficient to generate not only external fracturing but also a closed-head injury within the skull. While it's not possible to be sure what caused this injury, Wu and collaborators noted that similar injuries often result from interpersonal violence. Whatever happened, the injury did not lead immediately to death. The extensive healing shows that the individual did recover, after a healing process that would have taken at least months and possibly longer.

The Middle Pleistocene fossils of China are giving rise to many new insights. As researchers apply new methods and approaches, they often look at old discoveries with fresh eyes. The Maba skull will always be limited in what it can tell us about the big picture of hominin diversity in this part of the world. Still, it may yet have more to say.

Notes: The work by Shen and collaborators (2014) provides great context about the discovery and the overall layout of the cave system in the Lion Rock. Bae (2010) provides a review of the overall Middle Pleistocene record of China, with description of Maba 1, and Bae and coworkers (2023) review the taxonomic situation. My earlier post on the Julurens gives an overview of new work in northern and central China, and connections with Denisovans.

References

Bae, C. J. (2010). The late Middle Pleistocene hominin fossil record of eastern Asia: Synthesis and review. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 143(S51), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21442

Bae, C. J., Liu, W., Wu, X., Zhang, Y., & Ni, X. (2023). “Dragon man” prompts rethinking of Middle Pleistocene hominin systematics in Asia. The Innovation, 4(6), 100527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100527

Shen, G., Tu, H., Xiao, D., Qiu, L., Feng, Y., & Zhao, J. (2014). Age of Maba hominin site in southern China: Evidence from U-series dating of Southern Branch Cave. Quaternary Geochronology, 23, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2014.06.004

Wu, X., & Bruner, E. (2016). The endocranial anatomy of Maba 1. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 160(4), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22974

Wu, X.-J., Schepartz, L. A., Liu, W., & Trinkaus, E. (2011). Antemortem trauma and survival in the late Middle Pleistocene human cranium from Maba, South China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(49), 19558–19562. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117113108

Xiao, D., Bae, C. J., Shen, G., Delson, E., Jin, J. J. H., Webb, N. M., & Qiu, L. (2014). Metric and geometric morphometric analysis of new hominin fossils from Maba (Guangdong, China). Journal of Human Evolution, 74, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.04.003