A look at the fossil skull from Steinheim

The skull provides some of the best evidence for the ancestral population of Neandertals, and had a tumultuous history in the decades after its discovery.

The small town of Steinheim an der Murr is around 20 km north of Stuttgart, Germany. On July 21, 1933, Karl Sigrist, Jr., was working in the gravel pit his father owned near the town, when he uncovered a skull. At the time of its discovery it was one of the very few pieces of evidence of human evolution in Europe before the Neandertals and it remains highly significant today.

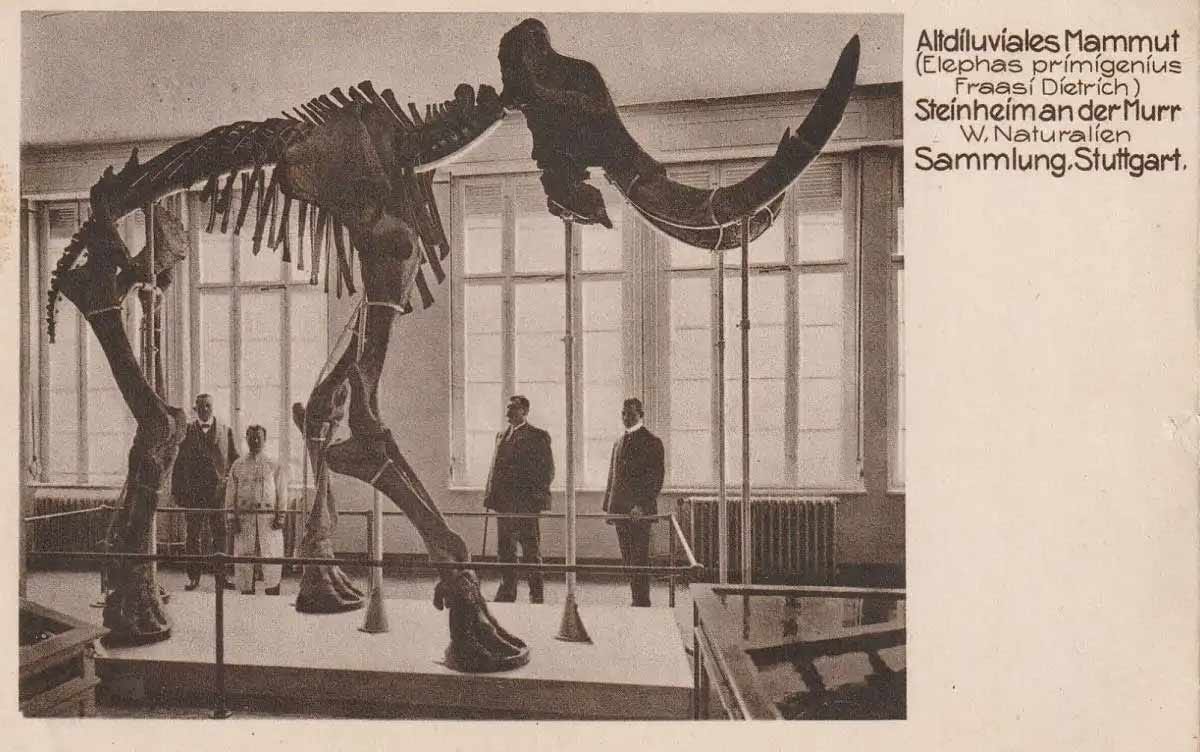

When the skull was found, fossil discoveries from the Steinheim gravel pits had been well known by paleontologists for more than two decades—especially after the discovery of a woolly mammoth skeleton in 1910. The owners of gravel pits in the area, including Karl Sigrist, Sr., and neighbors Bauer and Sammet, had a standing arrangement to call the curators of the Stuttgart Natural History collection when any interesting fossils were unearthed in the pits.

Sigrist reached out immediately to Fritz Berckhemer, chief curator at Stuttgart, who hopped that day on the railway to Steinheim. The skull was left in place until Berckhemer and the chief preparator, Max Böck, could record its surroundings and assess its condition. They made a thorough search for additional bones or stone artifacts but found none.

Berckhemer's son Hans—who later became a geophysicist—was age 7 when he accompanied his father to the site that day. He recounted the story in an event held for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Steinheim discovery in 2008:

“My father received a phone call from Mr Sigrist on the morning of July 24th. Mr Hölder, who was a high school student in Stuttgart at the time and witnessed the phone call, later a professor of paleontology in Tübingen and Münster, still remembers the words ‘an ape was looking out of the sand wall’.… My father saw immediately that it was a human skull and that everything had to be done to remove it intact from the surface. But that could only be done together with the chief preparator Böck the next day after covering it with a cloth soaked in plaster and carefully separating it from the embedding.”

The recovery and preparation of the skull were thus highly professional for the time. The skull was within a thick layer of Murr gravel from which teeth and bones of mammoth, rhinoceros, horses, and other animals had been found. These were older than the animals in Neandertal sites, and were thought to come from before the Riss glaciation.

Today this general idea about the skull's age is still accepted. The Murr gravels represent interglacial periods, with overlying loess deposits. Correlations of the faunal remains with those from other European fossil sites have suggested that the most likely timing of the deposit is within Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 9 or MIS 11, the latter correlated with the Holsteinian interglacial. This would place the skull sometime between 450,000 and 300,000 years ago. No radiometric date has yet been derived for the skull itself or other fossil material from the site.

Berckhemer published the first description of the skull and its context in 1933. He recognized the strong browridge and elongated skull shape—the aspects that had led Sigrist to describe it as an ape. These suggested similarity with the Neandertals. Yet Berckhemer also pointed to some features that seemed more reminiscent of living people, especially the relation of the nose to the cheekbone and some aspects of the teeth. He concluded that the Steinheim individual had been on “a separate line of development” from Neandertals, one closer to modern humans.

From the 1930s onward, the growing fossil record from other places and times has changed perspectives on the Steinheim skull. Its more modern aspects were soon understood to be shared with fossils like the Homo erectus series from Zhoukoudian, China, which were just coming to light as Berckhemer wrote. Most anthropologists adopted the perspective that the Neandertal features reflected the skull's identity within a population that evolved into Neandertals.

For Berckhemer, the dream began to fade three years after the discovery. He published again on the skull in 1936, coining the name Homo steinheimensis, and arranged for the publication of a more complete monograph-length description. But scientists with Nazi connections were growing in power and influence. Within the field of anthropology one of these scientists was Hans Weinert, who had become Director of the Anthropological Institute of the University of Kiel. Weinert published a 50-page article describing the Steinheim skull and his own interpretation of its place in evolution.

Berckhemer was devastated. While he would publish a retort to Weinert's study, he held back his own longer work and did not complete it. His son described what happened next:

“The find was not to fall into the wrong hands again. How could this be prevented? By bringing the precious skull home – and where was it safest? In the bedroom. To the right of my father lay my mother and to the left Miss steinheimensis, naturally well protected in the skull case, which still exists and stands here as a historical document.”—Hans Berckhemer

With Germany's descent into war, the fossil not only had to be protected from the eyes of other scientists but also from air raids, which increased in pace. Eventually, Berckhemer consigned it to the Kochendorf salt mine, site of an infamous underground complex intended as a factory for slave labor from concentration camps. There, locked underground with priceless art looted from across Europe, the Allied armies found it.

After the war, according to Hans Berckhemer, the skull went to his uncle, a director at the Landeszentralbank, where it stayed until finally returning to the Naturkundemuseum Stuttgart where it resides today.

Our picture of the relationships of Middle Pleistocene Europeans has shifted a lot from the 1950s, when researchers categorized the Steinheim skull as one of several “pre-Neandertal” fossils. There is no DNA from the Steinheim individual. But DNA from another site of similar age, Sima de los Huesos, Spain, has revealed a Middle Pleistocene population different from their later Neandertal descendants in ways that reflect recurrent genetic exchanges from Africa. Neandertal ancestors began to separate from African populations by around 700,000 years ago. But they reconnected from time to time. Sometime between 350,000 and 200,000 years ago those exchanges brought African mtDNA and Y chromosomes into ancestral Neandertals, together with as much as 10% of the whole genome.

The idea would have appealed to Franz Weidenreich, who described the Zhoukoudian Homo erectus sample and pondered their relationship to Steinheim and other European fossils. Weidenreich argued that all these should be categorized within our own species, Homo sapiens.

Today there is no consensus on what to call the Steinheim skull. The idea that this and other Middle Pleistocene fossils should be attributed to Homo heidelbergensis is falling away, as their Neandertal connections have become more and more clear. Some scientists prefer to attribute Steinheim to Homo neanderthalensis. Personally, I'm inclined toward Weidenreich's view that the anatomical differences are not enough to separate them from other populations ancestral to humans.

In this century, researchers have added new detail to the anatomical understanding of the Steinheim individual. The skull was one of the earliest fossil hominins to be the subject of CT scanning, enabling researchers to virtually remove matrix and study the shape and size of the paranasal sinuses. Recently, Costantino Buzi and coworkers attempted to correct for some of the postmortem deformation of the skull, helping to show that its cranial vault and face were a bit more like Neandertals than it might have appeared.

The scanning also brought to light an unexpected finding. The right parietal bone is thinned by an oval depression on its internal surface. This area, around 3 cm in diameter, resulted from a tumor within the membranes surrounding the brain, known as a meningioma. As examined by Alfred Czarnetzki and collaborators, the diagnosis of meningioma was supported not only by the size and shape of this thinned area but also by an enlarged trace of the middle meningeal artery, found in some 70% of cases today.

“In view of the demanding Pleistocene living conditions, this tumour size in conjunction with the small Steinheim cerebrum of only 1100-1200 mL (modern brain: 1300–1800 mL), might have caused continual headache, severe hemiparesis, and finally death.”—Alfred Czarnetzki and coworkers

How the skull came to settle after death in the bed of the ancient Murr is not known. Berckhemer and later Karl Dietrich Adam speculated that the breakage was due to violence or cannibalism, which had been suggested for the Zhoukoudian Homo erectus fossils also. But no traces show the skull was damaged by either stone tools or predators. With its friable condition it may simply have been broken from rolling in the riverbed.

Many anthropologists over the years have favored the idea that the skull represents a female individual. This was basis of the recent reconstruction of the individual's appearance by Élisabeth Daynès. Yet the size of the Steinheim skull is near the middle of the range of size of Middle Pleistocene fossils, and without more context about the variation in its local population, it's not possible to be sure. Sampling of the teeth for protein evidence has become one avenue of information about the sex of ancient remains, and in the future sampling of the Steinheim skull's teeth may be possible with minimal damage.

Collecting data on the stable isotope composition of the teeth might also shed light on the diet of this individual. The Neandertals of the last glacial period in Europe relied very strongly on meat. Gathered plant foods were part of their diet but not a large fraction of what they consumed. Earlier European populations, during interglacial periods, may have had more dietary options.

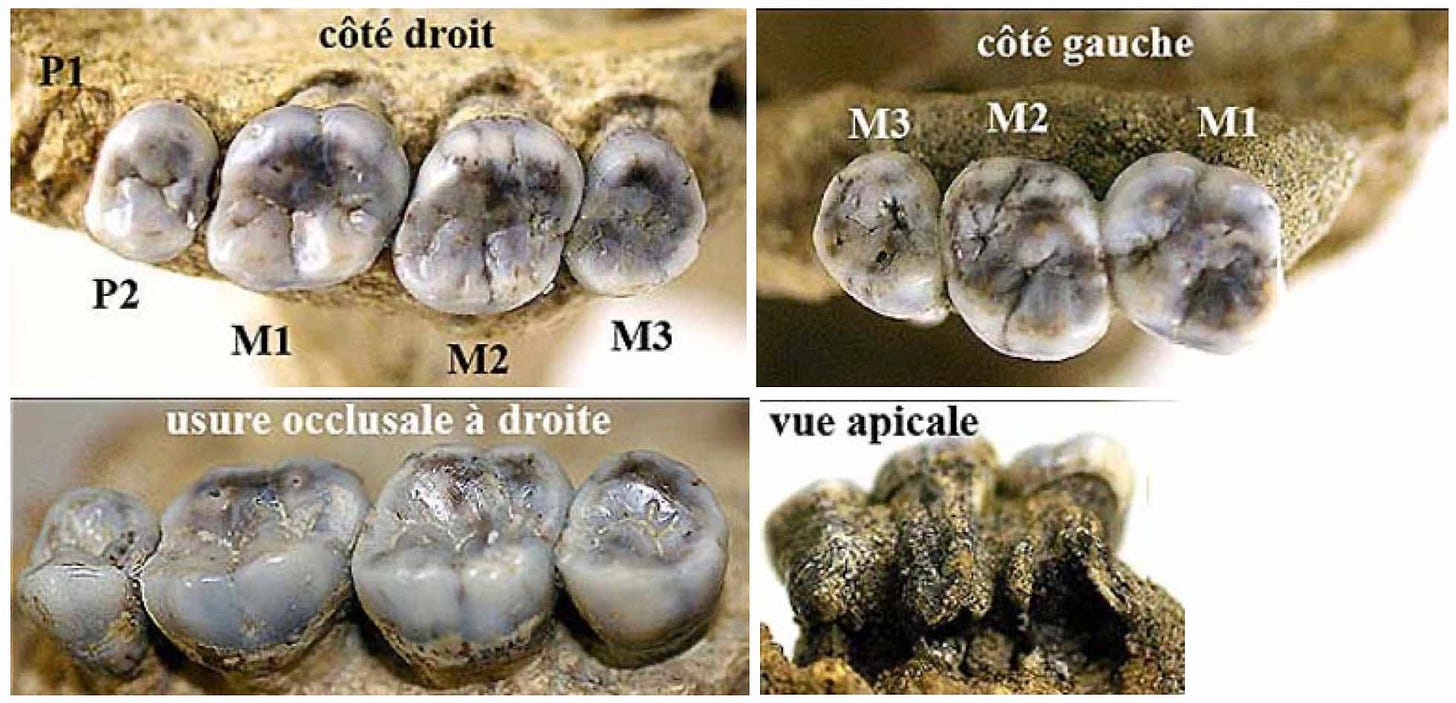

The kill site and wooden artifacts from Schöningen, Germany, illustrate that the hominins of central Europe in the days before Neandertals did rely on cooperative hunting of large mammals. But there are signs that their diets were more extensive. Sireen El Zaatari in a 2007 study was able to examine the microscopic wear on one of the molars of the Steinheim skull, together with more than 50 other Neandertals and earlier European fossils. Steinheim fits together with other fossils inferred to have lived in more forested environments, comparable to prehistoric hunter-gatherers in the Mediterranean region, where people ate a wide variety of gathered and hunted foods. The microwear was quite different in higher-latitude hunters who ate mostly meat, who looked more like the glacial-era Neandertals.

Every fossil human relative opens windows into ancient lives. We cannot always predict how much they may tell us about the lifetime of an individual, or the collective lives of an entire population. In the case of the Steinheim skull, new discoveries have followed whenever scientists have taken another close look at the fossil. With so many remaining unknowns, this ancient individual doubtless has much left to teach us.

Notes: The town of Steinheim has a small museum, the Urmensch-Museum, which has a very informative website with many images, including a reconstruction by Elisabeth Daynès of the individual.

The remembrance of Hans Berckhemer about his father's work with the Steinheim fossil is one of several sources that review the history of the find, and I've included translations of quotes from it because they are so evocative of the story. The cited chapter from Karl Dietrich Adam and other works by him and Fritz Berckhemer himself give good accounts of the find.

References

Adam, K. D. (1985). The chronological and systematic position of the Steinheim skull. In Delson, E., Ancestors: The Hard Evidence (A. R. Liss, New York), 272-276.

van Asperen, E. N. (2013). Position of the Steinheim interglacial sequence within the marine oxygen isotope record based on mammal biostratigraphy. Quaternary International, 292, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.10.045

Berckhemer, F. (1933). Ein Menschen-Schädel aus den diluvialen Schottern von Steinheim a. D. Murr. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 10(4), 318–321.

Berckhemer, H. (2008). 75 Jahre Homo steinheimensis: Erinnerungen von Prof. Dr. Hans Berckhemer (Frankfurt), korrespondierendes Mitglied der Gesellschaft für Naturkunde. Jahreshefte der Gesellschaft für Naturkunde in Württemberg, 164, 197-199.

Buzi, C., Profico, A., Di Vincenzo, F., Harvati, K., Melchionna, M., Raia, P., & Manzi, G. (2021). Retrodeformation of the Steinheim Cranium: Insights into the Evolution of Neanderthals. Symmetry, 13(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13091611

Czarnetzki, A., Schwaderer, E., & Pusch, C. M. (2003). Fossil record of meningioma. The Lancet, 362(9381), 408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14044-5

El Zaatari, Sireen. (2007). Ecogeographic variation in Neandertal dietary habits: Evidence from microwear texture analysis [PhD, State University of New York at Stony Brook].

Granat, J., & Peyre, E. (2009). L’énigme odontologique du crâne de Steinheim 280 ka—Allemagne. Actes SFHAD, 13, 14.

Lauer, T., & Weiss, M. (2018). Timing of the Saalian- and Elsterian glacial cycles and the implications for Middle – Pleistocene hominin presence in central Europe. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 5111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23541-w

Prossinger, H., Seidler, H., Wicke, L., Weaver, D., Recheis, W., Stringer, C., & Müller, G. B. (2003). Electronic removal of encrustations inside the Steinheim cranium reveals paranasal sinus features and deformations, and provides a revised endocranial volume estimate. The Anatomical Record Part B: The New Anatomist, 273B(1), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.b.10022

Weinert, H. (1936). Der Urmenschenschädel von Steinheim. Zeitschrift Für Morphologie Und Anthropologie, 35(3), 463–518.