Darwin witnessing the plagues of European colonization

He described the destruction of Indigenous peoples as the result of a “mysterious agency” but saw the evidence of infectious disease firsthand.

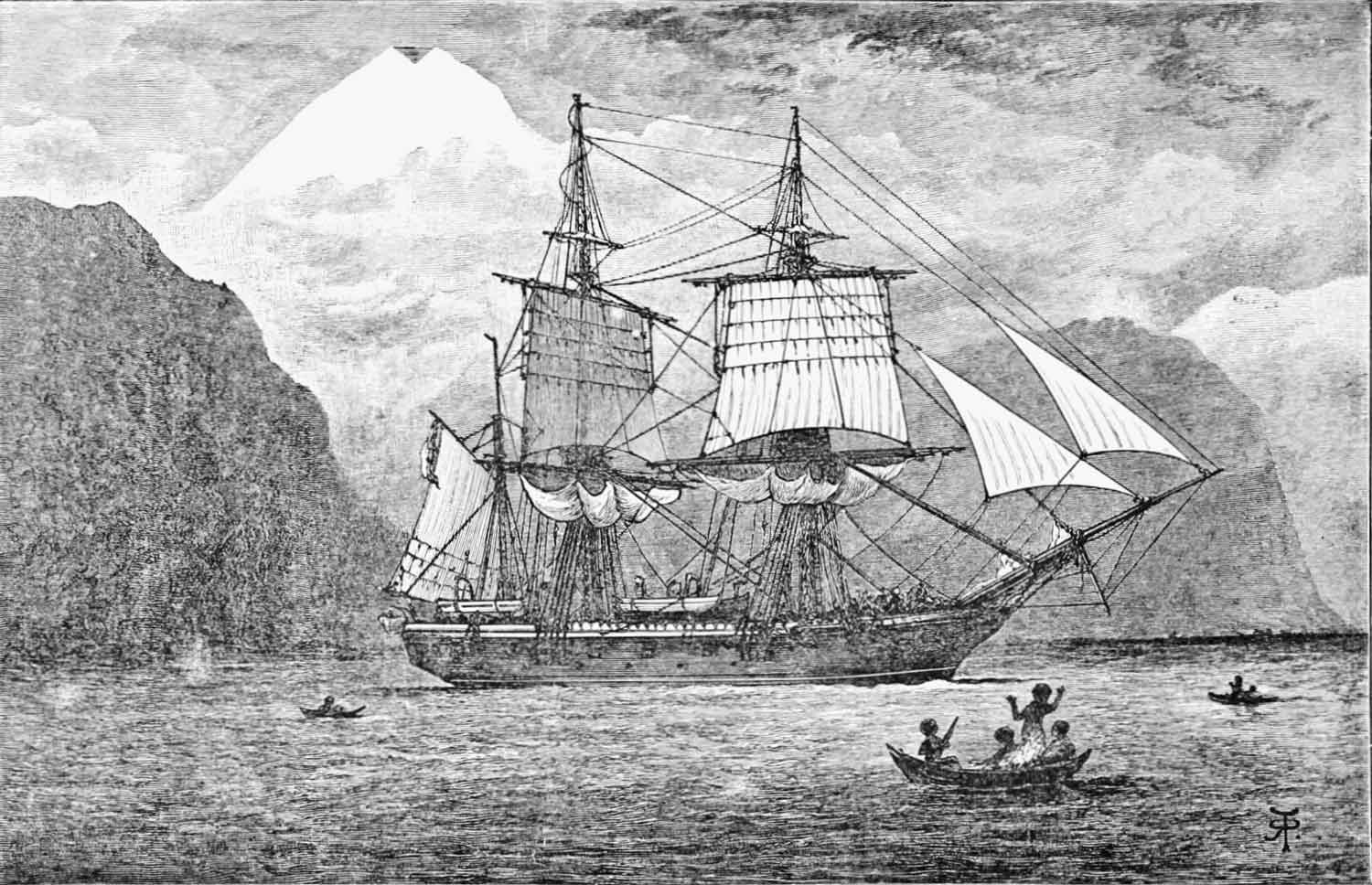

Alfred Crosby gives a short quote from chapter 19 of Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle, and I found it interesting enough to look for the full context. Voyage is online free at several places. Because it's online I don't have ready page numbers for the quotes below, they are all from chapter 19.

The passage is part of Darwin's description of Australia, which he finds “in all respects there was a close resemblance to England: perhaps the alehouses here were more numerous.”

Then he takes up the subject of the Aboriginal people:

The number of aborigines is rapidly decreasing. In my whole ride, with the exception of some boys brought up by Englishmen, I saw only one other party. This decrease, no doubt, must be partly owing to the introduction of spirits, to European diseases (even the milder ones of which, such as the measles, [1] prove very destructive), and to the gradual extinction of the wild animals. It is said that numbers of their children invariably perish in very early infancy from the effects of their wandering life; and as the difficulty of procuring food increases, so must their wandering habits increase; and hence the population, without any apparent deaths from famine, is repressed in a manner extremely sudden compared to what happens in civilized countries, where the father, though in adding to his labour he may injure himself, does not destroy his offspring.

Besides the several evident causes of destruction, there appears to be some more mysterious agency generally at work. Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal. We may look to the wide extent of the Americas, Polynesia, the Cape of Good Hope, and Australia, and we find the same result.

The last passage (from “Wherever” to “result”) was quoted by Crosby. I think the preceding paragraph gives important context to Darwin's thinking on the matter; he had the main elements (which would probably have been common knowledge), although his attribution of juvenile mortality to a “wandering life” probably would be more correctly directed toward disease as well.

But that doesn't give the after context, either. Here's what follows in the same paragraph:

Nor is it the white man alone that thus acts the destroyer; the Polynesian of Malay extraction has in parts of the East Indian archipelago, thus driven before him the dark-coloured native. The varieties of man seem to act on each other in the same way as different species of animals—the stronger always extirpating the weaker. It was melancholy at New Zealand to hear the fine energetic natives saying that they knew the land was doomed to pass from their children. Every one has heard of the inexplicable reduction of the population in the beautiful and healthy island of Tahiti since the date of Captain Cook's voyages: although in that case we might have expected that it would have been increased; for infanticide, which formerly prevailed to so extraordinary a degree, has ceased; profligacy has greatly diminished, and the murderous wars become less frequent.

He finishes this section with some discussion of the mechanism of disease spreading by ship—even when no symptoms were found among the crew. This idea, which Darwin attributes to Williams' Narrative of Missionary Enterprise, has become important to explain certain New World epidemics as well as those in Polynesia.

This is a valuable quote for Crosby to have used because it shows that many educated people were aware that disease had decimated (and was still decimating) indigenous peoples, even as historians ignored disease as a factor in their narratives of New World conquest and colonization.

But then Darwin went further. He interpreted disease susceptibility in aboriginal peoples not as mere happenstance, but a symptom of European superiority.

The final line of Darwin's chapter gives more idea of the tone of the book and his account of Australia.

Farewell, Australia! you are a rising child, and doubtless some day will reign a great princess in the South: but you are too great and ambitious for affection, yet not great enough for respect. I leave your shores without sorrow or regret.

A second Darwin passage quoted by Crosby (1994) is from the Descent of Man, where Darwin wrote once more about the population growth in European colonies:

The remarkable success of the English as colonists over other European nations, which is well illustrated by comparing the progress of the Canadians of English and French extraction, has been ascribed to their "daring and persistent energy;" but who can say how the English gained their energy. There is apparently much truth in the belief that the wonderful progress of the United States, as well as the character of the people, are the results of natural selection; the more energetic, restless, and courageous men from all parts of Europe having emigrated during the last ten or twelve generations to that great country, and having there succeeded best.27 Looking to the distant future, I do not think that the Rev. Mr. Zincke takes an exaggerated view when he says:28 “All other series of events — as that which resulted in the culture of mind in Greece, and that which resulted in the empire of Rome — only appear to have purpose and value when viewed in connection with, or rather as subsidiary to .... the great stream of Anglo-Saxon emigration to the west.”

Obscure as is the problem of the advance of civilisation, we can at least see that a nation which produced during a lengthened period the greatest number of highly intellectual, energetic, brave, patriotic, and benevolent men, would generally prevail over less favoured nations (Darwin 1871:179-180).

This serves as introduction to a section about the means by which natural selection led to the origin of mankind from animals, and civilized societies from barbarous ones. Darwin describes a kind of race-level or nation-level selection, using his “struggle for existence” metaphor. Then he returns to the topic of the Fuegans, upon whom he had spent such consideration in Voyage of the Beagle, to suggest they had been "compelled by other conquering hordes to settle in their inhospitable country, and they may have become in conseqeunce somewhat more degraded."

This raises a question that Darwin considers further: if people can become “degraded” as a consequence of inhabiting an “inhospitable” place, perhaps it is possible that all of the “barbarous” peoples have suffered this fate sometime in the past, explaining their current states?

He spends only a couple of paragraphs on this question, with a brief statement that “civilized” peoples carry customs that link them to barbarous peoples, referring the reader to Tylor for details. I find this interesting as a reminder that Darwin operated in parallel with the beginnings of real ethnology. The section concludes with this remark, which concerns what a cladist would call the "character polarity" of civilization:

[T]here can hardly be a doubt that the inhabitants of these many countries, which include nearly the whole civilised world, were once in a barbarous condition. To believe that man was aboriginally civilised and then suffered utter degradation in so many regions, is to take a pitiably low view of human nature. It is apparently a truer and more cheerful view that progress has been much more general than retrogression; that man has risen, though by slow and interrupted steps, from a lowly condition to the highest standard as yet attained by him in knowledge, morals, and religion (Darwin 1871:183-184).

It is one of Crosby's themes that disease itself was a factor driving formerly vibrant indigenous societies into a state of collapse just prior to European colonization. The seeds of that hypothesis are there in facts that Darwin (and others) knew. But those nineteenth-century authors had very different interpretations.

References:

Crosby AW. 1994. Germs, Seeds and Animals: Studies in Ecological History. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY.

Darwin C. 1860. The Voyage of the Beagle. Revised edition. Online free text.

Darwin C. 1871. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Vol. 1. John Murray, London.

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.