Lactase and the Neandertals

Occasionally a new study finds something very counterintuitive. Those make for the most interesting results, the ones that make you think. Last week one came across my desk: Around 25% of people in China inherited a haplotype from Neandertals that may help them to digest milk when they are adults.

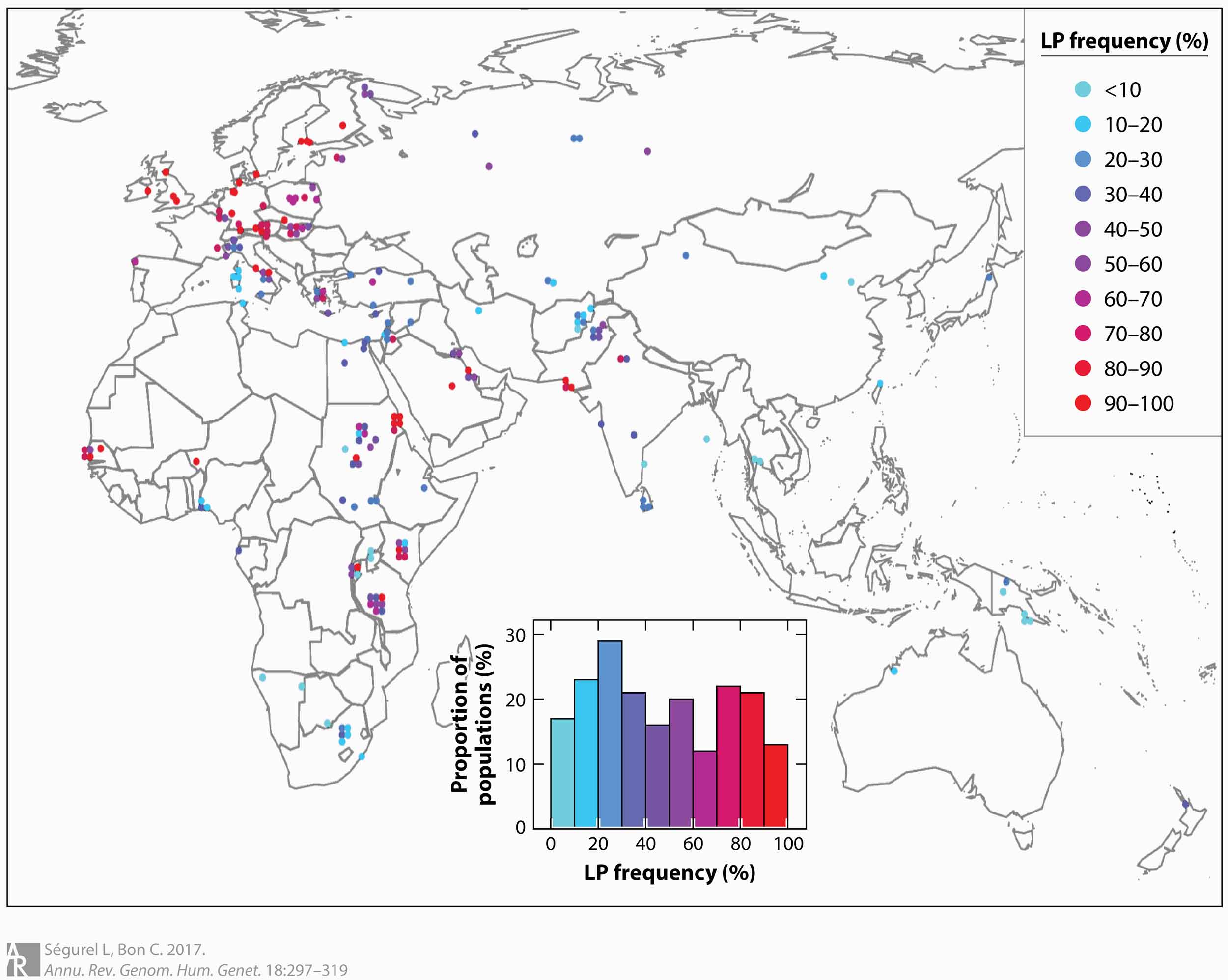

Lactase persistence—the continued production of the lactase enzyme into adulthood—is one of the best-known examples of human genetic evolution. The trait is known to be most common in northern Europe. It has a somewhat lower incidence following a gradient toward the south and east, punctuated by islands of higher frequency in several parts of Africa and in northern India and southern Pakistan. The trait is novel, not characteristic of most humans in the world before the last 10,000 years or so.

East Asia and Southeast Asia are among the many regions that do not have high frequencies of people who express lactase as adults. Still, lactase persistence is not totally absent in these places, and in some local areas includes 20% to 30% of people. What these people seem to lack is any of the genetic correlates of lactase persistence found in other populations. The genetic basis for the trait in East Asia has been a mystery.

The new research from Xixian Ma and collaborators identifies a haplotype surrounding the LCT gene that is common in today’s East Asian people. The paper shows that this haplotype was positively selected in ancient ancestors of Chinese, Japanese, and other nearby populations. Surprisingly, the haplotype originated in Neandertals. It's a fascinating genetic finding that frankly stunned me.

Lactase persistence in the textbooks

Neandertals weren't supposed to have lactase persistence alleles. When the Neandertal genome was first announced in 2010, one of the first genetic regions investigated by Svante Pääbo and collaborators was the region of chromosome 2 surrounding LCT, the gene for lactase. The reason was simple. There was a big reason to expect that Neandertals might be different from living European people in this specific part of their genomes.

Today many people of western Eurasia carry a genetic change to this region that promotes the expression of lactase in older children and adults. This genetic change, known by its position relative to the coding region of LCT as −13910*T, first began as a new mutation in one individual sometime within the last 10,000 years or so. That new allele came under strong positive selection as the domestication of dairy animals made milk more and more a part of many people’s diets. It carried with it a long surrounding block of DNA, an extended haplotype, that hitchhiked with the adaptive change toward higher and higher frequency over time in the populations where it benefited people.

After this history, the −13910*T variant is very common among living peoples of northern Europe, found at frequencies of 70% or higher in some places. With such a recent origin and high current frequency, LCT is one of the best-known examples of positive selection in humans. Lactase persistence and dairy subsistence together make a brilliant example of gene-culture coevolution: The culture of dairying created an environment where the genetic change was selected; the increase in frequency enabled populations that relied on dairy to succeed within environments where agriculture was marginal or less productive.

The −13910*T variant is not in the coding region of LCT and does not change the function of the enzyme at all. Lactase breaks down the disaccharide lactose into its component simple sugar parts, glucose and galactose. Without that breakdown, human bodies cannot make much use of the sugar lactose. All mammal infants rely on milk for their primary nutrition during their early growth and development, and lactose is the major carbohydrate component of milk, carrying energy from mother to baby. Every mammal needs to make this enzyme when they are infants relying on milk.

What the −13910*T variant is correlated with is a change in the expression of the gene. People whose two copies of chromosome 2 both have the ancestral A allele instead of the derived T allele tend to lose the expression of lactase in their guts as they grow from childhood toward adolescence and adulthood. The −13910*T is correlated with a more sustained expression of the enzyme, known as lactase persistence.

Lactase persistence is a new phenotype in humans. Most mammals don’t keep this enzyme going throughout their lives, because most mammals don’t have much—if any—access to dietary lactose after they are weaned. That has been true of most humans throughout our evolutionary history, too.

Domestication of dairy animals changed this. Whether the milk came from horses, yaks, cattle, camels, zebu, sheep, or goats, lactase is a key energy source for people who consume milk and many milk products. Before the appearance of the Neandertal genome in 2010 human geneticists knew that the haplotype including −13910*T had been strongly selected, probably in the last 10,000 years. In addition, several other haplotypes correlated with lactase persistence had been observed in other regions, including three new variants in Africa and one in southwest Asia. The data on their histories were much less clear than for the −13910*T allele, mainly because these populations were not so widely sampled as part of human genetic research. That underrepresentation is a big problem in human genetics research even today. Still, all of these variants show hints that they might have been selected also.

All this is a longwinded way of explaining why it would have been surprising to see the −13910*T allele in a Neandertal. The Neandertals lived more than 40,000 years ago. As far as we know, they never milked an aurochs. They would have had very little opportunity to consume milk or milk products after they were weaned from their own mothers’ milk.

So maybe it was a relief that the Neandertal draft genome did not have the −13910*T allele. It's exactly what most anthropologists and geneticists would have predicted back in 2010. Ancient DNA gave a slight affirmation of what had seemed true from many other kinds of observations. It was a great thing for Pääbo and his team to report, also lending a bit of confidence that the Neandertal genome was not just contamination from some recent person from northern Europe. Since 2010 that same result has been confirmed in all Neandertals with sequence data from this region. They all share the ancestral A allele at this location.

Over the succeeding fifteen years, many additional studies have built a DNA record of modern people in Europe, southwest Asia, and south Asia, especially within the last 5000 years. Those studies show the increasing frequency of the −13910*T allele in various populations. The pattern of selection has been confirmed as one of the strongest ever documented in human populations.

Lactase persistence in East Asia

Several unknowns lurk in this story, waiting to be resolved. One of those is the explanation for lactase persistence in China and East Asia more broadly. The trait is not as common in these regions as in northern Europe, yet it does occur and in some places its frequency ranges up to 30%. It might seem natural that the trait in East Asian groups might result from rare −13910*T carriers, but that is not the case. The −13910*T allele is almost unknown in China, Japan, or southeast Asia.

Ma and coworkers now have recognized a haplotype that may help to explain the occurrence of lactase persistence in these populations. Their work revealed that many people in East Asian population samples share closely related haplotypes in the region near LCT that are much closer to Neandertal genomes than to most other living people. Applying some data on gene expression, the researchers could confirm that this haplotype is associated with higher LCT expression, at least at a cellular level. This suggests that carriers of the haplotype may have greater persistence of lactase production than noncarriers. Still, it will require clinical or nutritional data collection to see how this affects people’s dietary intake.

Today this Neandertal-introgressed haplotype has frequencies of up to 20% to 25% in the sampled populations, which would mean around 35% to 45% of people carry the haplotype. It will be very interesting to discover if the haplotype has a higher frequency in East Asian people who have a more extensive history of dairying, such as Mongolian people. Ma and coworkers did investigate Tibetan people, who have higher dairy consumption, finding the haplotype frequency to be 27%.

The weirdest detail of the study is that the introgressed haplotype came under selection before 25,000 years ago in the ancestors of East Asian people. That date is far earlier than any evidence of dairy animal domestication. It’s also far earlier than the evidence of strong selection on the −13910*T allele that is most strongly associated with lactase persistence in western Eurasian populations. That selection was very strong across the time interval after 8000 years ago, and continued to be strong throughout subsequent history.

Inferring the age when selection started for a haplotype can be done by modeling based on linkage decay, and can also be done by looking directly in ancient DNA samples. Ma and coworkers show results from both approaches. In the ancient DNA samples, they use one SNP as a proxy for the haplotype. This SNP increased in frequency in ancient DNA samples from East Asia, which derive mostly from China, in the period from 8000 years ago to the present. One ancient individual out of the very small sample from 10,000 to 30,000 years ago also has the SNP, which may cloud this comparison to some extent.

Meanwhile, inference from linkage decay shows that all populations had an onset of selection for this haplotype earlier than 15,000 years ago. The inferred increase in frequency in some East Asian ancestral groups is before 30,000 years ago.

Why so old? And why Neandertals?

Ma and coworkers considered it unlikely that lactase persistence was itself the target of selection at this date. Instead, they suggest that the changes in regulation induced by this haplotype may affect other biological processes. Leveraging earlier results from genome-wide association studies, they suggest that some regulatory changes may be connected with immune system phenotypes including white cell count and neutrophil count.

That remains speculation at this point. But it's appealing speculation. The idea of a role in immunity for a Neandertal introgressed haplotype ties thematically to many other introgressed haplotypes from Neandertals and Denisovans that later came under positive selection in human groups. Under this hypothesis the effect of the haplotype on lactase expression in the gut was just a side effect of other effects on immunity. Only later did the effect on LCT happen to have a beneficial effect in people who had the opportunity to add milk or milk products to their diet.

We know that in other cases such ancient adaptations to disease sometimes proved to be useful to the Neandertals' modern human descendants. When early modern people were struck by similar pathogens as the earlier Neandertals and Denisovans, natural selection favored the remaining parts of archaic genomes that made a difference in resisting the diseases.

Over the years, other researchers have suggested that selection on LCT regulation was more about disease than milk. Recent work from Richard Evershed and collaborators is a great example. They surveyed the physical evidence for dairy production in archaeological societies, in part from milk residues adhering to ancient shards of pottery. They found that the archaeological evidence of milk adds very little understanding to the current frequency of lactase persistence or its selection in past populations. To be sure, the places where lactase persistence is most common today are places where people have consumed dairy in the past. But that doesn't quite explain why the current frequency is so much greater in some places than in others where dairy foods were also eaten just as much.

No doubt the answer is a complicated mixture of various factors. One of those factors is the extent that pathogenic gut microbes may disrupt absorption of nutrients. If lactase persistence helps to shape the gut flora in beneficial ways, then it may pay off in fitness due to lower disease or pathogen load almost as much as in energy gain from milk digestion.

Notes: Once before the era of ancient genomes, I sat with a prominent human geneticist over a pleasant dinner and had a conversation about positive selection in ancient humans. My perspective, then and now, was that human populations have been very strongly affected by natural selection over the last ten thousand years. Probably stronger and more widespread across the genome than at any time in the previous seven million years. My dinner guest did not agree.

“What about lactase?” he asked. “It’s not plausible that drinking milk made that much difference to anyone surviving. It could not have changed that fast in a few thousand years, it has to have been older and affected mainly by genetic drift.”

I was surprised as you might imagine. In the early 2000s there were many human and evolutionary geneticists who thought of natural selection as basically over in humans once modern humans arose. My dinner guest thought that sickle cell was probably a good example of selection, but otherwise there were none. My point isn't that this person was wrong—we were all wrong about many things, of course. In the 1990s I and many other scientists thought it was reasonable to conclude that lactase persistence had coevolved with dairying. But others demanded a kind of data that could not be provided by 1990s-era genomics. So much of this detail about haplotypes, SNP frequencies, and gene-phenotype associations has emerged from new work in the 2000s and 2010s.

There is quite a lot that could be added on the subject of lactase persistence—a fascinating story that has had many different tellings over the years. It has been a classic example in human evolutionary biology for more than fifty years, and for the first thirty years of that time, nobody really knew what it would have looked like in preagricultural peoples. Now we know a lot, but there are still some surprises waiting, as the current work shows.

Post updated to correct reference to the -13910*T allele. Many thanks to a reader for pointing out the typo in the original post.

References

Evershed, R. P., Davey Smith, G., Roffet-Salque, M., Timpson, A., Diekmann, Y., Lyon, M. S., Cramp, L. J. E., Casanova, E., Smyth, J., Whelton, H. L., Dunne, J., Brychova, V., Šoberl, L., Gerbault, P., Gillis, R. E., Heyd, V., Johnson, E., Kendall, I., Manning, K., … Thomas, M. G. (2022). Dairying, diseases and the evolution of lactase persistence in Europe. Nature, 608(7922), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05010-7

Ma, X., Lu, Y., Stoneking, M., & Xu, S. (2025). Neanderthal adaptive introgression shaped LCT enhancer region diversity without linking to lactase persistence in East Asian populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(11), e2404393122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2404393122

Ségurel, L., & Bon, C. (2017). On the Evolution of Lactase Persistence in Humans. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 18(Volume 18, 2017), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035340

Tishkoff, S. A., Reed, F. A., Ranciaro, A., Voight, B. F., Babbitt, C. C., Silverman, J. S., Powell, K., Mortensen, H. M., Hirbo, J. B., Osman, M., Ibrahim, M., Omar, S. A., Lema, G., Nyambo, T. B., Ghori, J., Bumpstead, S., Pritchard, J. K., Wray, G. A., & Deloukas, P. (2007). Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nature Genetics, 39(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1946