Why do some invasive species start to succeed only after a delay?

Reviewing a body of evolutionary theory that tries to understand the ultimate success of some invasions after a lag.

A biological invasion occurs when a species rapidly colonizes a new geographical area. The new area is often very far from the regions considered to be part of the species’ native range.

Well-known examples include the invasion of the southern states of the U.S. by fire ants (originally South American), zebra mussels (originally eastern European) in the Great Lakes, the dispersal of cane toads (originally South American) in Australia, and grey squirrels (originally North American) in England. I’ve written about invasive species before, focusing on the example of fire ants.

Many invasions are not instantly successful, and don’t really get going until quite a long time after a species is first introduced to a new geographical area. This is called a lag. This phenomenon may seem mysterious. Some alien species seem to cling by their fingernails at low numbers for years, before suddenly exploding into invasiveness. Crooks and Soulé (1999) examined this issue of “lag times” for invasive species. There are several reasons why such lags may occur, or be manifested in historical records. The following notes are mostly a paraphrase and summary of this book chapter, with pointers to additional and subsequent research. They delineate several reasons why biologists may detect a lag during a biological invasion.

1. The species was actually expanding, but wasn't detected in some areas.

The most obvious reason why a biologist might observe a lag time between introduction and the rapid growth of a population is that he wasn’t looking hard enough. Or, to put it more gently, the resolution of observations is not great enough to detect a positive rate of growth at low initial numbers.

In this consideration of the lag effect during invasions, it should be noted that many estimates of the time between initial invasion and subsequent population explosion may be conservative. This arises from yet another leg effect: Our lag in determining the presence of a new invasive species. It is likely that many invaders are present in low numbers for some time before they are first recorded. Such "early stage subdetectability" was suggested to occur for the medfly (Ceratitis capitata) in California, which may have been present for more than 50 years prior to its discovery in 1975 (Carey, 1996). Such lags in detection of exotics will be especially likely for small or cryptic species in undersampled habitats (108-109).

This is analogous to the problem of detecting natural selection on a rare allele. It just hasn’t grown enough to make it obvious that any shifts in numbers aren’t merely random fluctuations.

Needless to say, if the sampling scheme excludes large areas and provides diagnostic samples at intervals of thousands of years – like the archaeological record – the lag in detection of a population may be extreme.

2. The inherent lag effect.

This is discussed by Crooks and Soule (1999) from pages 109-114. In some sense, it is a null hypothesis for a lag. For mathematical reasons, a population’s numbers follow a curvilinear pattern that may appear as a lag in observational data.

The exponential growth of a population has a noticable inflection point. When the population is small, its numbers increase slowly. The equation representing growth at a constant intrinsic rate r is:

Nt = N0ert

As the population becomes common, its absolute numbers begin to grow very rapidly. Its growth may appear to accelerate or explode in numbers, even though it is actually growing at the same intrinsic rate as before.

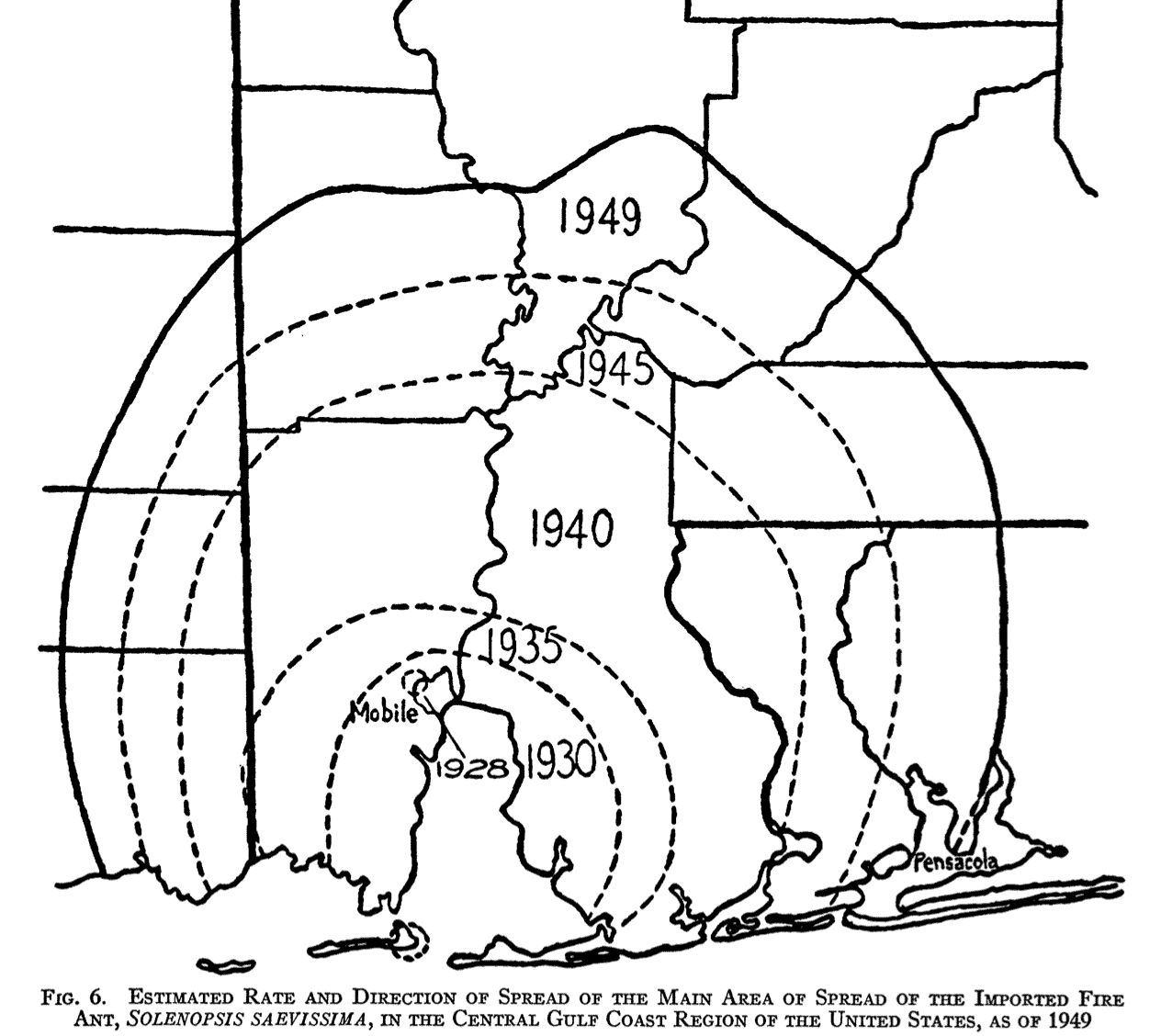

A second inherent lag involves dispersal. The most common model for dispersal of a biological invasion is a diffusion wave model, attributable to R. A. Fisher (1937) and developed further by Skellam (1951). This model predicts that a dispersing population will form a “wavefront” that moves at a linear rate over time. This means that the radius of the area occupied by a dispersing population will increase linearly with time. When a population is spreading over a two-dimensional geography, the area it occupies will increase as the square of time.

This model correponds very well to many historical cases of biological invasion. For example, fire ants:

When a population already occupies a substantial area, it becomes easy to confirm its rate of increase. But below some threshold area, this small-scale spread can be difficult to observe. Moreover, the diffusion model may break down at small population sizes. The stable wavefront really does not establish itself until a population has saturated its center of origin. Before that point, the dispersal of individuals may cover less area than predicted by the model’s linear rate of increase.

3. Environmental causes for prolonged lags.

The inherent lag effect occurs even when a population is increasing in numbers and radius at a constant rate. But the rate of increase may vary for many reasons. It is useful to consider both the intrinsic growth rate (r) and the dispersal function (D) separately, as a change in either of these may cause an apparent lag in the pattern of a biological invasion. Crooks and Soule (1999) considered these to be “prolonged” lags, in that they may be greater than expected from the mathematics of growth and dispersal in a population with constant r and D. They first discussed cases where the dispersal or growth rates may be modified by environmental changes.

In historical cases of biological invasions, human-induced changes in the environment have often enhanced the growth rate or dispersal of invasive populations. I like their example of cut-leaved teasel (pp. 105-106) because I pass a stand of teasel on the highway on my way into Madison:

The cut-leaved teasel (Dipsacus laciniatus) is a weed that arrived to New York prior to 1900, and in 1913 it was reported only from Albany (Solceki 1993). However, in the last thirty years the plant, which is capable of forming monocultures that exclude most native vegetation, has spread quickly throughout much of the midwest. This rapid spread has been attributed to dispersal via the interstate highway system, as the teasel is particularly common along highways and roads.

Obviously, providing an interstate highway of long-distance dispersal to a species with a positive growth rate is going to accelerate an invasion.

Likewise, human-induced habitat disturbance can make conditions favorable for colonizing species. This phenomenon encompasses situations as varied as the elimination of predators (e.g., coyote eradication allows red foxes to spread), fire abatement (helping red cedars spread into grassland), dams (reducing high water levels and thereby allowing canyon-bottom sandbar communities to spread) or trash dumping (creating mosquito habitat in water traps).

Climate change may play a role in some invasions. Warming trends have gotten the most attention, in that they may allow some invasive species to extend their ranges further north. But greater local importance may go to shifts in aridity or rainfall.

The final case they discussed (p. 117) is the Allee effect, a model in which a population at low density cannot find mates or utilize resources as efficiently as a denser population. As they note, this model was discussed by Lewis and Kareiva (1993) as a possible cause of lag times in biological invasions. The same topic was picked up in a 2005 review by Taylor and Hastings. Allee effects might qualify as an intrinsic lag, they are simply a case where the right population growth model is not constant growth, but density-dependent growth. But an environmental change may relax an Allee effect; likewise a genetic change in the invasive population may make it more capable of persisting at low density and thereby overcoming the Allee dynamics.

4. Genetic causes for prolonged lags.

To my mind, the most interesting cases entail actual evolution of the invading population to increase its ability to invade. Crooks and Soulé (117) provided a background to this topic, drawing heavily from the literature on colonizing species from the mid-1960’s:

The possibility of a lack of a genetic "fit" of a colonizing population to cause prolonged lags was widely speculated upon at a conference on the genetics of colonizing species (Baker and Stebbins, 1965). Fraser (1965) discussed situations where "migrants move into an environment to which they are not specifically adapted" and "will have an initial phase during which the specific adaptations will have to evolve". Lewontin (in Mayr, 1965) also discussed this issue of break-out colonizations, where under continuous identical selection, there is a long period of stalling of increase in fitness followed by a rapidly rise. Similarly Mayr (1965) suggested that the sudden spreading of the Serin Finch and Collared Dove may be caused by genetic mutation. Baker (in Mayr, 1965; Baker, 1965) commented that the sudden explosive spread of animals after a period when nothing very much seems to be happening is paralleled by plants, that if a newly introduced plant does not have appropriate `general-purpose' genotypes available, it may be confined to a restricted area until these do become available through recombination or introgression.

In 1999, Crooks and Soulé noted that there were essentially no empirical cases where such genetic adaptation had been shown important for an invading population. It made great evolutionary sense, the problem was that genetic changes were extremely hard to demonstrate (118).

Most mutations that are likely to contribute to fitness are subtle, quantitative changes in the phenotype, rather than qualitative, "Mendelian", phenotypic alterations. But the chances of researchers stumbling on such beneficial new mutations by random search are virtually nil.

This situation changed markedly during the last decade. By 2002, Carol Lee could compile a short review paper outlining cases of biological evolution accompanying invasion. Many invasive species have undergone Whether such changes were necessary to explain lag times was not clear.

More obvious was the importance of genetic variation, in Darwin’s sense, as a prerequisite for adaptation to occur. A new colonizing species, starting at low numbers, is likely to lack variation (118-119):

[P]opulation genetics theory provides some insight into the interplay between population size and genetic evolution. First, because of founder effects (Mayr, 1963) very small populations (less than 50 individuals or so) are unlikely to be able to evolve improvements in fitness (Franklin, 1980; Soulé, 1980).

Calculations based on balancing total mutation rates with genetic drift suggest that until the population size increases to about one thousand, natural selection will not be a very effective force in counteracting the randomizing effects of genetic drift ... and most beneficial mutations, even if they occur, will have a low probability of being incorporated into the population (Soulé, 1980).

Crooks and Soulé concluded that a positive feedback is likely to exist between population size and invasiveness. One way that this might affect an invading population is that new adaptive variation will appear in proportion to its expanding numbers. Hence, the invasiveness of the population may actually increase over time as its numbers increase. That would make the inflection point of explosive growth relatively steeper, compared to the case where no new adaptive variation were possible.

A small population becomes more and more likely, as time goes by, to develop the variations that makes it invasive. This would tend to enhance the lag time effect – a population truly hanging on at low numbers, until the critical adaptive changes happen to enable it to spread widely.

The importance of genetic diversity to the invasiveness of exotic species has since been demonstrated clearly in several empirical cases. Maybe the most well-known was described by Kolbe and colleagues (2004) Kolbe:2004, who studied a species of Cuban lizards that had been introduced in Florida and throughout the Caribbean. The invasive populations were cases where recurrent introductions had brought genetic variation from Cuba or other sources into small founder populations.

Why lags are important

I don’t need to say a lot about why invasion lag times are interesting; I’ll revisit this issue later. But one aspect that resonates for biologists (120):

Recognition of both inherent and prolonged lags suggest that the past performance of an invasive species may be a poor predictor of its future potential for numerical increase, range extension, and ecological effects. It is dangerous to assume that ecological containment (mal-adaptation) will last forever, especially if numbers of individuals pass the threshold that increase the likelihood of enhancements of local adaptation by natural selection.

From one way of thinking, this is no more than to conclude that natural selection is stochastic, and a new adaptive trait can appear at any time. It’s more likely to happen in a large population, and it’s more likely to happen when the population is far from an adaptive optimum.

But an alien species is more likely than natives to be far from its adaptive optimum, because it finds itself in a geographical setting far from where it evolved. It may be barely hanging on in this new location. But in the long run that’s an ominous sign – it’s the signal that the genetic background of this alien may have a lot of potential for rapid improvement.

References

Brown Jr, W. L. (1957). Centrifugal speciation. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 32(3), 247-277. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2815259

Crooks, J. A., Soulé, M. E. (1999). Lag times in population explosions of invasive species: causes and implications. In Sandlund, O. T. ed., Invasive species and biodiversity management, 24, 103-125.

Fisher, R. A. (1937). The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Annals of eugenics, 7(4), 355-369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1937.tb02153.x

Lee, C. E. (2002). Evolutionary genetics of invasive species. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 17(8), 386-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02554-5

Lewis, M. A., & Kareiva, P. (1993). Allee dynamics and the spread of invading organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43(2), 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007

Skellam, J. G. (1951). Random dispersal in theoretical populations. Biometrika, 38(1/2), 196-218. https://doi.org/10.2307/2332328

Taylor, C. M., & Hastings, A. (2005). Allee effects in biological invasions. Ecology Letters, 8(8), 895-908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00787.x

John Hawks Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.